Key Takeaways:

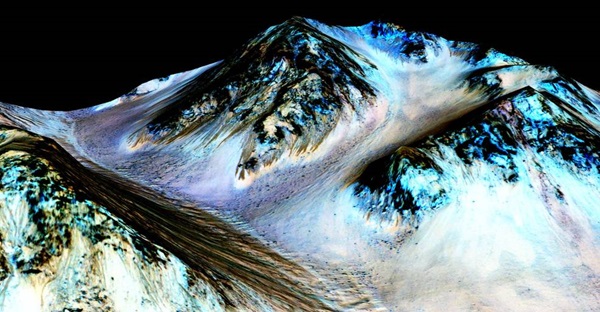

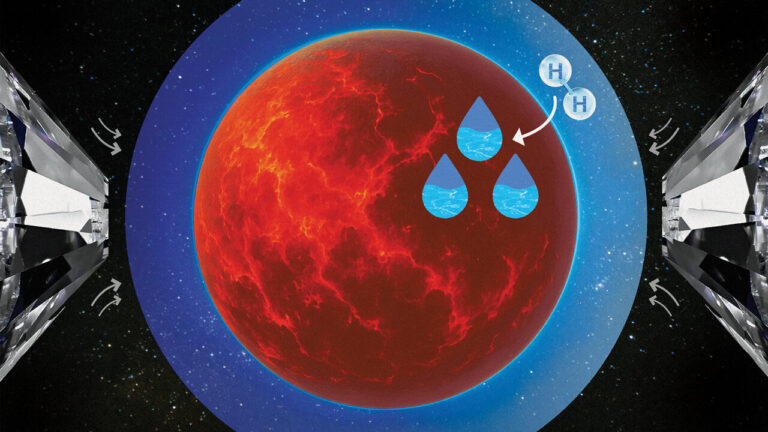

For good or ill, Mars also has vast salt deposits made of calcium sulfate, iron sulfate, and magnesium sulfate. And salts, which come in many varieties, are usually good at mixing with water to form brine: a salty liquid. In fact, in many cases, they are good at pulling water straight from the humid air to mix and form a brine.

Now, Mark Schneegurt, a biology professor at Wichita State University in Kansas, says that he’s managed to dry out and then revive bacteria under these conditions. The find means that despite Mars’ arid and salty environment, life might yet be able to thrive there. Schneegurt announced his findings at the American Society for Microbiology meeting on June 21 in San Francisco.

Salt Lovers

Most life-forms on Earth have a hard time surviving after they’re submerged in extremely salty conditions. But there are some exceptions. Scientists call these extreme life-forms halophiles (“salt-lovers” in Greek). While humans think of ocean water as relatively salty, it’s on average just 3.5 percent salt.

Schneegurt and his team harvested their bacteria from Hot Lake in Washington and the Great Salt Plains in Oklahoma. Then, they grew them in a water mixture that was a whopping 50 percent salt, enough to kill most earthly organisms.

It turns out, the organisms were perfectly happy in the mixture.

The researchers then removed tiny samples of the bacteria and dried them out. Since all organisms, even halophiles, need some amount of water to live, this effectively kills the bacteria, or at least puts it into a stasis mode, where it can’t perform any life processes (“alive” or “dead” for a single-celled organism can get surprisingly tricky).

They then locked these dried-out samples in a Mason jar containing salt and filled the jar with humidity. By simply leaving the jars alone for a day, the salt absorbed enough liquid from the humid air to form a brine, reviving the bacteria. Some of the organisms did die off during the experiment, but more than half survived and went on to grow and flourish.

The research has a double implication. For one, it implies that despite Mars’ harsh environment, Earth has already produced life-forms that can survive periods of intense dryness, then bounce back with no more than an extremely salty liquid. That bodes well for the possibility of life on Mars, either now or in the recent past.

But the other implication is a warning: If such life exists on Earth already, then researchers must be extremely careful about contamination between Earth and Mars, in both directions. NASA has an entire office of planetary protection dedicated to preserving a strict quarantine between different planets, by thoroughly decontaminating any spacecraft that has a chance of landing or impacting a planet, and rules already in place for sample return missions to Earth.

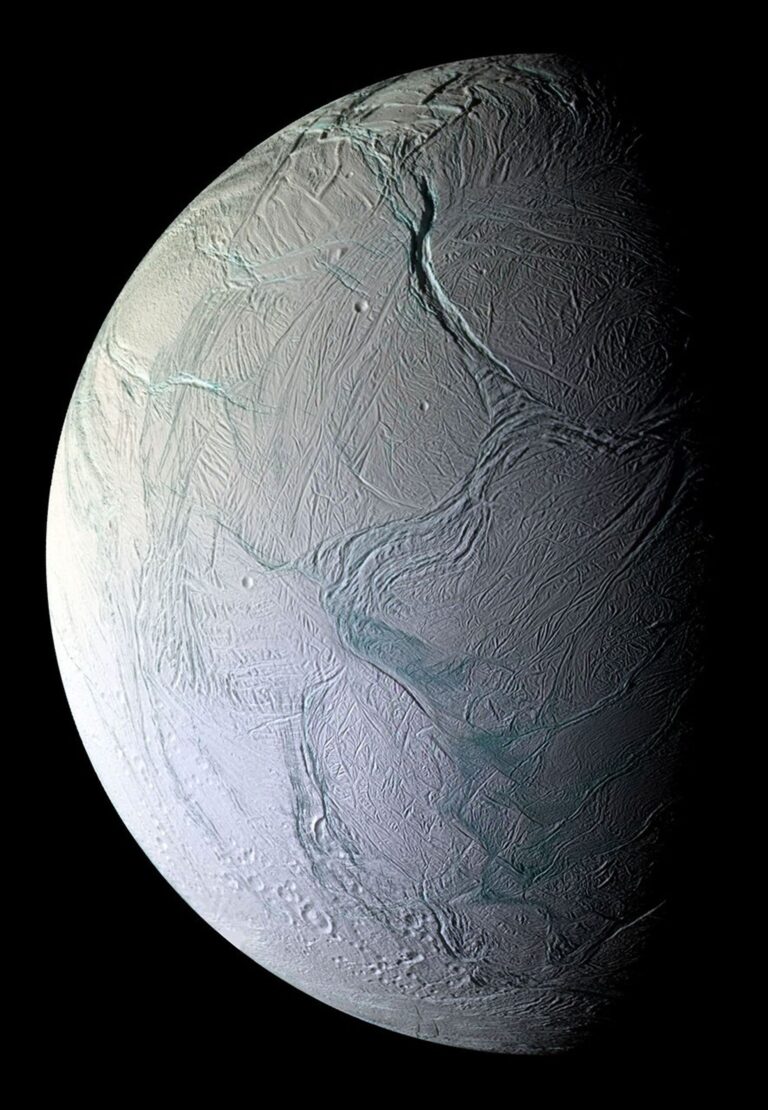

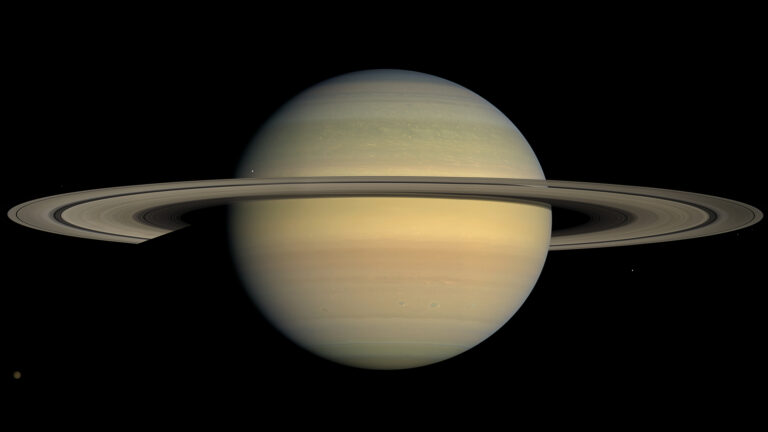

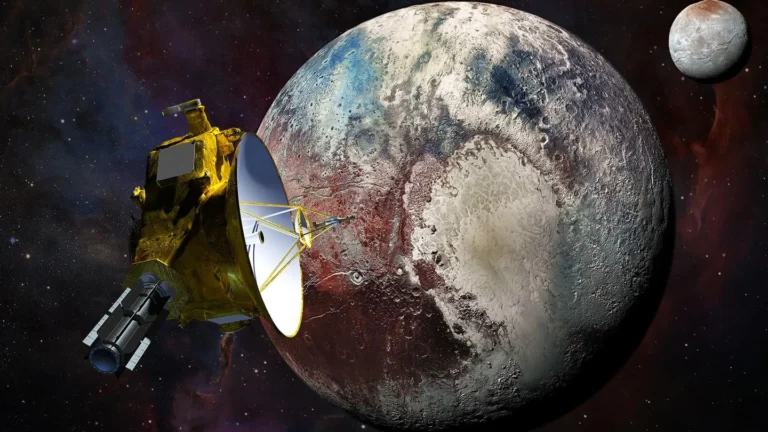

The more hardy the lifeforms scientists find, the better the chances that similar life could exist off-world, on Mars or even Europa or Titan. But it also raises the risk of such lifeforms surviving outer space and rocket launches, something scientists are already cautious about.