Key Takeaways:

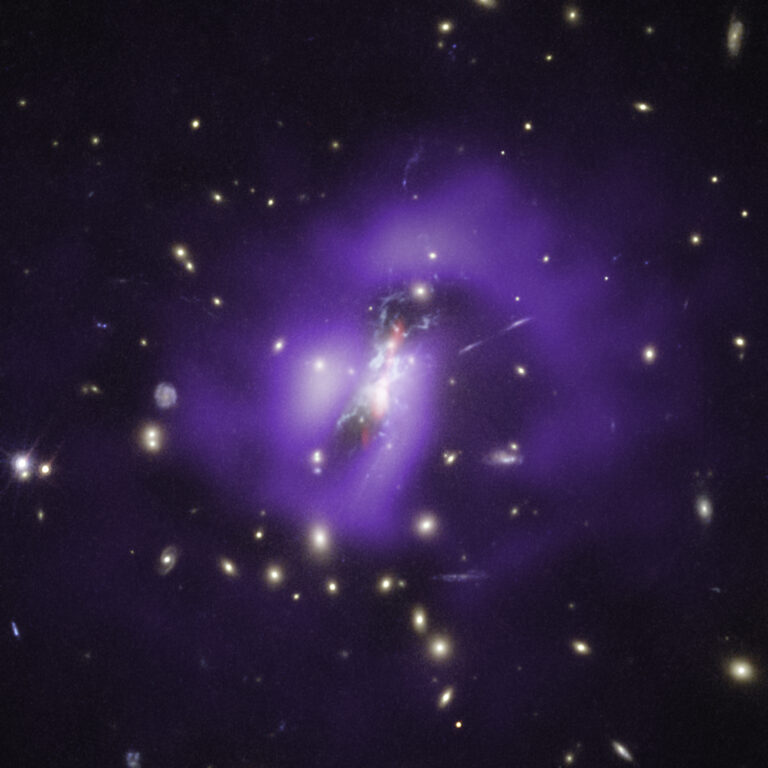

Thirteen billion years ago, two galaxies collided to make something totally new. Each of those galaxies was among the universe’s first, since the cosmic clock had only been ticking for less than a billion years. As the galaxies’ dust and gas swirled together, new generations of stars were born, and their light began racing across the cosmos until it collided with the 66 radio telescopes that make up the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

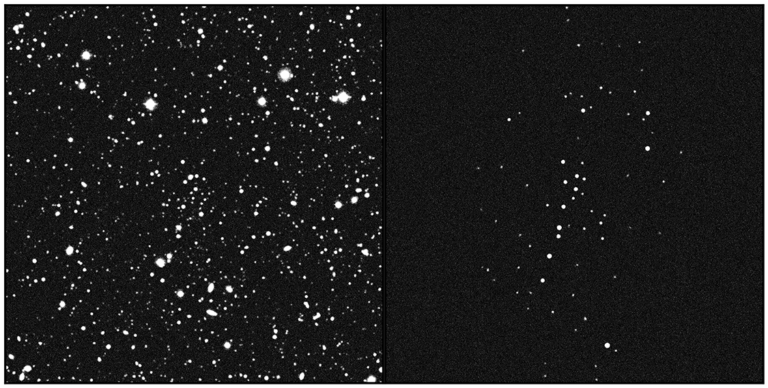

The pair of galaxies, known as B14-65666, were previously observed by the Hubble Space Telescope as two blobs of stars. But ALMA’s radio gaze also revealed dust clouds, oxygen, and carbon in the galaxies, suggesting the two are actually one system moving at different speeds. This means the galaxies are almost certainly merging with each other. Due to the mixing of the two galaxies’ materials, the new galactic offspring is producing a burst of new stars, forming baby suns at a rate about 100 times that of the Milky Way. It’s the earliest known example of merging galaxies yet discovered.

Researchers led by Takuya Hashimoto from Waseda University published their results on June 18 in Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan.

First found

Researchers think galaxy mergers are the standard way for galaxies to evolve. In fact, our own Milky Way has experienced many collisions in its past, both big and small. It’s also famously on track to collide with an even bigger galaxy, Andromeda, in the next four or five billion years.

When galaxies collide, the immense distances between stars means they usually sail right past one another. But galaxies are also made of immense clouds of gas and dust, and those clouds do mix together, roiling in new currents and eddies. As those clouds condense, they give rise to entire nurseries of star formation, with thousands of stars being born at nearly the same time.

And as those bright young stars turn on, they release a torrent of radiation, lighting up not only themselves, but also the remaining gas and dust around them. It’s these signals that ALMA picked up from B14-65666, some 13 billion years later.

Scientists have often studied galaxies colliding in the not-so-distant universe. But modern galaxies aren’t exactly the same as the cosmos’ first few generations of galaxies, which were made of nearly pristine material left over from the Big Bang. These early galaxies did not yet have time for multiple generations of stars to live and die, create new elements, and spew the elements outward via supernovae explosions.

Scientists hope that B14-65666 can teach them more about what these early galaxies were like, and how they evolved to eventually form the galaxies we see around us today.