A powerful new astronomical instrument got its first view of the sky from an Arizona mountaintop two weeks ago. Once the device officially gets to work in early 2020, it will capture the light from thousands of galaxies each night — up to 5,000 galaxies every 20 minutes, in ideal conditions. With this instrument, researchers will make a deep-space map of where galaxies lie to study dark energy throughout the history of the universe.

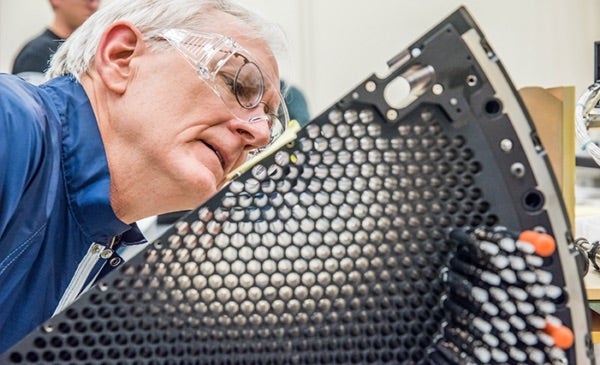

Scientists installed the device, called the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), on a telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory over a period of 18 months. And on October 22, DESI turned its gaze to the night sky to make its first test observations. Over the next few months, the DESI team will finish testing and begin its survey in earnest.

How to map the universe

In just five years, the instrument is expected to gather light from 35 million galaxies and 2.4 million quasars, or galaxies with huge jets beaming from the supermassive black holes in their centers.

DESI will observe so many galaxies thanks to a complicated dance of machinery. Robotic “positioners” can arrange 5,000 fiber-optic cables into pre-set locations in the instrument in just a couple of minutes. Each of the 5,000 fibers, which are about as wide as human hair, will collect light from one galaxy in the telescope’s view of the sky.

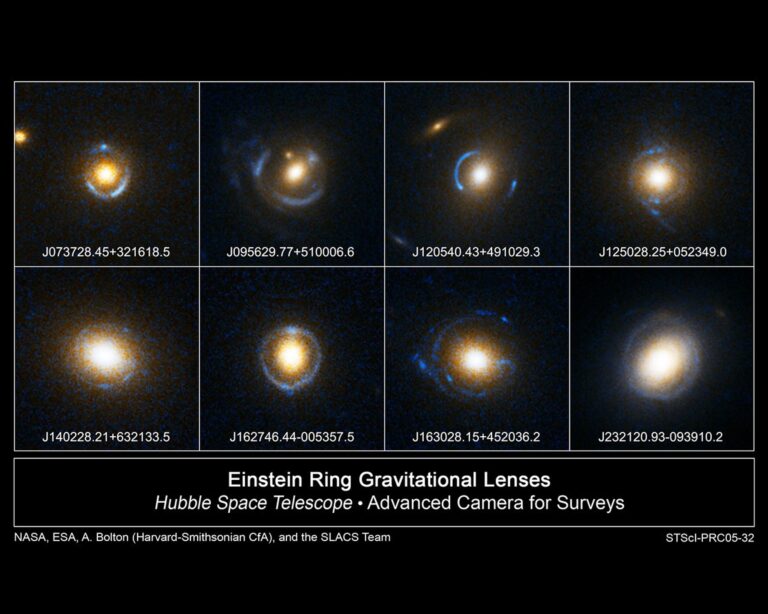

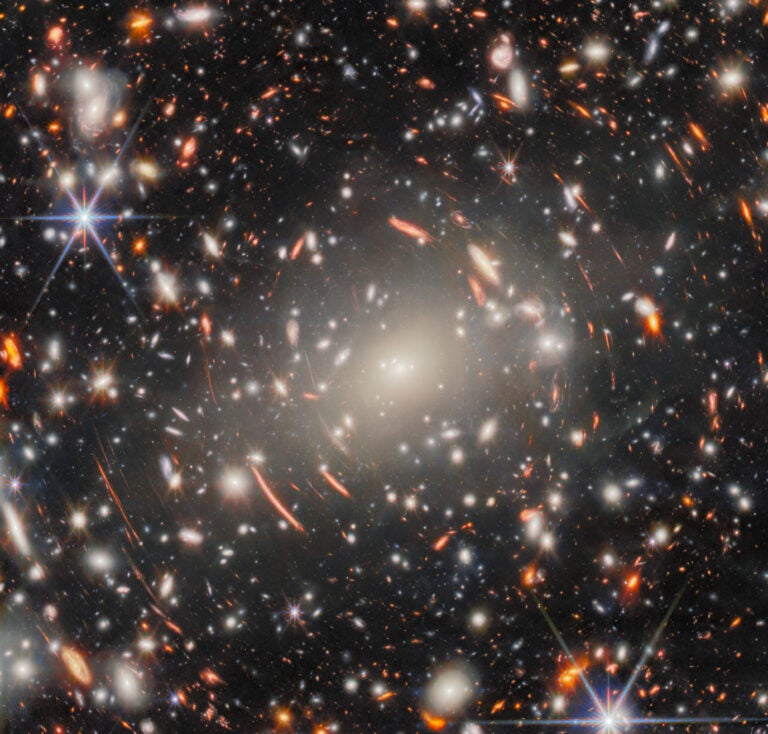

By collecting specific wavelengths of light from these galaxies, DESI will let astronomers measure how quickly these objects are moving away from us because of the universe’s expansion. They’ll also be able to measure how far the galaxies are from us, relative to each other. From the galaxies’ locations in the sky and their relative distances, astronomers will make a 3-D map of where the galaxies lie in space up to 11 billion light-years away.

Is dark energy constant?

What does this map of galaxies have to do with dark energy? Dark energy is the mysterious force that makes the universe’s expansion accelerate.

So by measuring how fast galaxies are moving thanks to the universe’s expansion, astronomers can estimate how much dark energy there is. And thanks to DESI ability to measure millions of distant galaxies, astronomers can measure how much dark energy there was at a given point of time in the universe’s history, up to 11 billion years ago.

That’s the main goal behind making such an expansive map of galaxies deep into space. DESI should be able to help determine whether the amount of dark energy in the universe stayed the same over time, as today’s standard ideas of cosmology predict. Or, alternatively, if the amount of dark energy somehow changed over the universe’s history.

“I’m very excited to see the maps that this facility will be able to make, and to see how our theories of cosmological structure information can get challenged and extended by this enormously large dataset,” said Daniel Eisenstein, a Harvard University astronomer and a member of the DESI team.