Key Takeaways:

Titan is the only solar system moon with an extensive atmosphere and standing bodies of liquid on its surface. The moon is also filled with organic materials, and is thought to be similar to what early Earth might have looked like, before life formed, but with many of the same ingredients. Despite being a distant moon, it often ranks as one of the most Earth-like worlds in the solar system.

Dragonfly, which will launch in 2026 and land on Titan in 2034, is being managed by Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. It will be able to make multiple autonomous flights, up to a few dozen, powered by its rotors across Titan’s surface. In total, it will spend about two and a half years exploring Titan’s geology and chemistry. This includes flying over one hundred miles and searching for the possibility of life, in the past or even in the present day.

The Spacecraft

Dragonfly weighs nearly a thousand pounds, and is roughly the size of a dune buggy. Thanks to the thick cover of Titan’s atmosphere and its distance from the sun, Dragonfly can’t rely on solar power, and will instead carry a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), a nuclear power source like the one the Curiosity rover uses on Mars.

Dragonfly will carry multiple cameras to take pictures on its journey, both from a distance and up close when it lands, to get a zoomed-in image of the material it studies. It also carries a mass spectrometer, allowing it to analyze in detail the materials it encounters across Titan’s surface and determine their chemical makeup. It can perform meteorological studies as it cruises Titan’s atmosphere, and seismic studies to examine Titan’s underground.

The drone will first land in Titan’s sand dunes near the equatorial region. It has no wheels, but it can make short hops of only a few feet if it spies something interesting nearby. But it’s also designed to fly up to eight or nine miles at a time, traveling long distances to explore many different areas of Titan.

Its eventual goal is Selk Crater. Researchers are especially interested in this impact crater because of the combination of past liquid water, organic materials, and energy. These are seen as the three crucial ingredients for life. Curt Niebur, the lead program scientists for NASA’s New Frontiers program, explained during the press event that this makes Selk Crater an excellent proxy for ancient Earth, and what it might have looked like before life arose. “We can’t go back in time…” Niebur said, “But we can go to Titan.”

The Destination

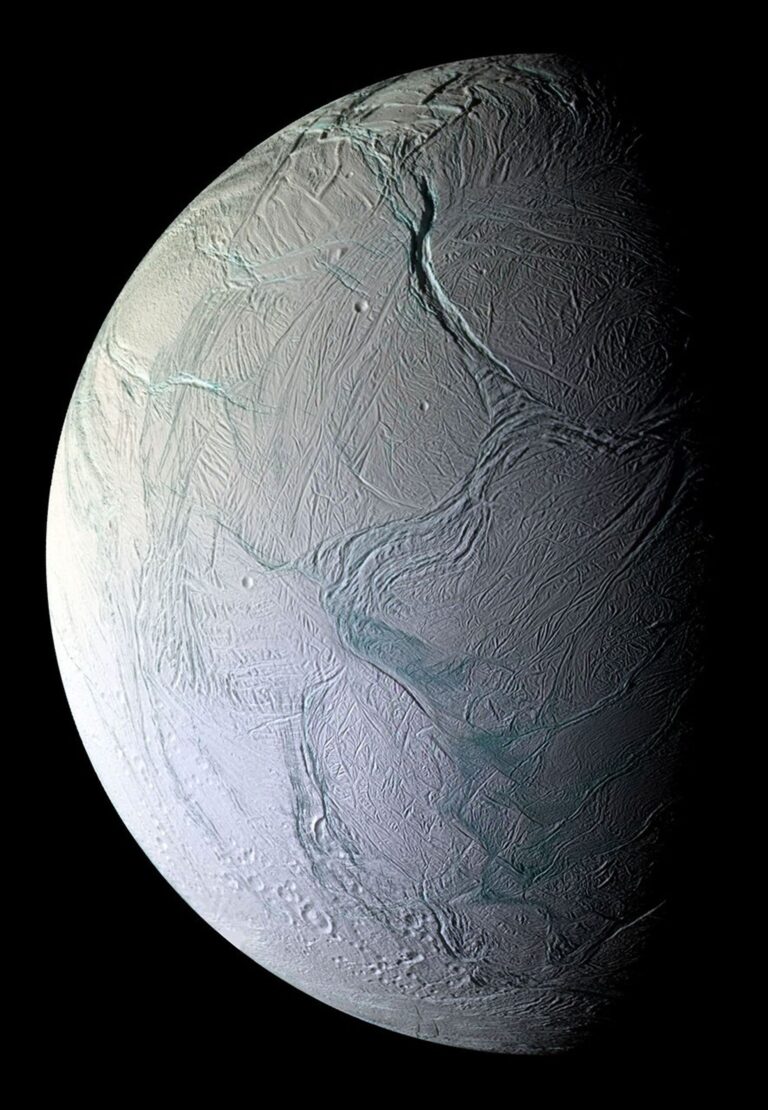

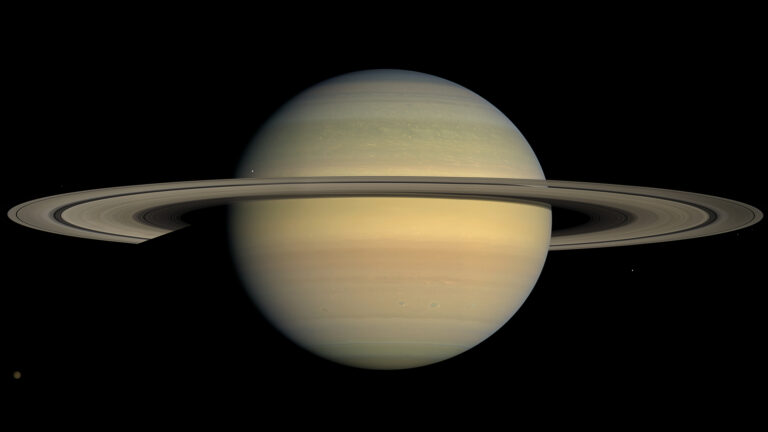

When the Huygens probe landed on Titan in 2005, researchers had no idea what to expect. Huygens revealed a complex world, covered in lakes of methane and ethane, filled with sandy dunes of organic materials, and with a complete methane cycle, analogous to Earth’s water cycle. Meanwhile, the Cassini spacecraft kept watch from its orbit around Saturn for more than a decade, eventually learning to map Titan’s surface in great detail. It was able to reveal Titan’s lakes and seas growing and shrinking with the seasons. These rich details had scientists hungering for a dedicated Titan mission, which Dragonfly will now fulfill.

Dragonfly’s full mission will last almost two years. Because of Titan’s slow movements, a full day on Titan lasts roughly 16 Earth days. Dragonfly will spend its 8-day “days” flying, communicating, and performing science tasks, and its 8-day “nights” recharging its batteries. It will perform most of its science from the ground, where it can directly access samples of Titan’s surface and run them through its on-site laboratory.

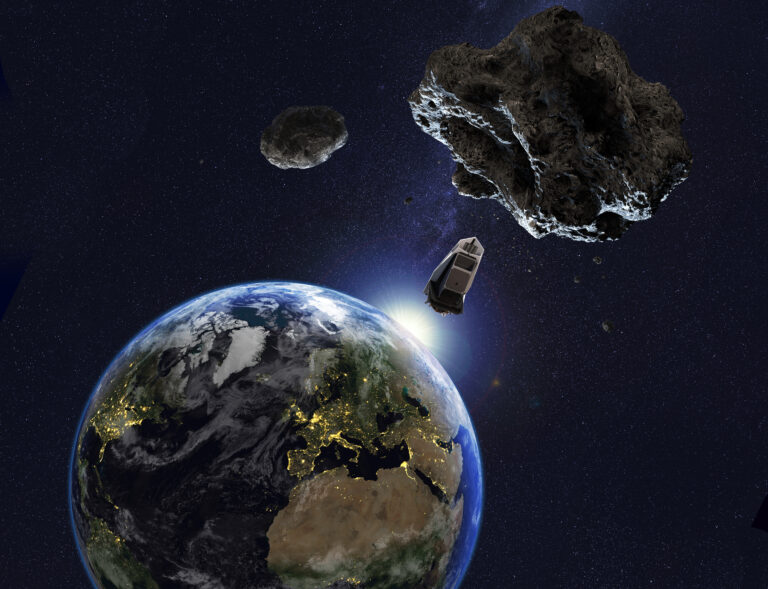

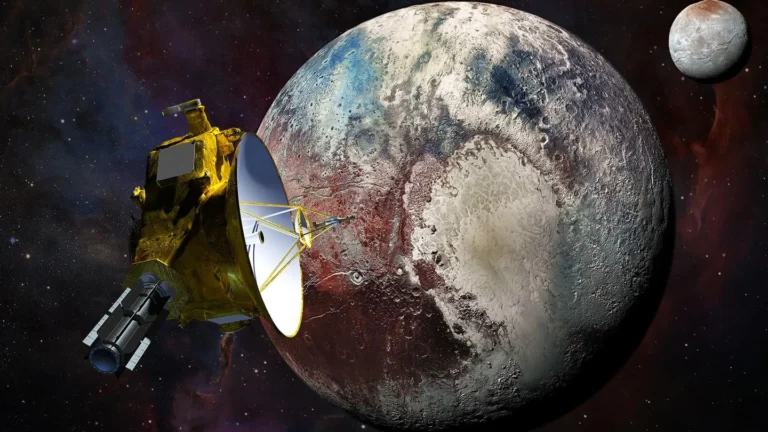

Dragonfly is part of NASA’s New Frontiers program, which is responsible for the New Horizons mission to Pluto, the Juno mission currently studying Jupiter and OSIRIS-REx, which is orbiting asteroid Bennu and planning to return samples back to Earth. Researchers will have to wait more than a decade to see any results from Dragonfly, but Titan’s complex world is surely worth the wait.