“There’s really not that much evidence,” says economist Alexander Whalley of the University of Calgary. He and colleague Shawn Kantor, an economic historian at Florida State University, are working on a project to measure how the space race affected jobs and economic prosperity in U.S. cities. “There’s a lot of stories kind of running around, and we’re trying to actually calculate or estimate how big are those effects,” he says.

Economic productivity in the U.S. was booming in the 1960s, according to Whalley, but growth slowed in the 1970s. This calls into question just how much of a boon the space race really was.

It’s a question that hasn’t gotten much attention from economists yet — at least not in a rigorous, quantitative way. Kantor suggests the space race wasn’t quite old enough for economic historians like himself to study until recently. “It’s just now becoming economic history,” he says.

Whalley and Kantor caution that these results are preliminary; they’re working on investigating more deeply continued from p. 77 as the project continues. But so far, their findings suggest that the space race wasn’t all good news for the job market. While companies contracted by NASA grew and hired more workers, employment in other companies seemed to drop; the researchers hypothesize that improved computing technology from space race efforts might have resulted in fewer necessary workers in other industries.

Whalley and Kantor aren’t trying to say whether or not the space race was worth it. But by measuring the effects it did have, they hope to help governments make informed decisions about when and how to invest in science and technology — and whether it’s appropriate to use economic growth as a motivation for doing so.

Regardless of what triggered the reforms, science education saw dramatic changes during this time. Before the mid-1950s, high school science education in the U.S. was focused on everyday applications like nutrition and what Rudolph calls “refrigerator physics” — the science you need to understand how appliances work. But scientists were calling for the American public to learn about what they actually do, like experimentation and data analysis.

The purpose of these educational reforms after the mid-1950s was to help the general public understand the research funded by their taxes and to garner support for scientific research as a whole, not necessarily to create more scientists and engineers, says Rudolph.

“If we just start focusing on trying to get people to do science,” Rudolph says, “we lose trying to understand what science is as a larger enterprise and as an institution in society.”

Scientific research doesn’t always have clear applications or result in economic gain right away. Societies must decide whether investing in science should always be a means to an end or whether it is a worthwhile goal in its own right.

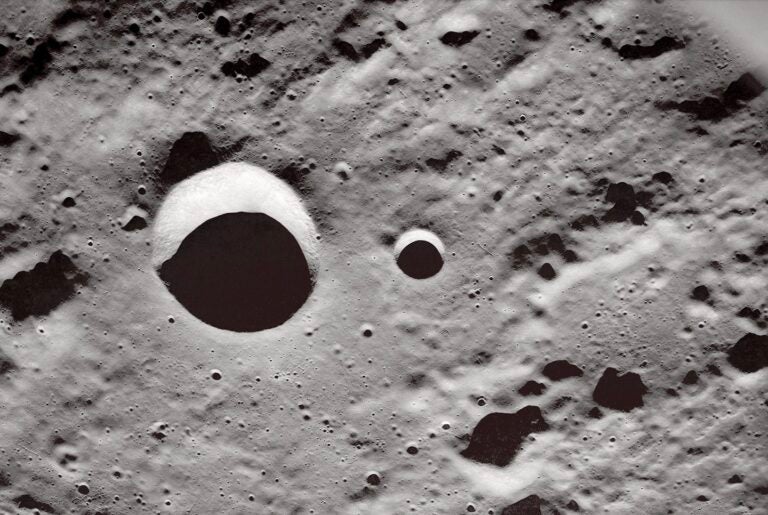

“Should we, as a society, be having another space race . . . as a way to create jobs in the future?” Whalley asks. “Or is the space race more about getting people to the Moon?”

Erika K. Carlson is a Moon-gazing science writer who dreamed of being an astronaut when she was 5.