Key Takeaways:

From Apollo through the space shuttle era, Barbara Crawford Johnson was the woman who told spacecraft how to fly. She worked on trajectories, starting with Apollo 8 and continuing through the end of the lunar program and beyond. She worked at NASA for 36 years, helping steer the Skylab space station and point the way for the shuttle program. In 1968, she was named manager of Mission Requirements and Evaluation on the Apollo program. It was the highest post held by a woman in her division. By that point, she ran a group of more than 100 engineers, mostly men, managing everything from flight test requirements to ascent orbit and descent trajectory, to overseeing resources like oxygen and batteries.

But the highlight of her career was getting to the Moon, according to an interview she gave to the Society of Women Engineers in 2003. “The whole concept of going to the Moon and landing people and bringing them back just blew my mind,” she said. “That was the greatest.”

Johnson was young when she first got accustomed to being the only woman in the room. As a child growing up in Illinois, she got a job delivering papers, and became the first ever papergirl for the St. Louis Post Dispatch. In those days, she was styling her hair like her idol, Amelia Earhart, and buying hats to imitate her distinctive style. By high school, she was spending hours watching the airplanes at a local runway and then getting taken along on rides. “Pretty soon I’d be getting to fly,” she recounted. “And then later I could taxi. … And little by little, I could fly.” She attended college at the University of Illinois, and recalled going to dances and chatting up the officers with airplanes, eventually winning rides there as well. One man she dated had his own plane that she says she learned to fly, though not without incident.

“I ran out of gas once,” Crawford admitted. “I had to land in an orchard. I sort of set it down on a tree.” She recalled a farmer and his son putting a ladder up so she could climb down, and using a crane to lift the plane out and set it on the ground again. “It was damaged, but I think the insurance took care of it.”

When she wasn’t getting stuck in trees, she took engineering classes, and became the first woman to graduate from the engineering program at her university. “I really wanted to take aeronautical (engineering),” she explained, “but at that time they didn’t have an aeronautic program. … But actually, I had fun in college. The only thing I regretted was on finals the B-12s (Navy students) had — well, they had access to all the old exams. They had files from the fraternities and things, I think. And of course, we didn’t have any in the places where I lived. I thought that was a little bit unfair.”

She had to pay her own way through college, and took a variety of jobs. “I worked as a waitress in the student union building. I counted bugs in the biology department, checked hats in the student union. I worked in a bar for about three days. I remember that’s the most money in one day because of tips. But then they found out I wasn’t twenty-one. I had a fake driver’s license — well, it wasn’t fake, it was some other person’s driver’s license. But anyway, that didn’t last long.”

By the time she graduated in 1946, she had a choice of jobs, from graduate studies and teaching, to building bridges, to an offer from North American Aviation. She took the aviation job, and never looked back.

The space program

Johnson’s work started in missiles, specifically the Navajo cruise missile. “I did the boost trajectory to start, but then I evolved into sort of handling the whole thing, the aerodynamic performance,” she explained. After the Navajo she moved on to an air-to-ground missile. And then, North American Aviation won a major contract to work on the Apollo program.

When Johnson started her career in 1946, NASA didn’t even exist as an organization. Working on missile projects, her work had largely fallen under the Air Force’s jurisdiction. The creation of NASA in 1958 was a new world opening up. She was part of the team that wrote the proposal for North American to earn the Apollo contract, and said that everyone was surprised when they actually won.

It was around this time that Johnson started moving up in her organization. “You might say I had been honchoing a bunch of people around, which I love to do anyway, but without title,” she said. “And I thought I should have a title.” She nearly moved out of her team when a supervisory role opened up in another division, even though she was eager to work on the lunar project. When she mentioned why she was leaving, her boss offered her the supervisory position on the Apollo team instead. “So, I stayed.”

Her team started out managing what was being called re-entry for the Apollo command module, as it entered Earth’s atmosphere from space. “We changed it to entry,” she said. “We reasoned that we had never exited, so we’re entering, we’re not re-entering. … We did the performance and all the design trajectories, spelled out some of the systems requirements and the environment… And little by little we expanded entry from the de-orbit, so that got us into the [rocket] boost [phase].” That in turn led to the team exploring the guidance and entry monitoring systems.

Johnson’s group developed a system that could show graphically if the guidance were working properly and the craft was coming in within safe limits. If it wasn’t, the astronauts could take over and fly. “Not accurately,” Johnson conceded, “but grossly. They would come within sort of a gross area of where the splashdown or the ship would be, using these range-to-go lines.”

She remembered it as a radical idea for its time. But, she said, “We got the astronauts into it, and they liked it.” That meant that NASA liked it, and their plan went forward.

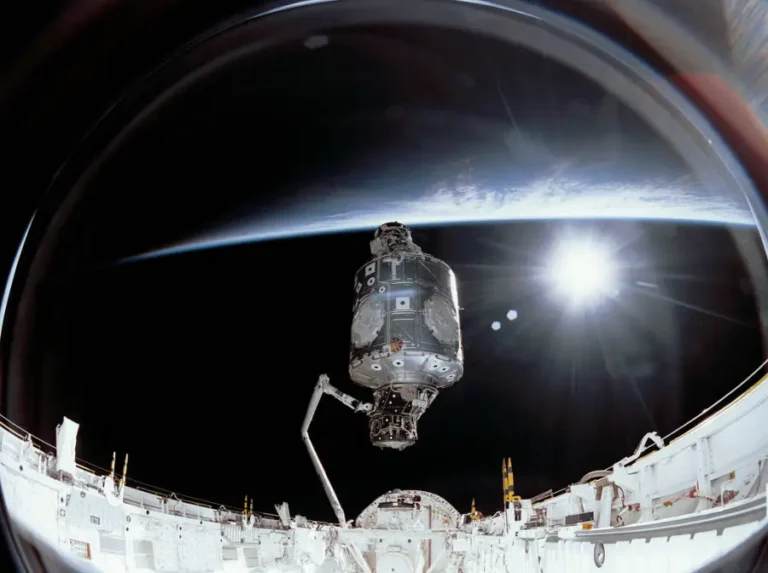

After the successes of the lunar program, Johnson shifted into work on Skylab, NASA’s first space station. Built out of hardware designed for the Apollo program, it was work she was familiar with. In fact, the crew for Skylab traveled in the same command and service module used by Apollo, so her work flowed easily from one project to the next.

The bigger shift was into the space shuttle program. Here, her rapport with the astronauts came in handy, as Fred Haise, an Apollo astronaut, was part of the team designing the shuttle requirements. “He and I coordinated — I for Rockwell and him for NASA — the requirements of the mission.” She credits their cooperation for the smooth communication between the two groups, which otherwise often argued over mission requirements. Unfortunately, Johnson suffered a series of health problems just as the first shuttle mission launched in 1981, and she retired shortly after, to watch the rest of the space program unfold from afar.

She continued to keep an interest in the space program during her retirement, and gave frequent career talks to engineering groups, schools, and even prisons. She became especially involved with the Society of Women Engineers.

After 36 years of contribution to the space program, she had her thoughts on how it should have progressed. “We should have, I thought, gone ahead and mapped the moon for future explorers. And we didn’t do that. I think that was a mistake.” She wished that NASA had pressed forward at the time with a lunar base and lunar launch facilities, instead of retiring the lunar program. Johnson died in 2005. But NASA has big plans for the moon in the coming years, hoping for a return within the next decade, this time to stay. Perhaps Johnson will finally get her wish.