Key Takeaways:

- In 1959, NASA's initial astronaut selection, the Mercury 7, comprised solely men; however, starting in 1960, 13 female pilots, later termed the Mercury 13, privately completed and often surpassed the same strenuous qualifying examinations.

- Advanced testing for these female pilots was abruptly halted by the Naval School of Aviation Medicine due to the absence of an official NASA request, despite the program being privately funded.

- NASA's established policy requiring astronauts to be graduates of military jet test-pilot programs effectively excluded women, as they were barred from such military roles, prompting Jerrie Cobb to testify before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics in 1962 against this systemic discrimination.

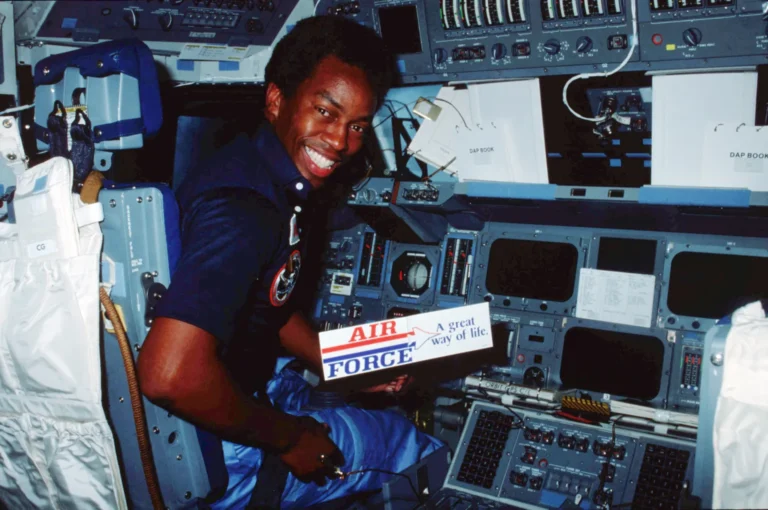

- Following the Soviet Union's launch of the first woman into space in 1963, NASA eventually sent its first female astronaut, Sally Ride, into orbit 20 years later, thereby realizing the unfulfilled aspirations of the Mercury 13.

The agency’s first team of astronauts, dubbed the Mercury 7, were selected in 1959 after passing a strenuous series of fitness and medical exams. No women were asked to participate, but a year later, William Randolph Lovelace, the doctor who had designed the qualifying exams, invited seasoned pilot Jerrie Cobb to complete the same qualifiers.

The testing was intense, including having ice water blasted into her ears to induce vertigo and a rubber tube slid down her throat to test her stomach acid. She passed with flying colors, and within a year, 12 more female pilots not only had passed, but often exceeded the test scores of the Mercury 7. Decades later, this group would be nicknamed the Mercury 13.

In 1962, she testified before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics hearing on sex discrimination, saying, “There were women on the Mayflower and on the first wagon trains west, working alongside the men to forge new trails to new vistas. We ask that opportunity in the pioneering of space.”

But NASA’s policies stood: Astronauts had to be graduates of military jet test-pilot programs, effectively barring women. Though over a thousand women had flown during World War II as part of the Women Airforce Service Pilots, they were considered civilians, and no branch of the military had subsequently allowed female pilots.