Key Takeaways:

- Apollo missions returned 842 pounds (382 kg) of lunar samples from six sites, comprising approximately 2,200 individual specimens collected using various tools.

- Samples ranged in age from approximately 1.2 billion years old (youngest lava flows, though no samples of this age were retrieved) to 4.4 billion years old (lunar highlands), with most being basalts, breccias, and mafic plutonic rocks.

- Analysis of lunar samples, particularly oxygen isotope ratios, revealed striking similarities to Earth rocks, supporting the Giant Impact Hypothesis for the Moon's formation via a collision with a Mars-sized body (Theia).

- The Apollo lunar samples provided unprecedented insight into lunar geology and significantly advanced the understanding of the Moon's origin.

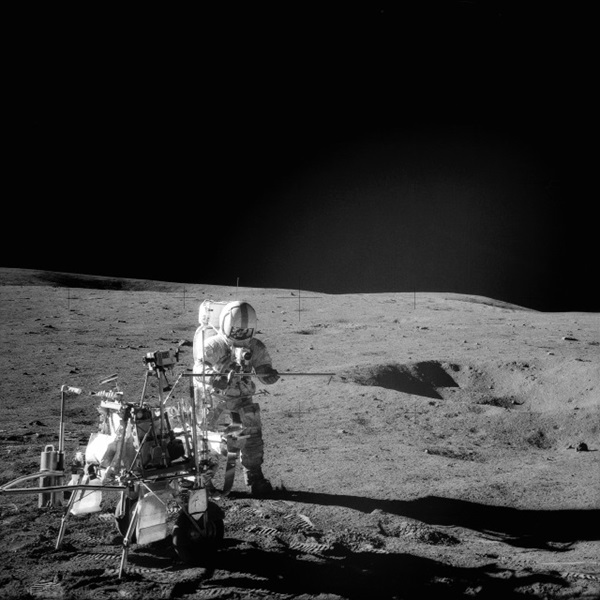

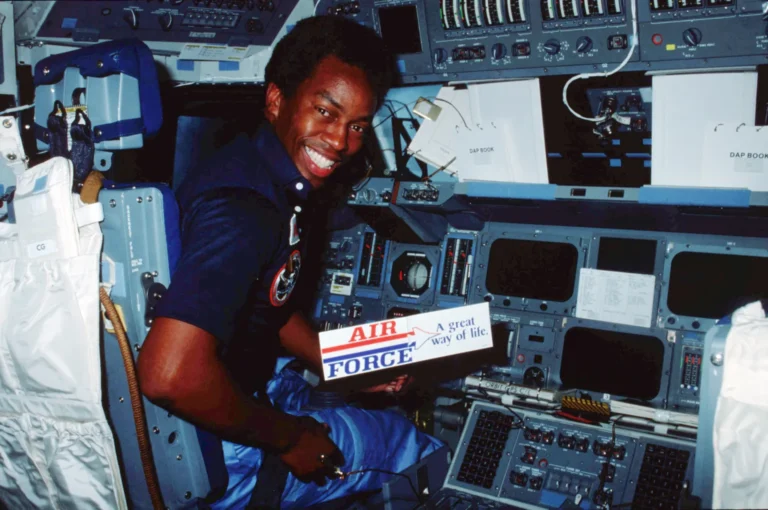

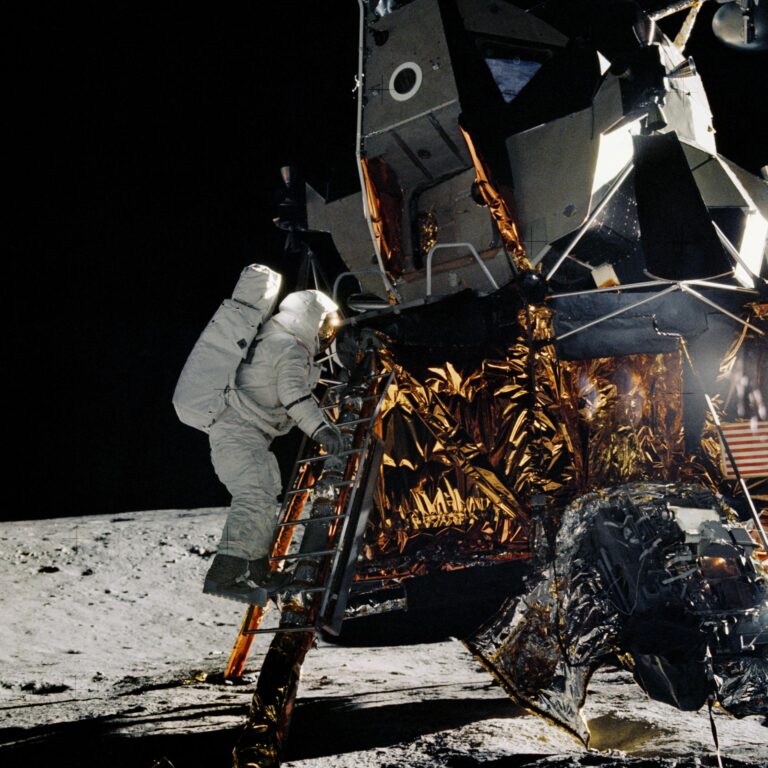

Returning lunar samples was a priority from the beginning. One of the first things Neil Armstrong did after his descent down the ladder was to pocket a specimen as the original collected piece of the Moon. The missions that followed Apollo 11 were far more aggressive, returning a wide variety of Moon rock samples, effectively opening a window into lunar geology.

From the outset, the Apollo astronauts used a variety of tools to collect their samples, including rakes, tongs, and scoops. Astronauts searched a variety of geological features, too, hoping to assemble a suite of lunar minerals and rocks of different ages.

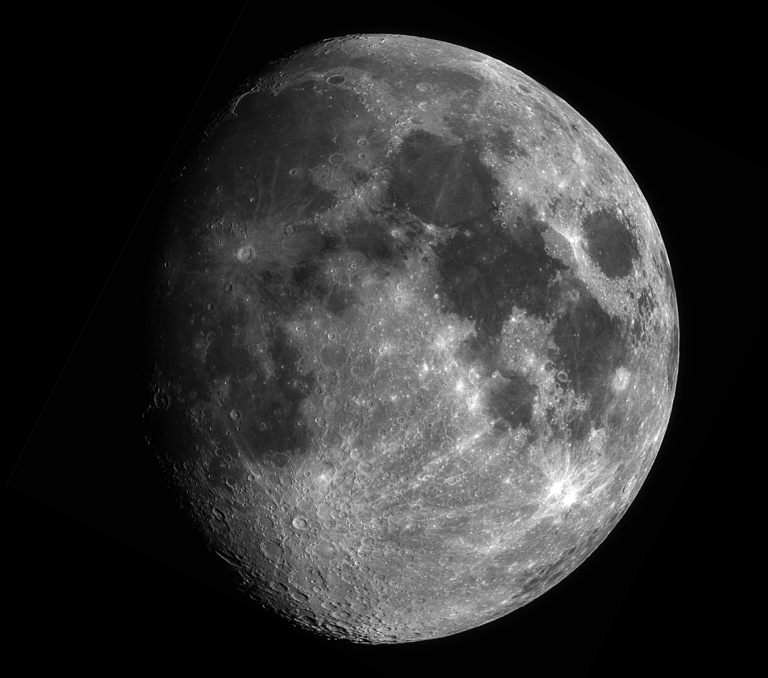

The youngest areas of the Moon are the mare, the lowlands, that filled with basaltic lava relatively late in the Moon’s formation. They typically consist of rocks that are 3.2 billion years old, whereas rocks from the older lunar highlands date to some 4.4 billion years ago. The youngest geological actions on the Moon, based on crater counts, probably were lava flows about 1.2 billion years ago. But, alas, we have no samples of these very young lunar rocks.

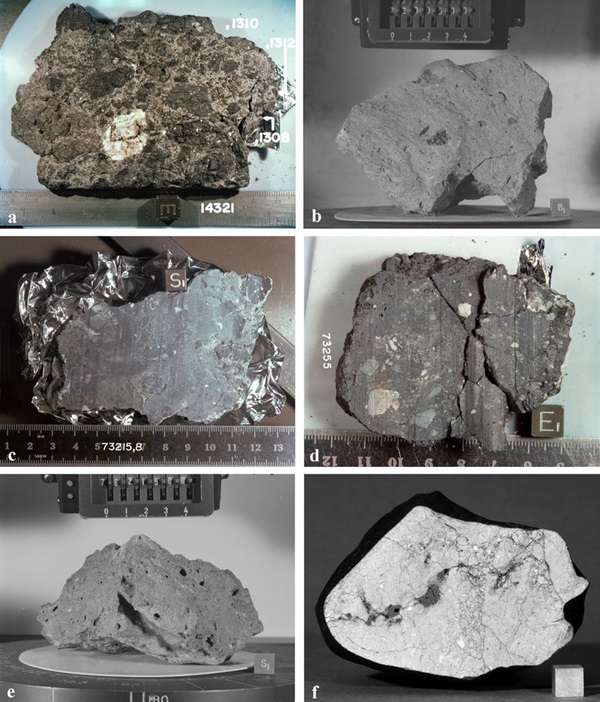

What exactly do Moon rocks look like? They are mostly grayish, and include many basalts, and breccias (rocks made up of broken and reassembled pieces), and mafic plutonic rocks from the highlands. This last type formed underground and were pushed up by the forces that created the lunar mountain ranges.

Mineralogically, most Moon rocks are pretty simple. Common lunar minerals include silicates, made up of silicon and other elements like calcium, aluminum, oxygen, magnesium, and iron. (Examples of silicates are plagioclase feldspars, pyroxenes, and olivine, the latter a mineral also commonly found in some types of meteorites.)

Along the trail of discovery, some Moon rocks have better stories than others. Genesis Rock, collected near Spur Crater by Jim Irwin and Dave Scott during Apollo 15, was originally considered extremely old because of its strange, whitish, fractured appearance. The thick rock, measuring about 3.5 inches (9 cm) across, was later determined to be 4.1 billion years old, not as old the astronauts had hoped. But the talk and analysis of Genesis Rock has made it the most famous of all lunar specimens.

Another famous rock was collected during the last mission, Apollo 17, and designated sample 70017. It is a titanium-rich basalt from the Taurus-Littrow Valley, and after an initial analysis President Richard Nixon ordered the sample sliced up and distributed to the 50 States plus 135 foreign heads of state.

After all of this effort and journey, what did the Moon rocks tell us? Ultimately, they revealed Apollo’s biggest story, the origin of the Moon itself. The most striking analytical finding showed the samples are eerily similar to Earth rocks in several ways. The signature detail was that oxygen isotopes sealed in Moon rocks — the “flavors” of oxygen atoms — matched those on Earth. This and other factors led to scientists in the 1970s proposing what came to be called the Giant Impact Hypothesis. Planetary scientists believe the Moon likely formed when a Mars-sized body, which they have named Theia, struck a newborn Earth some 4.5 billion years ago. The collision produced a ring of debris surrounding the young planet, which eventually accreted into the Moon. Much of the mass of Theia was absorbed into early Earth. This idea explains the tremendous similarities between Earth and Moon rocks.

The collection of Apollo Moon rocks returned to Earth, mostly residing in Houston, has given planetary scientists their first detailed look at the geology of another world. As a result, they have a pretty good idea of how the Moon came to be. Thankfully, we can study lunar science in the peaceful current age, only imaging what a violent and dangerous place the early solar system was.

For much more on the Apollo missions, make sure to check our special Celebrating 50 years of Apollo webpage, where you’ll find everything you want to know about the equipment, plans, and people that made the Apollo missions possible.