Key Takeaways:

But for a woman who helped program the AGC, Saydean Zeldin started off as green as any new hire. “I was a little afraid of those darn computers at the time,” she recalls from her first days on the Apollo program. And with good reason: They were a far cry from today’s touch-screen technology and natural language processing. “The first computer I programmed was in binary, if you can believe that,” she says. But Zeldin’s experience allowed her to ride the technology wave from the early days of computers during Apollo right into running a series of software companies in her later years.

A start at Apollo

Zeldin got her degree in physics from Temple University in Philadelphia. After graduating, she worked at GE’s Space Sciences Lab, investigating airflow around enemy missiles to try to identify them as they flew through the air.

When she and her husband moved to Boston for his job, Zeldin applied to work at MIT’s Instrumentation Lab (now known as Draper) when she saw an ad in the paper. “It looked like an interesting opportunity,” she says, and while she didn’t consider herself a space expert, she was a problem solver, so she went to work.

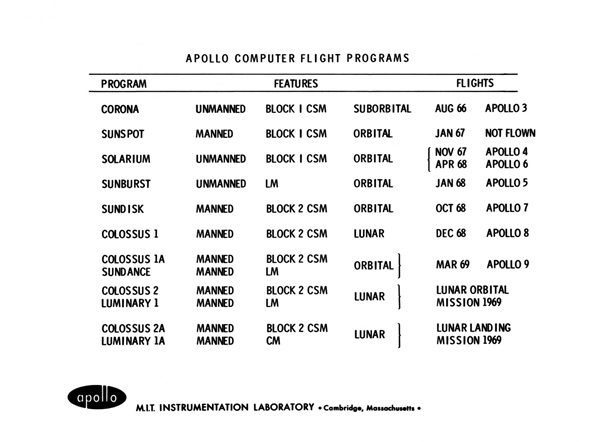

In 1966, she started working on the Apollo Command Module’s guidance system — the AGC — and eventually became section head. That meant she designed the software that allowed the astronauts to control the spacecraft engines, both during the longer portions of the trip to and from the Moon, as well as more delicate procedures such as entering lunar orbit. “I think I was the only female who worked on the application side instead of the systems side,” Zeldin reflects.

She likens her work to creating an app, whereas those working on systems side — the underlying programming for the Apollo computer system — were the ones designing the operating system. That’s where software engineers like Margaret Hamilton, famous for her stacks of paper code, made their mark.

The software changed relatively little between Apollo missions, and “I was actively involved until Apollo 13,” Zeldin says. “That was the end of the software development. It was kind of just in maintenance mode after that.”

New challenges

It was during this lull that Zeldin and Hamilton teamed up, looking for new challenges to tackle. The two women zeroed in on the process of software development. “We kept very good records during that time of all the problems that occurred during development and were trying to figure out how we could have done a better job. When we investigated it, it seemed like three-quarters of them could have been prevented if you had better techniques for developing software.”

The women set about developing those techniques, writing a series of papers together. In 1976, they started their own company called Higher Order Software, marketing their skills and making impacts on the emerging field of software development.

In 1985, Zeldin co-founded another company called Touchstone, again with another female software engineer named Cynthia Solomon. She’s better known as one of the co-developers of Logo, one of the first educational programming languages, which used turtle graphics to teach students how to program. Turtles are still popular in educational programming to this day.

Bookended by space

Zeldin retired in the early 2000s, and says she enjoys it. “All I do is collect gadgets like Alexa and things like that. I understand what it means to be a beta site customer,” she laughs. She describes her fully automated house: “I have my thermostat, my blinds, my AC. It’s not perfect, but it’s fun.”

The Apollo program was her only foray into the space sector, though the work she did on the Command Module’s computer systems certainly paved the way for later software career. She also has one last connection to space. “Fifty years later I’ll get to see my second launch,” she says. Her husband, who died four years ago, was scheduled to be launched into space June 24 by a company called Celestis, which offers space burials. “All my three daughters who went to see the first launch will be there, too.”