Key Takeaways:

Born in 1911, Brennecke earned her degree in chemistry from the Ohio State University in 1934 and continued on with graduate research in metallurgy at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the University of Pittsburgh; and the University of California in Los Angeles.

She went on to work as a metallurgist for the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) for 22 years, including during World War II. Her work included finding the best materials and welding techniques for aircraft, bridges, and even the landing craft made famous during the D-Day invasion at Normandy in 1944.

Building the mighty Saturn

Brennecke made the leap to NASA in 1961, at the beginning of the Apollo program. In a 2004 oral history interview conducted by NASA, she recalled her thoughts on the change in employment: “When NASA came into being, I was intrigued. I remember [President John Fitzgerald] Kennedy in May 1961 came up with a challenge to the Moon before the end of the decade. … I was thrilled with the prospect of being involved in this challenge, particularly with its ‘we will win’ leadership. I [had] been in Russia in 1958 and I wanted desperately for the U.S. to get ahead of the Russians in space. To me, here was our opportunity and I could be a part of it.”

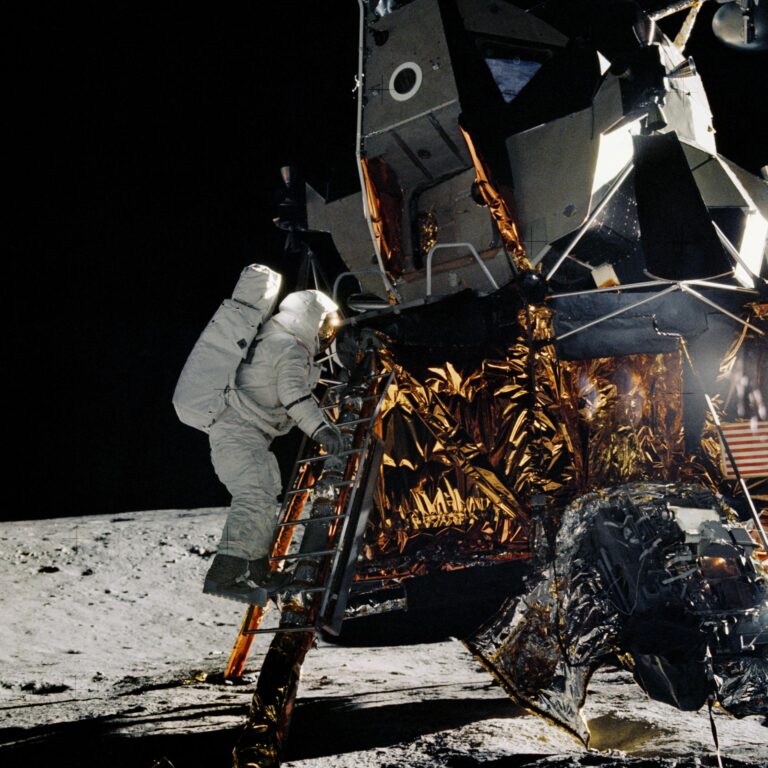

She joined NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center as a welding expert, working specifically on the mighty Saturn rockets that made up the backbone of the space age. The Saturn V rocket, used for the Apollo missions, is still the only vehicle to ever carry humans beyond low-Earth orbit.

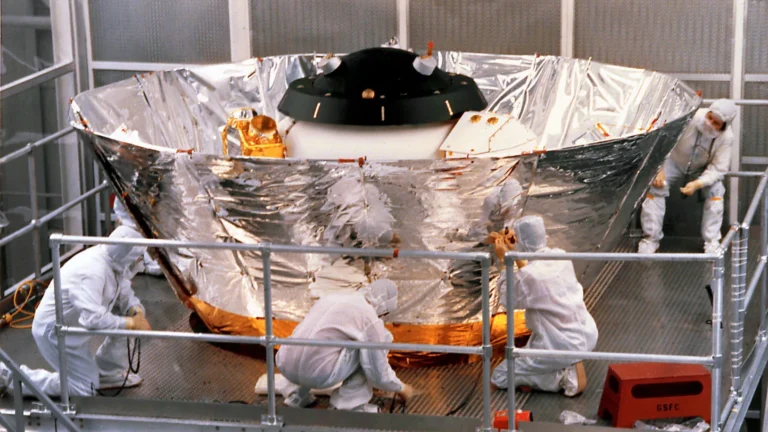

For the enormous Saturn stages, NASA needed materials that was both lightweight and strong. Thanks to her extensive experience, little of what Brennecke did was literal welding with a blowtorch in hand. Instead, she was responsible for deciding which materials and techniques should be used for the rockets. Brennecke’s major contribution was to craft the cryogenic fuel tanks. These tanks not only held supercooled fuel, they would also be subject to intense heat during launch. The weld points between different sections needed to be strong and immune to leaks. Brennecke helped to ensure the final results was what NASA needed to succeed.

Pushing boundaries

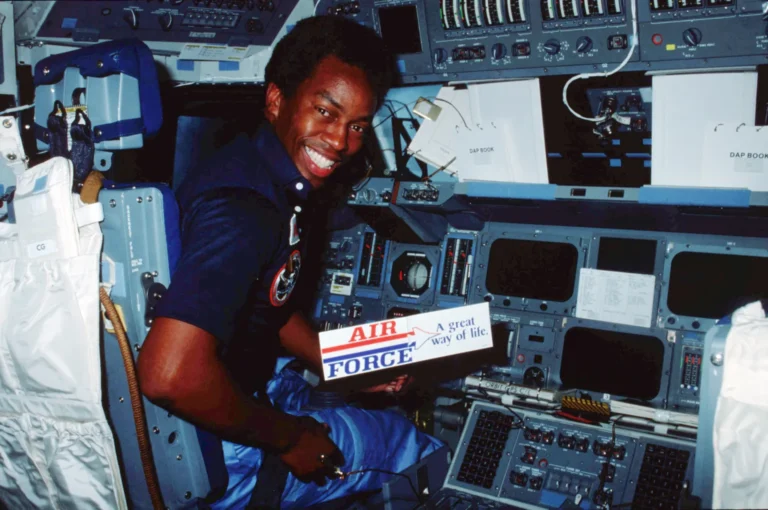

As the Apollo and Saturn programs wound down, Brennecke remained with NASA. She transferred to selecting materials and techniques for Spacelab and the Space Shuttle’s booster rockets, ushering in the next era of NASA’s human space exploration. Brennecke died in 2008.