But to understand the universe as it really is, we need a three-dimensional picture of the skies. The Copernican revolution started this change in perspective, but it took until the 20th century for a true understanding of the universe’s scale and layout to evolve. The researcher who provided one of the biggest keys was a deaf woman who earned 30 cents an hour.

Changing Stars Unlock a Map

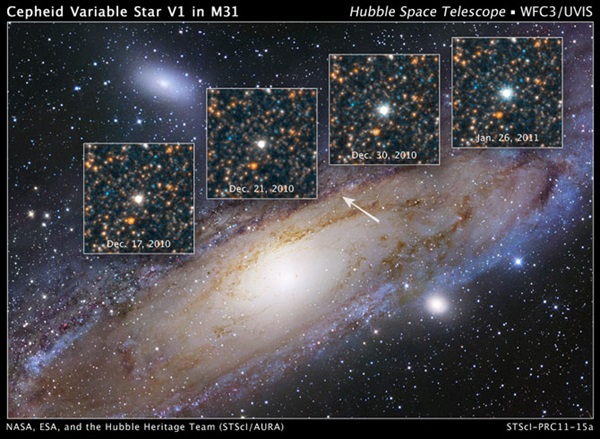

At first, this was nothing more than a curiosity. It didn’t mean anything to anyone. But Leavitt made it very meaningful with her follow-up work. She looked at a sample of variable stars that were all near the same location, in the Small Magellanic Cloud. This is a tiny dwarf galaxy very near to our own Milky Way. Here, with a smaller sample, her trend was even clearer. Brighter stars had longer periods.

It’s worth an aside here to remind readers of something you’ve certainly experienced in real life. If you shine a flashlight in a friend’s face from a foot away, they will likely ask what you’re thinking, because that flashlight is very bright. If you shine the same flashlight at their face from across a football field, they’ll be less cranky, because the flashlight will appear much less bright to them. The flashlight itself has not changed brightness, but distance has made its apparent brightness much less. Back to our story.

Leavitt realized something very important here, though it’s not clear many others did at the time. Because the stars in her second study were all in the same place, they were all essentially the same distance from Earth. So her discovery was telling her something intrinsic to the stars themselves: the longer a star took to change brightness, the brighter it actually was. So, if another star took a long time to change brightness but didn’t appear brighter, then she concluded it must be farther away, thus dimming its true brightness. With this simple relationship, Leavitt turned a two-dimensional picture of the sky into a 3D one.

Finishing the Scale

Leavitt never earned fame in her own lifetime, nor a fancy telescope namesake afterward. But when looking up at the night skies, it’s worth remembering that she is part of the reason we have a three-dimensional map of the skies, instead of the flat picture that sustained humans for so much of our history.