Key Takeaways:

- The Mercury program's name, chosen by Abe Silverstein in 1958, was inspired by the Roman messenger god, aligning with a pre-existing tradition of using Greco-Roman mythological names for space projects and leveraging the planet Mercury's association with space.

- Silverstein also proposed the name "Apollo" for the subsequent lunar mission. While his official biography cites the image of Apollo's sun chariot as inspiration, his obituary suggests a more pragmatic choice based on the name's appeal.

- The selection of program names involved a combination of historical precedent (using mythological figures), practical considerations (inspiring public interest and aligning with ongoing space race competition), and individual preferences of key NASA personnel.

- NASA's naming conventions for space programs demonstrate a consistent pattern of drawing inspiration from mythology, though the exact motivations and decision-making processes varied between projects.

But where did the Apollo program’s name come from in the first place? The answer is equal parts history, tradition, mythological symbolism, and sounding cool.

To be clear, there’s no master plan for all this. “Names given to spaceflight projects and programs have originated from no single source or method,” write Helen Wells, Susan Whiteley and Carrie Karegeannes in the preface to their 1976 book, Origins of NASA Names. History, folklore, and simple acronyms have also inspired the agency’s official epithets.

But Apollo and Mercury specifically were the brainchild of one man: Abe Silverstein. Trained as a mechanical engineer, he ended up working two decades at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) improving planes and jets, designing wind tunnels and fuel systems, among other things. Then, in 1958, when NACA basically turned into NASA, he helped lead the transformation, and Silverstein emerged as the space agency’s director of spaceflight development.

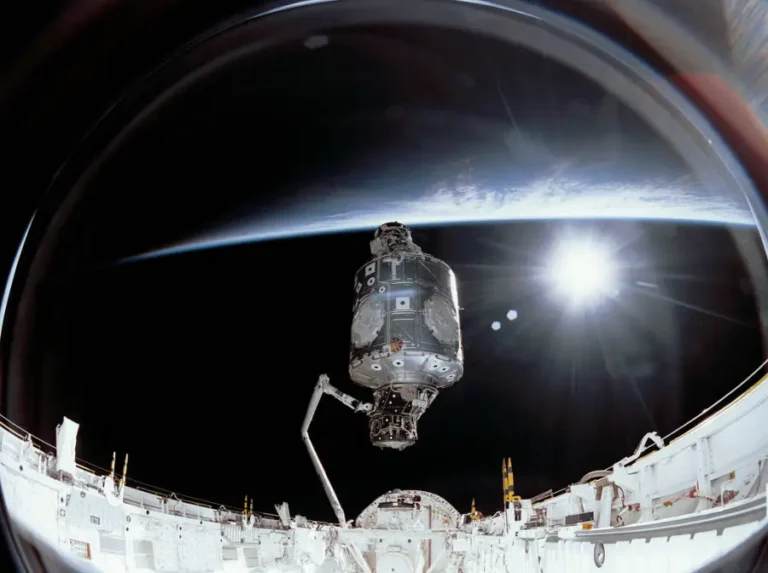

As 1958 drew to a close, the newborn agency began considering what to call its efforts. While scientific exploration was, and continues to be, a prime motivator for NASA’s activities, its formation was also largely the result of the space race that the U.S. found itself engaged in, opposite the U.S.S.R. The Soviets had already launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, the previous year; all indications were that they would soon launch a human into orbit (which they did in 1961, beating the Americans). In this competitive context, the right name, which could inspire and motivate, was key.

Robert R. Gilruth, the head of the agency’s space task group, suggested the name “Project Astronaut.” As noted in Origins of NASA Names, “The term followed the semantic tradition begun with ‘Argonauts,’ the legendary Greeks who traveled far and wide in search of the Golden Fleece, and continued with ‘aeronauts’ —pioneers of balloon flight.” But while the term “astronaut” caught on to describe the human crew members of these missions, Project Astronaut did not. “Others at NASA feared that this name would draw undue attention to the personalities of the hand-picked aviators whom NASA’s army of engineers would soon blast into space,” writes Matthew Hersch in Inventing the American Astronaut.

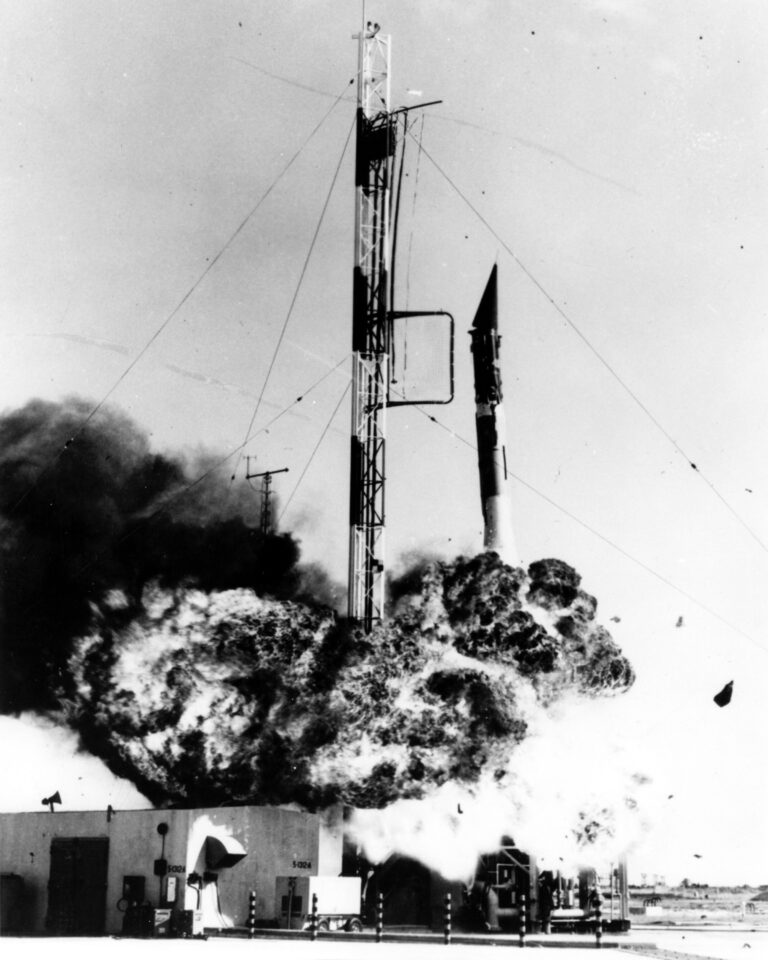

Silverstein had suggested the name “Project Mercury,” in honor of the messenger of the gods in Roman mythology. With his winged cap, winged shoes, eloquence, and ingenuity, Mercury seemed a more fitting namesake. Plus, Hersch writes, it was “a continuation of the American custom of naming rockets after characters in Greco-Roman mythology” — figures like Atlas/Centaur and Saturn. And, of course, there’s already a planet with that name, lending the word a “spacey” ring.

The powers that be all signed on with Silverstein’s suggestion, and on December 17, 1958, NASA Administrator Keith Glennan announced the name to the public. But Mercury was meant to be a first step into space, our very first crewed missions beyond the atmosphere. Soon it would be time to dream even bigger.

Apollo soars

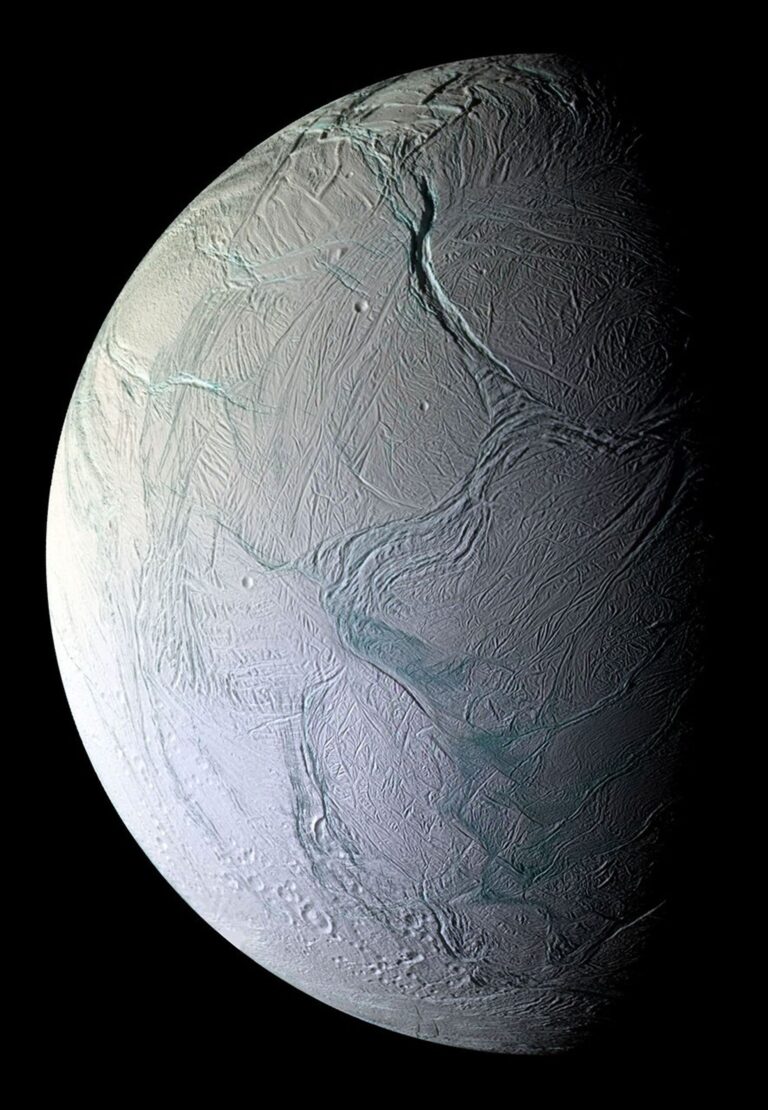

By 1960, NASA was already making longer term plans. While actually landing on the Moon was not yet on the table — President John F. Kennedy wouldn’t suggest it to congress for nearly another year, and he wouldn’t make his famous speech on the subject for almost two years — the future mission was still a big deal. It would at least reach the Moon’s orbit, and that meant launching the next great phase of human exploration.

Silverstein was again ready with a suggestion: Apollo. His NASA bio explains why: “Silverstein chose the name ‘Apollo’ after perusing a book of mythology at home one evening in 1960. He said the image of ‘Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun’ was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program.” Indeed, Apollo is the god of the Sun — a central figure in mythological astronomy — as well as the god of archery, prophecy, poetry, and music. And of course, the name follows the same convention of using mythological names he began with Project Mercury.

Or… maybe not. Silverstein’s New York Times obituary lists a far more prosaic reason for the name. “Dr. Silverstein recalled that he first dropped the name at a … brainstorming session about how to top Mercury. ‘No specific reason for it,’ he said. ‘It was just an attractive name.’”

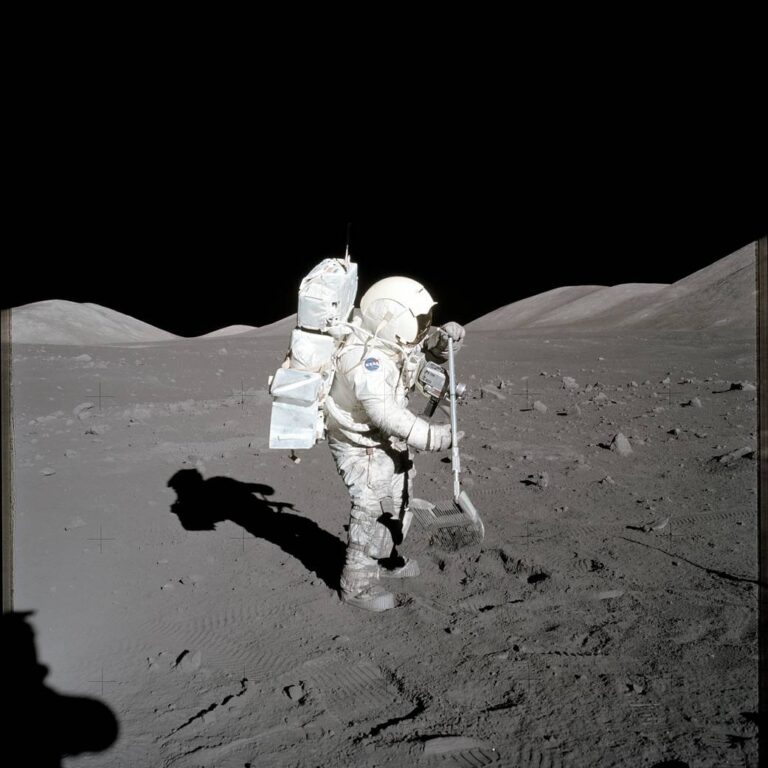

Whatever its true origins, NASA went on to approve the name and publicly announced it that summer. And of course, despite some failures and setbacks, Project Apollo was a success, and went on to land humans on the Moon for the first time on July 20, 1969.

(The Gemini program, named and developed later to figure out how to do some of the things that Apollo spacecraft needed to do, gets its name from the Latin word for “twins,” since Gemini missions had 2-person crews. It’s also the name of a constellation made up of the stars Castor and Pollux, keeping up the tradition of mythological connections.)

So Artemis has a long history preceding it, and a lot to live up to, both mythologically and technologically. But if anybody’s going to top NASA’s greatest hit, who better than the space agency itself?