Key Takeaways:

A pause in the control room, then applause ripples around. The group retires to a test cell nearby, where there are speeches and photos; a giant ribbon is cut.

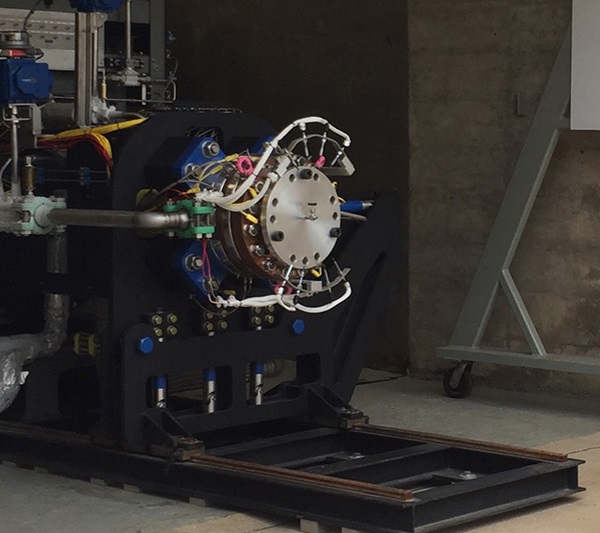

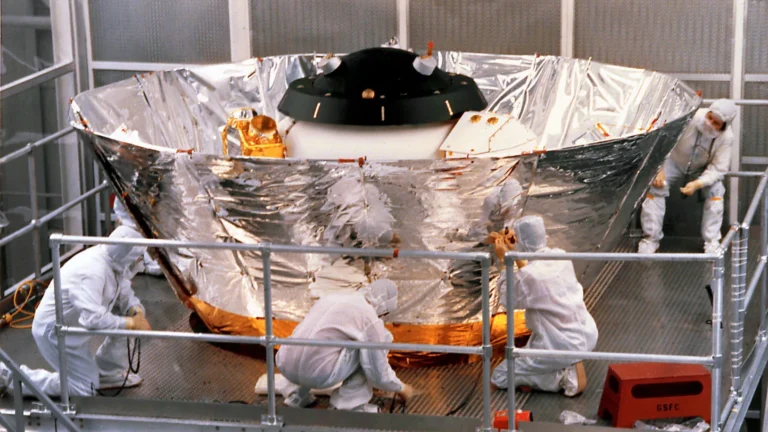

Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC) has just completed the first test of their Vortex rocket at a brand new test facility in central Wisconsin. It’s an upper stage rocket, far smaller than the behemoths SpaceX and Blue Origin use to escape the pull of Earth’s gravity, meant to help spacecraft move and maneuver once they reach space.

If all goes well, a version of this rocket will power the spacecraft SNC will begin flying to the International Space Station in 2021 for a series of resupply missions. It’s emblematic of a shift that has occurred in recent years in the aerospace industry, as new companies have begun reaching for orbit. While NASA has always relied to some extent on commercial manufacturers, the agency now has numerous options to choose from as it contemplates once again sending humans far beyond Earth.

The agency has announced partnerships with various industry players, including contracts for servicing the space station, launching satellites to orbit and building components for spacecraft. It marks a shift in how NASA pieces together larger initiatives, as the agency begins to see itself as a customer.

“We’re not owning the hardware,” said NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine at a press conference in late May, “we’re buying the service.”

Future gateway

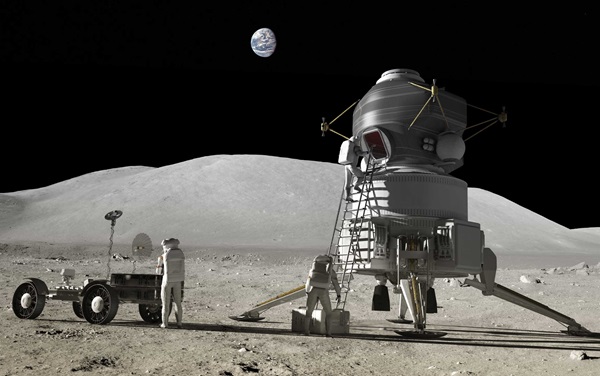

A new NASA program has many of these private companies truly excited: Artemis. Named for Apollo’s twin sister, the program is an ambitious attempt to return humans to the Moon by 2024, with the ultimate goal of building a habitat there. NASA envisions an outpost in orbit around the Moon, the Lunar Gateway, as well as a suite of spacecraft meant to enable repeat visits to the lunar surface.

It’s a tall order, and while NASA is moving quickly, it’s also relying heavily on commercial partners to develop the spacecraft and equipment that will enable a return to the Moon. On May 16, the agency announced that 11 companies would be given seed funding to conduct six-month studies of various elements of Artemis and build prototypes. A more complete call for proposals is coming early this summer, the agency said.

Just a week later, NASA announced it had chosen Maxar, a new company formed by the merger of several veteran space industry players, to build the power and propulsion element (PPE) of the Lunar Gateway. It’s the first major contract awarded for Artemis, valued at $375 million.

The PPE is based on solar-electric propulsion, a new form of engine that uses ionized atoms for thrust, powered by solar panels. The technology is far more efficient, though less powerful, than traditional chemical rocket engines — ideal for the Gateway.

That’s because NASA sees their upcoming lunar orbiter as a kind of staging point for future missions. Astronauts traveling to the lunar surface would stop first at the Gateway, where they would board a lunar lander already stationed there for their trip to the surface.

The Gateway itself would be in an orbit around the moon’s south pole, where water ice exists. Astronauts would be aiming for these ice deposits on missions to the surface, conducting research and scouting locations for a future lunar base, tentatively planned for 2028. Lunar water is a valuable commodity because it can be deconstructed into hydrogen and oxygen to be used as rocket fuel, powering future missions (including possibly as trips to Mars). Making fuel in space would be much easier than transporting it from Earth, where every kilogram of extra weight adds costs and reduces efficiency.

Small players

To accomplish such an ambitious program, NASA has reached out to multiple commercial companies to help design and build components. Some, like Boeing and SpaceX are familiar partners, but other, smaller companies, are getting the chance to win big contracts as well.

“We are really stirring the pot with industry,” says Nantel Suzuki, the program executive for NASA’s Human Landing System. “We’re asking a large group to look at an array of design challenges with multiple elements.”

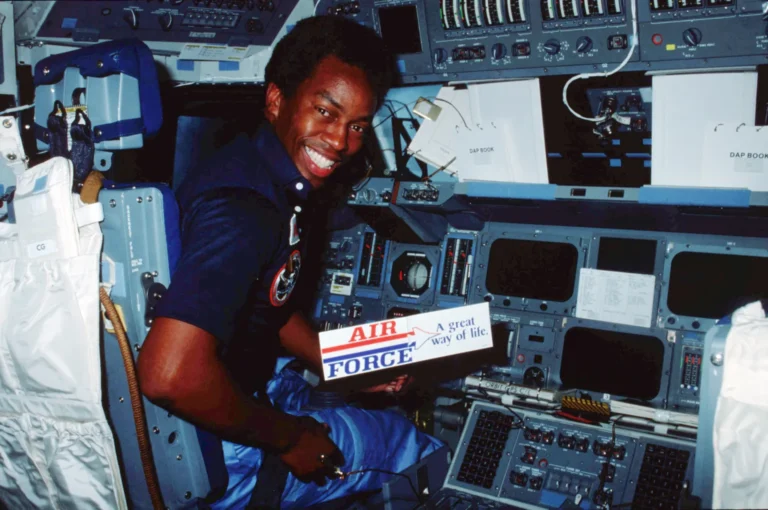

SNC is one of those smaller companies, though it’s not the first time they’ve worked with NASA. Primarily a defense contractor, SNC will fly six resupply missions to the ISS using their Dreamchaser spacecraft, an uncrewed vehicle modeled after the space shuttle. SNC is also conducting studies for the refueling, transfer and descent elements of the Artemis program, as well as building prototypes for the transfer and descent vehicles.

The studies should give NASA a better idea of what its industry partners can actually deliver, which in turn will help inform the scope of the Artemis program.

“The idea is we get the community’s overall sense of what the requirements should be,” Suzuki said.

Updating history

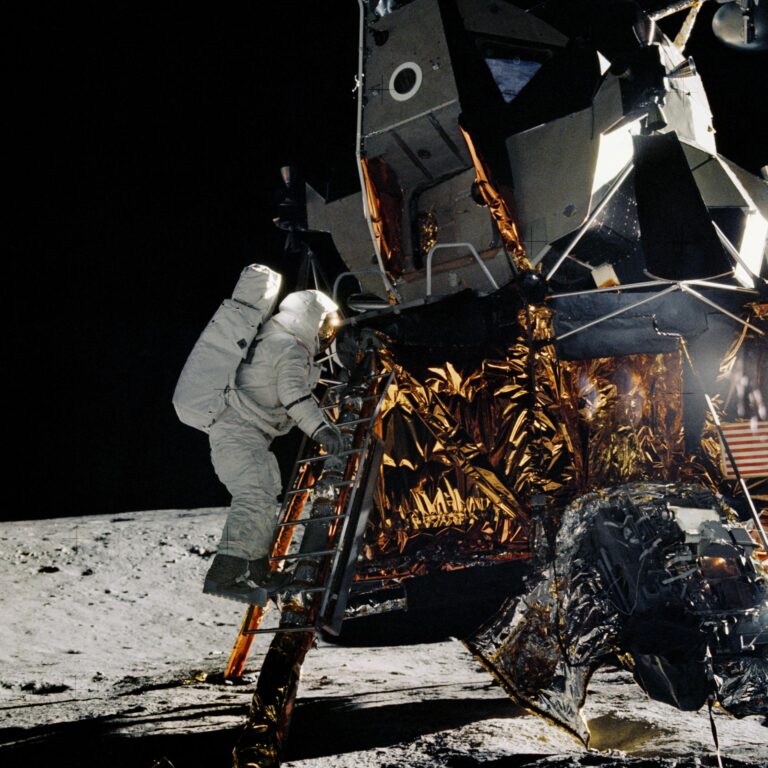

Unlike the Apollo program, Artemis won’t need to start from scratch, and most of the technology to take humans back to Moon already exists — though it may need an update.

“This was all stuff that was done 10-20 years ago,” says Paul Zamprelli, who oversees SNC’s propulsion and environmental systems. NASA has proposed plans before, in the 1990s and 2000s, for returning to the moon, though a lack of funding cut them short. “Now it’s back to the moon and all of this is fleshing back out again and we’re digging into our archives.”

And the current Artemis program wouldn’t necessarily require any technological leaps, according to Michael Elsperman, deep space architect at Boeing.

“In order to meet this really aggressive 2024 mission, there really is no new technology required,” he says. The goal instead is to use existing systems and capabilities, modified for whatever specifics NASA orders.

Many elements that Artemis calls for, in fact, were already under development through various companies.

A powerful rocket meant to launch humans and equipment for the program has been in development for the better part of this decade. That vehicle, called the Space Launch System or SLS, will put out more thrust than the Saturn V rockets that powered the Apollo program. NASA intends the rocket, and a crew capsule named Orion, to form the foundation of future missions to the Moon and Mars.

Boeing, the primary contractor for the first stage of the SLS, has repeatedly pushed back deadlines for delivering the rocket, however. Despite the holdups, the company says it can deliver the stage by the end of the year, in time to meet NASA’s goal of a 2020 uncrewed test launch of the SLS and Orion capsule.

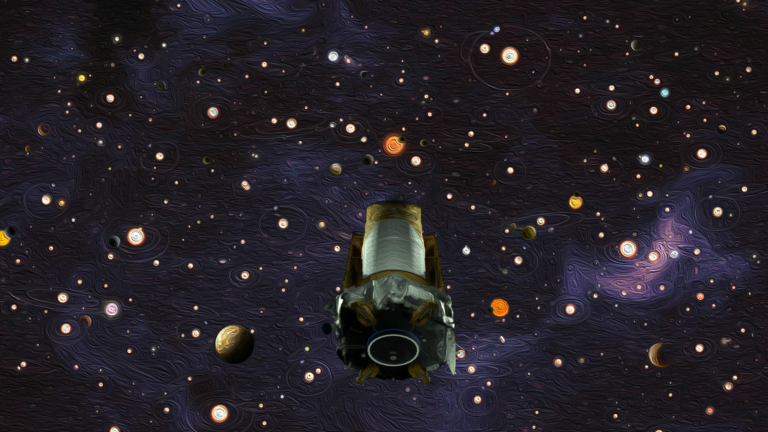

Both SpaceX and Blue Origin are working on similarly hefty launch vehicles, and a range of other companies have been developing smaller spacecraft meant to help support future NASA missions.

Masten Space Systems, which is designing a lunar descent element prototype for Artemis, has been working on a series of robotic lunar landers for years. Their Xoie craft won the 2009 Lunar Lander Challenge, and the company hopes to use similar vehicles for trips to the Moon.

The company is currently testing a small robotic lander called the XL-1 as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, and plans to deliver a small payload to the moon in 2021. A larger version of that craft could potentially bring humans to the moon as part of Artemis, says Masten CEO Sean Mahoney. Future plans for the company could include a fleet of orbital tugs used to snag payloads from orbit and bring them down to the lunar surface, he adds, or it could involve completing more robotic mission to the moon to deliver supplies or experiments.

“We have a lot of possible futures and depending on which ones come up, we’ve got a solution that fits into a whole bunch of them,” Mahoney says.

Flexible futures

That adaptability could be crucial for the new generation of space companies. NASA has moved the goalposts for its missions (or scrapped them entirely) on multiple occasions, leaving many projects floundering.

So the companies are prepared for various outcomes SNC, for example, is also building a prototype for the Lunar Gateway, as well as testing vegetable farming in space. Their VEGGIE program is housed on the ISS right now, giving the astronauts access to lettuce, tomatoes and more.

Boeing, the principal contractor for the ISS, has a full-scale model of their Gateway design, building from their experience with the space station.

And Blue Origin recently unveiled a full-fledged prototype for a lunar lander, called Blue Moon, at a press event in Washington, D.C. The lander could reach the Moon’s surface by 2024, says founder Jeff Bezos, and carry 8,000 pounds of payload. While NASA is familiar with the Blue Moon project, Suzuki says, he couldn’t confirm if the craft satisfied all NASA’s requirements yet.

Moon or bust

Ultimately, the biggest challenge Artemis poses for NASA and its commercial partners may simply be its short timescale to put humans back on the Moon. The tight timeline required a dramatic curtailing of the mission objectives: For example, the Lunar Gateway was initially proposed as a much larger, continuously inhabited station, similar to the ISS. Now, it’s likely to be used as a staging point, housing astronauts only during missions to the Moon.

The agency had initially planned to return to the Moon by 2028, but moved that date up by four years under pressure from the White House. NASA administrator Bridenstine also emphasized in his speech that the five-year timeframe was necessary in part to minimize the risk of funding being cut as a result of shifting political winds.

Perhaps as a result, the Artemis program feels more serious than previous projects meant to return humans to the Moon, said multiple sources. For one thing, the space industry has come a long way in the 15 years since NASA last proposed a lunar mission. That means the technological barriers are lower, and the options for sourcing equipment have multiplied.

“That’s one of the things that is completely different,” Mahoney says. “It’s not like we have to imagine something that is entirely and solely government-driven. We now have proof positive that it is possible to successfully meet a NASA desire, and support NASA missions, using commercial services.”

As just one example, commercial resupply missions to the ISS, by SpaceX and soon others, have opened the door to other partnerships. The possibilities are surprisingly close.

“We’ve got capabilities from commercial satellites and from [the] space station to build this gateway already there,” says Peter McGrath, Boeing’s director of global sales and marketing for human spaceflight. “If we leverage what we’ve got from those, the cost … isn’t that high.”

Instead, the greatest barrier to returning to the Moon may be the risk of funding being cut short once again.

“We can’t afford to keep starting and stopping our exploration programs,” McGrath says. “When we reset our programs every 10 years and throw away billions of dollars in investment and restart, it’s the reason we haven’t been back to the Moon in 50 years.”

But Suzuki says the agency is poised to rise to the occasion, galvanized by the tight deadline and the promise of once again setting foot on another celestial body.

“NASA’s ready to meet this challenge,” Suzuki said. “The 2024 challenge has focused the agency in a way that I’ve not seen in a long time.”