Key Takeaways:

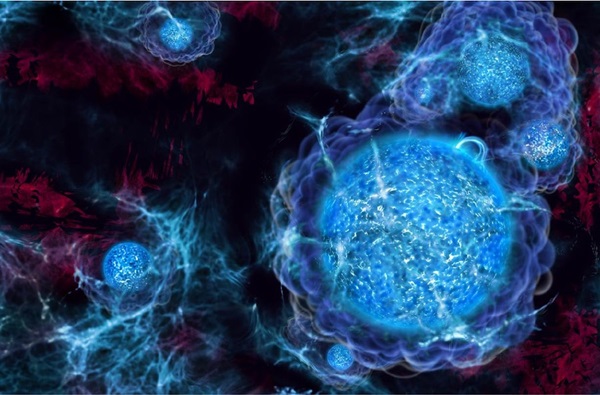

Powered by dark matter, dark stars are hypothetical objects that may have inhabited the early universe. If they existed, these mysterious beasts would not only have been the first stars to form in the cosmos, they also might explain how supermassive black holes got their start.

Fueled by dark matter

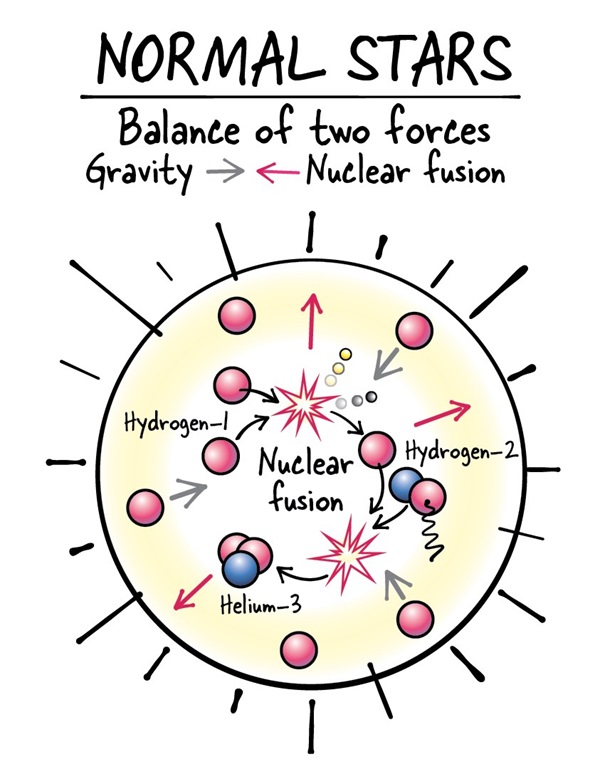

But for dark stars, the story’s a little different.

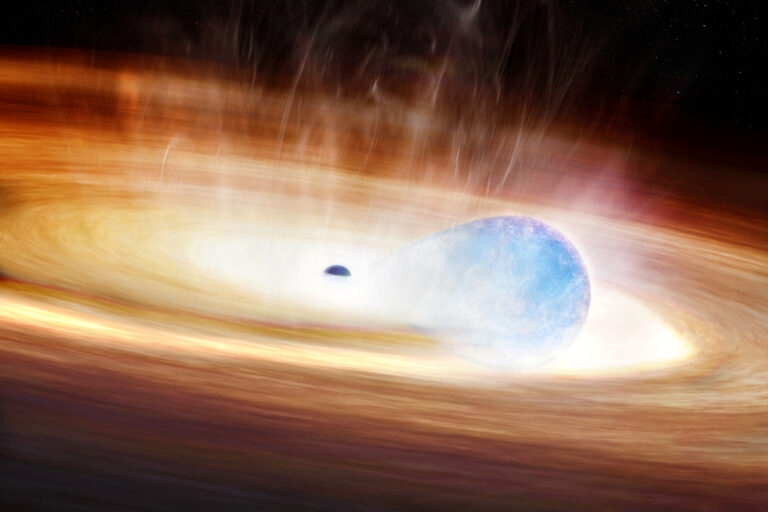

Theories suggest that dark stars would be mostly made from the same material as normal stars — namely, hydrogen and helium. But because these hypothetical dark stars would have formed in the early universe, when the cosmos was a lot denser, they also likely contain a small but significant amount of dark matter in the form of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) — a leading dark matter candidate.

These WIMPs are thought to serve as their own antimatter particles, they can annihilate with one another, producing pure energy. Within a dark star, these extremely powerful WIMP annihilations could offer enough outward pressure to prevent the star’s collapse without the need for core fusion.

According to dark star researcher Katherine Freese, the Kodosky Endowed Chair of Physics at UT-Austin, WIMPs only make up about 0.1 percent of a dark star’s total mass. But just this tiny bit of WIMP fuel could keep a dark star chugging along for millions or even billions of years.

What did dark stars look like?

Dark stars don’t just behave differently than normal stars. They also look different.

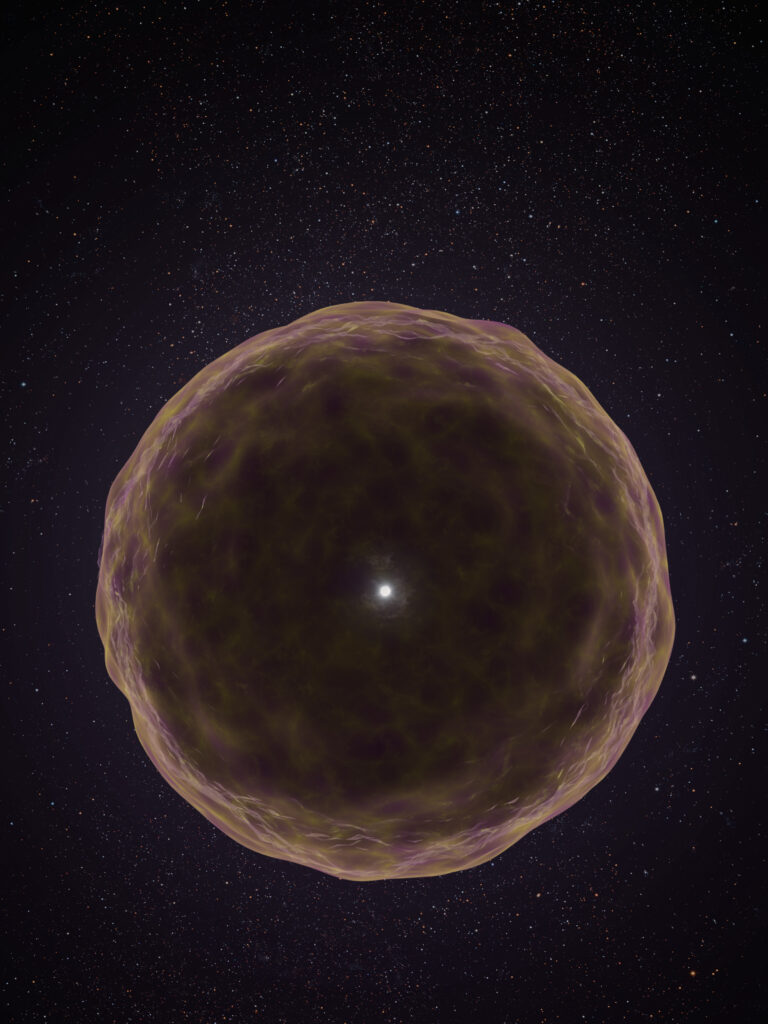

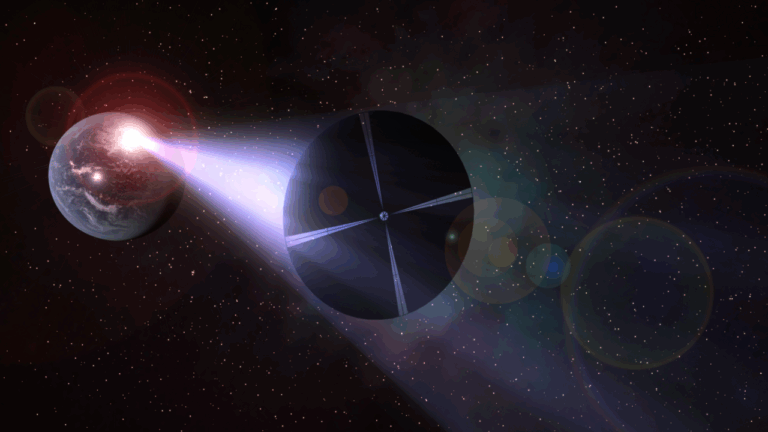

Because dark stars don’t rely on core fusion to stave off gravitational collapse, they’re not extremely compressed like normal stars. Instead, dark stars are likely giant, puffy clouds that shine extremely bright. Due to their bloated nature, Freese says, dark stars could even reach diameters of up to about 10 astronomical units (AU), where 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Searching for dark stars

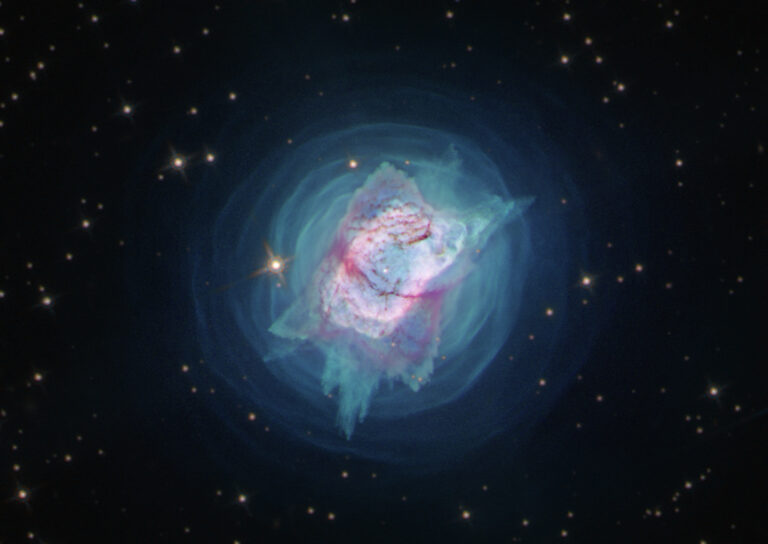

One of the hurdles to proving dark stars truly exist, though, is that these ironically bright objects depend on dark-matter annihilations to survive. However, such annihilations primarily occurred in the very early universe, when dark-matter particles were sharing close quarters. So, in order to spot ancient dark stars, we need telescopes capable of peering back to the extremely distant past.

Fortunately, according to Freese, the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope should be able to spot dark stars — as long as we know what to look for.

“They would look completely different from hot stars,” Freese told Astronomy. “Dark stars are cool [17,500 °F (9,700 °C)]. So, they would look more like the Sun in terms of frequency of light, even though they’re much brighter. That combination of cool and bright is hard to explain with other objects.”

“It is an exciting prospect that an entirely new type of star may be discovered in these upcoming data,” Freese and her colleagues wrote in a review paper.

Seeding supermassive black holes

If researchers are able to uncover evidence for the existence of dark stars, it would change how we think about the early stages of the universe. Darks stars would swiftly become the top candidates for the first generation of stars, which formed some 200 million years after the Big Bang.

But dark stars might also explain one of the most nagging questions in cosmology: How did supermassive black holes first form?

“If a dark star of a million solar masses were found [by James Webb] from very early on, it’s pretty clear that such an object would end up as a big black hole,” Freese says. “Then these could merge together to make supermassive black holes. A very reasonable scenario!”

To learn more about dark stars, check out Astronomy’s October 2018 feature: “Dark stars come into the light” or Freese’s 2016 paper published in the journal Reports on Progress in Physics entitled “Dark stars: a review.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to include Katherine Freese’s current academic affiliation. She is now at the University of Texas at Austin.