Key Takeaways:

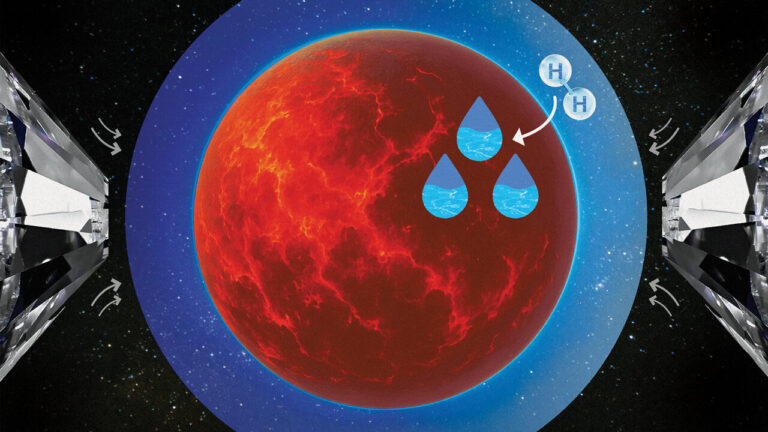

Saturn’s moon Titan is a distant and frigid world, but it also carries intriguing similarities to Earth’s own terrain. Liquid lakes and seas dot its landscape, though the methane and ethane that fill them are a far cry from terrestrial water. Now a new theory suggests that some of these bodies of liquid may have literally exploded into existence. If so, Titan may share another similarity with Earth: climate change.

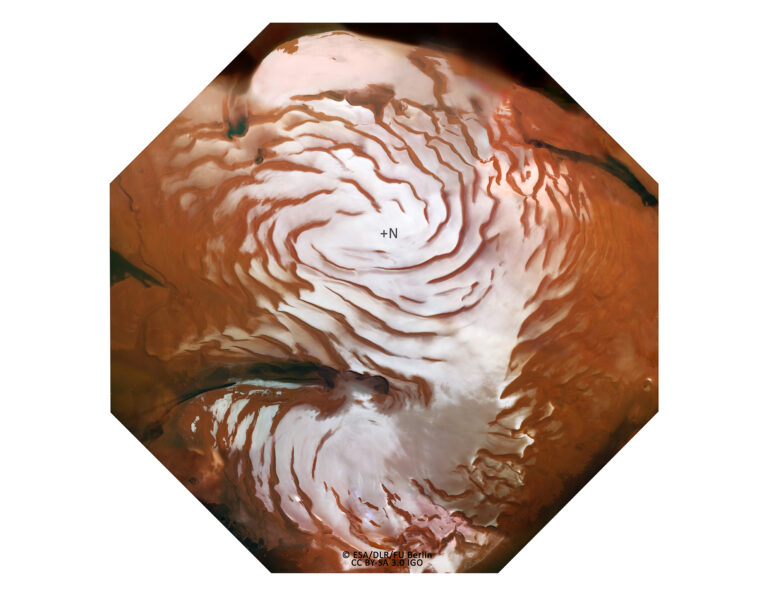

In a study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, researchers propose that pockets of liquid nitrogen may have exploded from the moon’s crust in response to warming atmospheric conditions. The resulting craters may then have filled with liquid methane.

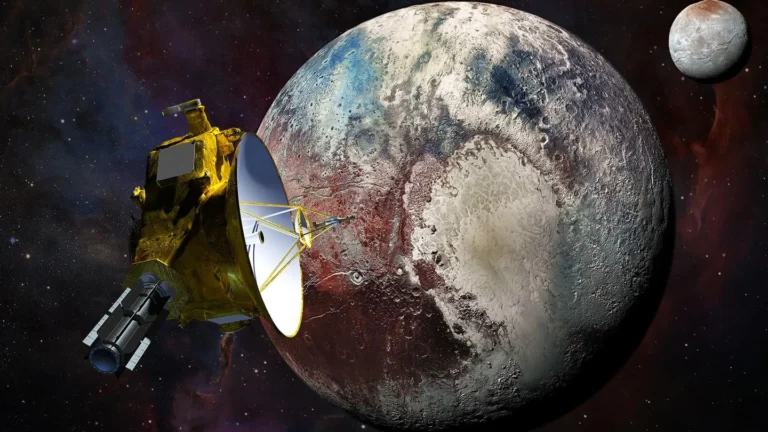

Study co-author Jonathan Lunine, an astronomer at Cornell University in New York, says that data from NASA’s Cassini mission inspired the new theory. The spacecraft spotted “odd, very striking features” around some of Titan’s lakes. The lakes were surrounded by sharp ridges and ramparts that couldn’t be explained by previous theories about how the lakes formed. But they could be explained as the results of explosions.

The researchers compared these lakes to terrestrial formations like the Hopi Buttes Volcanic Field in Arizona.

The study’s lead author, Giuseppe Mitri of G. D’Annunzio University in Italy, says that these exploding crater lakes are evidence of climate change on Saturn’s largest moon – the only satellite in our solar system with a significant atmosphere.

“[It] is evidence that Titan has experienced at least one episode of climate change from a colder period in the past,” he says. That’s likely due to changing levels of methane, a warming greenhouse gas, Mitri says, adding that the exact cause of cooling and warming on Titan is open to debate.

“The idea that the pits within which Titan’s lakes reside are explosive in origin is new and intriguing,” says Oded Aharonson, a planetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel who was not involved in the study.

And the raised rims on these lakes have long been a puzzle, according to Ralph Lorenz, a veteran planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory. He says that, while some sort of spraying or frothing seems like a reasonable explanation for how they formed, there may be ways they could have built up progressively “without invoking quite so catastrophic a scenario.” He adds that Titan’s chemistry and physical process offer much more to explore.

And while the Cassini spacecraft was intentionally plunged into Saturn in 2017, Lunine expects many more intriguing discoveries about Titan to come from from the mission’s data over the next decade. Scientists are still studying the datasets collected during the mission. Other opportunities could come from Dragonfly, a robotic lander that NASA plans to launch to Titan in 2026 which may also provide clarity about changes in the moon’s climate.

Though it’s unlikely humans will visit Titan in the near future, Lunine jokes that visiting one of Earth’s explosion crater lakes, such as Italy’s Lago di Nemi, might be the next best thing. “Someday, I could sit at the top of one of those overlooks and sip a nice glass of Italian wine and look down at the lake and imagine that I’m not in Rome but I’m on Titan,” he says. “It’s not water down there, it’s liquid methane.”