Key Takeaways:

- Three cosmonauts died in space due to a depressurized spacecraft.

- The Soyuz 11 accident was caused by a faulty valve.

- The accident resulted in immediate changes to cosmonaut safety protocols.

- All cosmonauts now wear pressurized suits during re-entry.

For many wannabe astronauts, the idea of venturing into the great unknown would be a dream come true. But over the past 50 years, there’s been a slew of spaceflight-related tragedies that are more akin to an astronaut’s worst nightmare.

In the last half-century, about 30 astronauts and cosmonauts have died while training for or attempting dangerous space missions. But the vast majority of these deaths occurred either on the ground or in Earth’s atmosphere — below the accepted boundary of space called the Kármán line, which begins at an altitude of about 62 miles (100 kilometers).

However, of the roughly 550 people who have so far ventured into space, only three have actually died there.

The fatal frontier

Early in the space race, both NASA and the USSR experienced a surge in deadly jet crashes that killed a number of pilots testing advanced rocket-propelled planes. Then, of course, there was the Apollo 1 fire in January 1967, which killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee in a horrific manner. During a launch simulation, a stray spark within the cabin of the grounded spacecraft, which was filled with pure oxygen, ignited. This led to an uncontrollable fire that quickly overwhelmed the doomed crew, leading to their tragic deaths as they struggled in vain to open the pressurized hatch door.

“We had done exactly the same test the night before but without the hatch closed, so we weren’t on 100 percent oxygen,” Walter Cunningham, Lunar Module Pilot of Apollo 7, told Astronomy. “So, when the [Apollo 1] crew died, it was a couple of weeks later before they started picking up the pieces, and at which point we were assigned the prime crew of the first manned Apollo mission.” A little less than two years later, in October 1968, Cunningham, Wally Schirra, and Donn Eisele became the first Apollo crew to successfully venture into space.

Over the next three years, Apollo astronauts completed seven more missions — including the first Moon landing during Apollo 11 and the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission. Then, on June 30, 1971, humankind witnessed the first (and, so far, only) deaths to occur in space.

The Soyuz 11 disaster

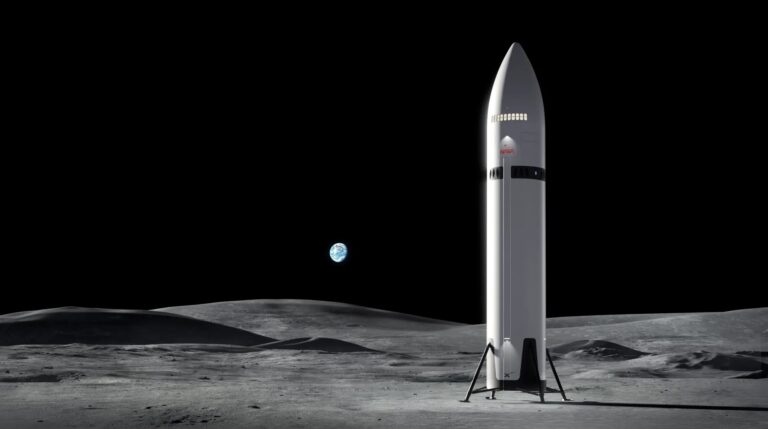

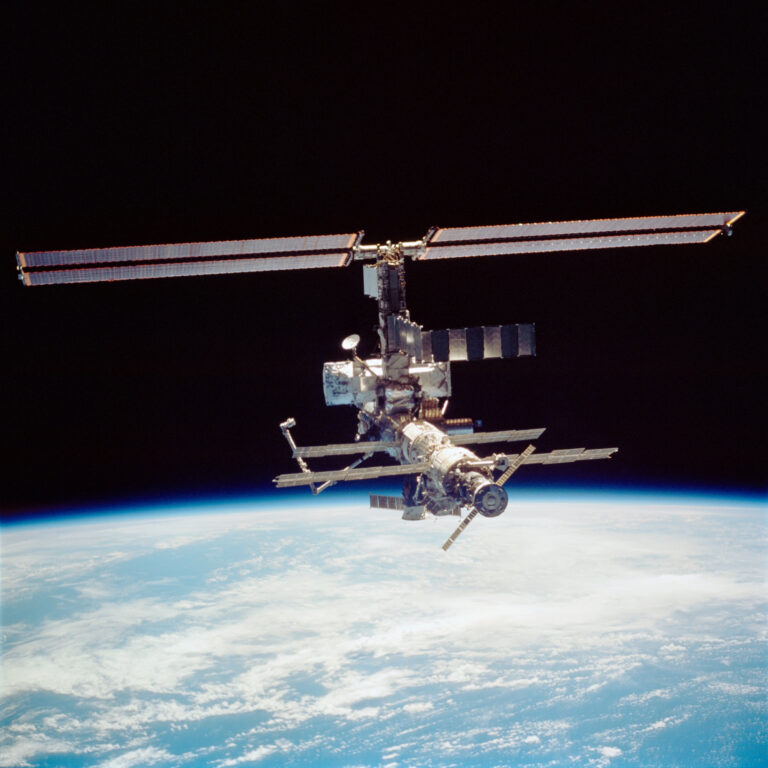

The first space station to park itself above Earth’s atmosphere was the USSR’s Salyut 1, which launched (unmanned) on April 19, 1971. Just a few days later, a crew of three Soviets blasted off aboard Soyuz 10 with the goal of entering the space station and staying in orbit for a full month. Though the Soyuz 10 crew docked safely with the Salyut 1, issues with the entry hatch prevented them from entering the space station. During their premature return trip back to Earth, toxic chemicals leaked into the air supply of Soyuz 10, causing one cosmonaut to pass out. However, all three members of the crew ultimately made it home safe with no long-lasting effects.

Just a few months later, on June 6, the Soyuz 11 mission took another crack at accessing the space station. Unlike the previous crew, the three Soyuz 11 cosmonauts — Georgi Dobrovolski, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev — successfully entered Salyut 1. Once aboard, they spent the next three weeks not only setting a new record for the longest time spent in space, but also carrying out loads of experiments focused on how the human body deals with extended periods of weightlessness.

On June 29, the cosmonauts loaded back into the Soyuz 11 spacecraft and began their descent to Earth. And that’s when tragedy struck.

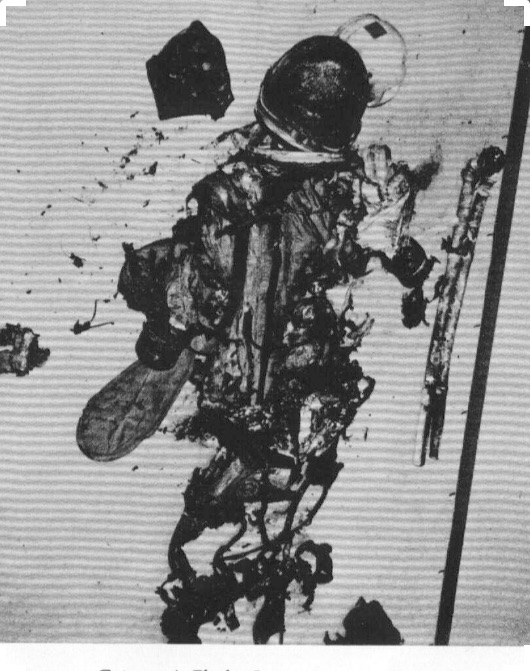

To those on the ground, everything about Soyuz 11’s reentry seemed to go off without a hitch. The spacecraft appeared to make it through the atmosphere just fine, ultimately landing in Kazakhstan as planned. It wasn’t until recovery crews opened the hatch that they discovered all three crew members inside were dead.

“Outwardly, there was no damage whatsoever,” recalled Kerim Kerimov, chair of the State Commission, in Ben Evans’ book Foothold in the Heavens. “[The recovery crew] knocked on the side, but there was no response from within. On opening the hatch, they found all three men in their couches, motionless, with dark-blue patches on their faces and trails of blood from their noses and ears. They removed them from the descent module. Dobrovolski was still warm. The doctors gave artificial respiration. Based on their reports, the cause of death was suffocation.”

The fatal accident was determined to be the result of a faulty valve seal on the spacecraft’s descent vehicle that burst open during its separation from the service module. At an altitude of 104 miles (168 km), the deadly combination of a leaking valve and the vacuum of space rapidly sucked all the air out of the crew cabin, depressurizing it. And because the valve was hidden below the cosmonauts’ seats, it would have been nearly impossible for them to fix the problem in time.

During an early NASA vacuum test, Jim Leblanc’s pressurized suit began to lose air, leading to decompression. Within about 30 seconds, he passed out, but his coworkers fortunately were able to get to him in time to save his life.

As a direct result of the decompression deaths of the Soyuz 11 crew, the USSR quickly made the shift to requiring all cosmonauts to wear pressurized space suits during reentry — a practice that’s still in place today.