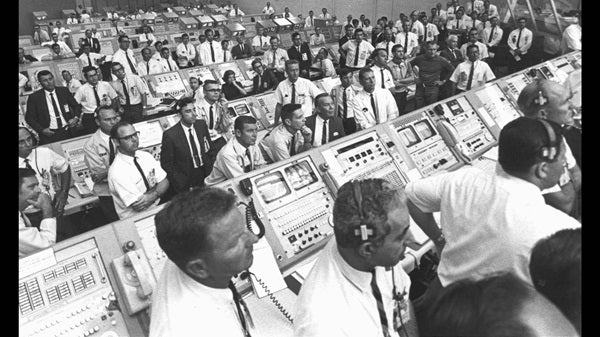

For half a century, pop culture has immortalized a group of quick-thinking, pocket-protected men as the face of NASA’s mission control room during the Apollo program. But amid this sea of men, there was one woman. Her name was Frances “Poppy” Northcutt. She calculated the return-to-Earth trajectories for Apollo 8, the first mission to leave Earth’s orbit and circle the Moon. She helped retrieve the Apollo 13 astronauts after their mid-flight disaster. And she worked on every other mission to the Moon in between.

Northcutt started her work with NASA as a “computress,” like many of the women at the space agency during her time. But unlike most women of her day, she advanced to become a member of the technical team, and ended up in mission control. After her time with Apollo, she earned her law degree and became a women’s rights advocate, and she remains a champion of women’s rights to this day. “I’ve always been involved with something that has to do with an equal state for women,” she said in a recent interview with Astronomy.

Starting at the bottom

Northcutt was born in Louisiana in 1943 and grew up in Texas. She earned her degree in mathematics from the University of Texas (now UT Austin). She went to work for a company called TRW Systems, which was a NASA contractor. Northcutt got started in 1965, when the space program was still in its Gemini days. But she quickly went to work on the future of spaceflight, flying a man to the moon, and, just as importantly, back home again to Earth.

She began her work as a computress, running calculations based on the male engineers’ work. “The computresses were all women,” Northcutt told the PBS show Makers in 2014. “All of the engineers were dudes.” These calculations were no small job in the days before machine computers became mainstream. Performing work by hand was still routine, and even using computers was a clunky affair that required reams of paper punch cards and attention to every slight detail. But Northcutt wanted to make sense of what the calculations meant, not just the numbers they spat out. “I’d take a piece of it home every night,” Northcutt told Astronomy, “and go through the code and come back the next day and start asking questions.”

Eventually, this curiosity and self-determination advanced her to a member of the technical team — essentially an engineer. But she was still a contractor and so, she says, “We were not expecting to be in the control center.” However, the Russians were beating the Americans at every step of the space race: first satellite, first man in space, first man in orbit. Feeling the pressure, NASA pushed their schedule again and again, and Northcutt found herself in the heart of the action, where communication and updates could happen more readily.

Coming back safely

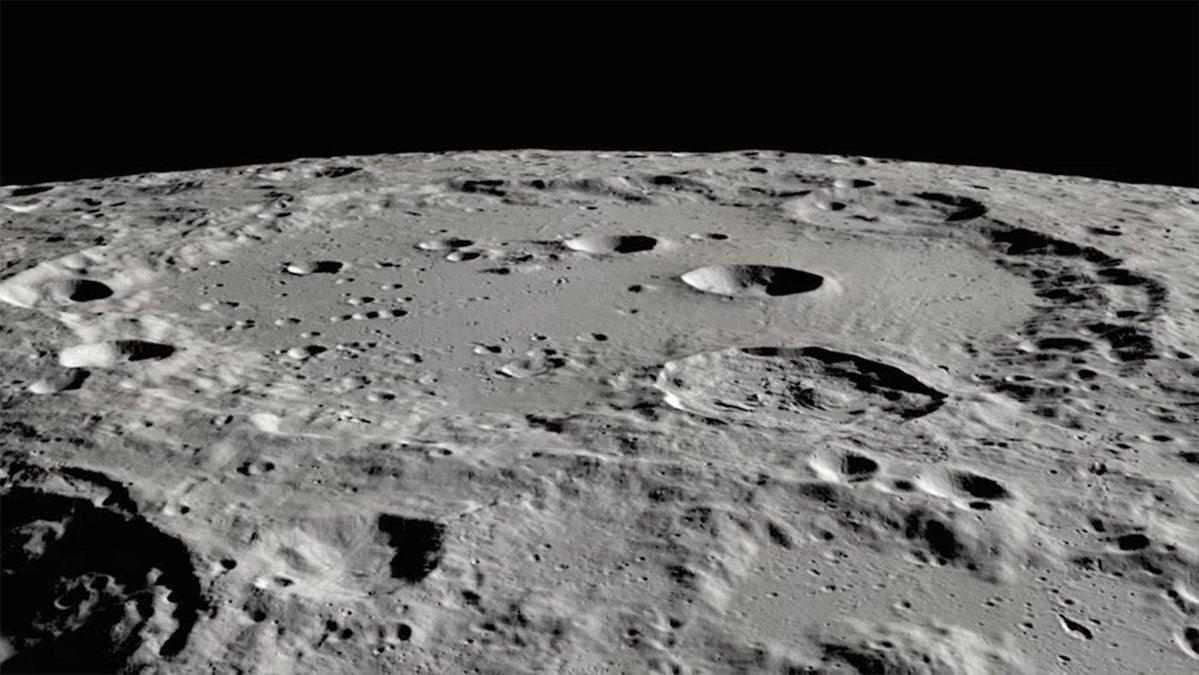

“Apollo 8 was memorable because it was the first,” Northcutt remembers. It was humanity’s first crewed mission to reach the Moon’s orbit, and the first test of much of the equipment and hardware that would be used for the later lunar missions. It was also the first test of Northcutt and her team’s calculations, which would go on to serve the later lunar missions as well. “We weren’t even really making changes after (Apollo) 8 unless something came up,” she explains.

Something did come up a year and a half later, when Apollo 13 suffered its infamous mishap. However, Northcutt says that her program was originally designed as a mission abort program. “It’s used for nominal situations as well, but it was really developed for abnormal situations,” she says. “It’s easy to come back nominally. Apollo 13 really just demonstrated that the program did exactly what it was designed to do.” While the mission revealed many problems the engineers and crew had never thought to predict, in a few ways it was the perfect example of how backup and safety systems should function. Northcutt’s program worked, and the astronauts returned home safely.

After Apollo

Northcutt remained with contractor TRW Systems for a decade, though she moved on to other projects. In 1981, she graduated from the University of Houston with her law degree. She continued working as an engineer while in school, focusing on the computers that controlled power systems in other countries. “And that was a great job to have while you’re going to law school,” Northcutt says. “Computers don’t care what you look like or what time of day you work.”

She worked for the district attorney in Houston’s Harris County, clerked for a federal appellate judge in Alabama, and eventually turned to private practice.

Much of her work has centered on women’s rights. Even from her days as a young woman with TRW Systems, Northcutt says she found ways to be involved. “I was certainly aware of the issues that were emerging,” she says of her time during Apollo. “Working in that environment I could see the discrimination against women.” And Northcutt experienced that discrimination in her own life – in her struggle to get paid what she and her supervisor felt she was worth. While she quickly earned her title as a member of the technical staff, earning an equal salary took longer. Because of her lowly start as a computress, reaching the salary level of her technical staff fellows meant leaps in pay that the company was loathe to hand out. So even with raises, she worked below the pay of her fellow engineers for a long time, even though her supervisor advocated fiercely on her behalf. “And I was very fortunate. Most women did not have someone that would fight that hard for them,” Northcutt told Astronomy. “That’s the problem that women in particular face, if they are hired at less than they’re worth. It you don’t start out equal, you will never catch up.

“So I was very aware of that. And I was also aware that I was really lucky. … And I thought, because I was lucky, that I was in a better position to be out there talking about these kinds of issues for women who were not as lucky as me.”

Northcutt also points out that the women’s liberation movement was rising across the country during the 1960s. She became a member of NOW, the National Organization for Women, advocating for equal pay, rights, and access for women. She was the first felony prosecutor in the domestic violence unit at the DA’s office where she worked. These days, her advocacy is focused on reproductive justice.

And while Northcutt may have been the first woman to work in mission control, she’s happy not to be the last. “They now have a lot of women in the control room,” she enthuses. “At (the Jet Propulsion Laboratory), a lot of the project managers are women, and on the International Space Station … It’s really exciting to see.”