Do supermassive black holes have friends? The nature of galaxy formation suggests that the answer is yes, and in fact, pairs of supermassive black holes should be common in the universe.

I am an astrophysicist and am interested in a wide range of theoretical problems in astrophysics, from the formation of the very first galaxies to the gravitational interactions of black holes, stars and even planets. Black holes are intriguing systems, and supermassive black holes and the dense stellar environments that surround them represent one of the most extreme places in our universe.

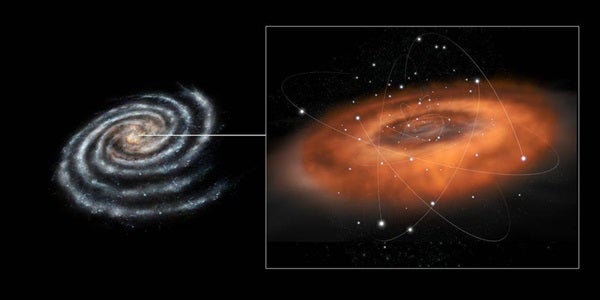

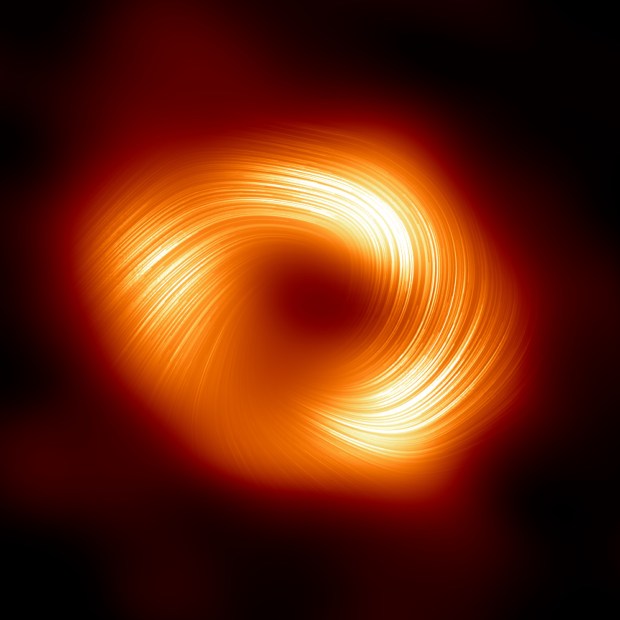

The supermassive black hole that lurks at the center of our galaxy, called Sgr A*, has a mass of about 4 million times that of our Sun. A black hole is a place in space where gravity is so strong that neither particles or light can escape from it. Surrounding Sgr A* is a dense cluster of stars. Precise measurements of the orbits of these stars allowed astronomers to confirm the existence of this supermassive black hole and to measure its mass. For more than 20 years, scientists have been monitoring the orbits of these stars around the supermassive black hole. Based on what we’ve seen, my colleagues and I show that if there is a friend there, it might be a second black hole nearby that is at least 100,000 times the mass of the Sun.

Supermassive black holes and their friends

Almost every galaxy, including our Milky Way, has a supermassive black hole at its heart, with masses of millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. Astronomers are still studying why the heart of galaxies often hosts a supermassive black hole. One popular idea connects to the possibility that supermassive holes have friends.

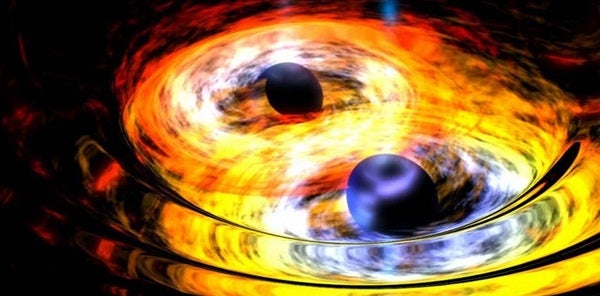

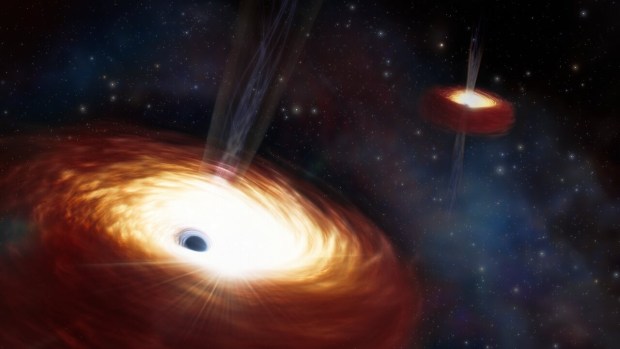

To understand this idea, we need to go back to when the universe was about 100 million years old, to the era of the very first galaxies. They were much smaller than today’s galaxies, about 10,000 or more times less massive than the Milky Way. Within these early galaxies the very first stars that died created black holes, of about tens to thousand the mass of the Sun. These black holes sank to the center of gravity, the heart of their host galaxy. Since galaxies evolve by merging and colliding with one another, collisions between galaxies will result in supermassive black hole pairs – the key part of this story. The black holes then collide and grow in size as well. A black hole that is more than a million times the mass of our son is considered supermassive.

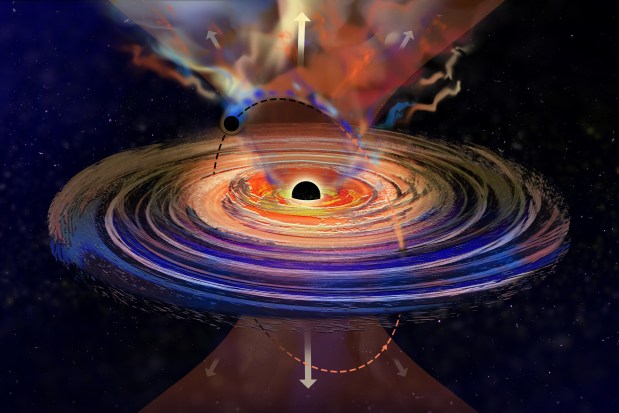

If indeed the supermassive black hole has a friend revolving around it in close orbit, the center of the galaxy is locked in a complex dance. The partners’ gravitational tugs will also exert its own pull on the nearby stars disturbing their orbits. The two supermassive black holes are orbiting each other, and at the same time, each is exerting its own pull on the stars around it.

The gravitational forces from the black holes pull on these stars and make them change their orbit; in other words, after one revolution around the supermassive black hole pair, a star will not go exactly back to the point at which it began.

Using our understanding of the gravitational interaction between the possible supermassive black hole pair and the surrounding stars, astronomers can predict what will happen to stars. Astrophysicists like my colleagues and me can compare our predictions to observations, and then can determine the possible orbits of stars and figure out whether the supermassive black hole has a companion that is exerting gravitational influence.

Using a well-studied star, called S0-2, which orbits the supermassive black hole that lies at the center of the galaxy every 16 years, we can already rule out the idea that there is a second supermassive black hole with mass above 100,000 times the mass of the Sun and farther than about 200 times the distance between the Sun and the Earth. If there was such a companion, then I and my colleagues would have detected its effects on the orbit of SO-2.

But that doesn’t mean that a smaller companion black hole cannot still hide there. Such an object may not alter the orbit of SO-2 in a way we can easily measure.

The physics of supermassive black holes

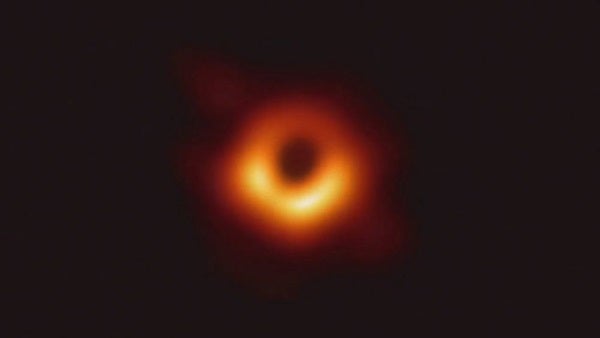

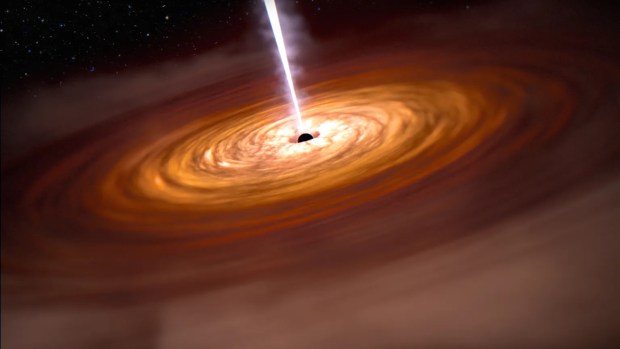

Supermassive black holes have gotten a lot of attention lately. In particular, the recent image of such a giant at the center of the galaxy M87 opened a new window to understanding the physics behind black holes.

The proximity of the Milky Way’s galactic center – a mere 24,000 light-years away – provides a unique laboratory for addressing issues in the fundamental physics of supermassive black holes. For example, astrophysicists like myself would like to understand their impact on the central regions of galaxies and their role in galaxy formation and evolution. The detection of a pair of supermassive black holes in the galactic center would indicate that the Milky Way merged with another, possibly small, galaxy at some time in the past.

That’s not all that monitoring the surrounding stars can tell us. Measurements of the star S0-2 allowed scientists to carry out a unique test of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. In May 2018, S0-2 zoomed past the supermassive black hole at a distance of only about 130 times the Earth’s distance from the Sun. According to Einstein’s theory, the wavelength of light emitted by the star should stretch as it climbs from the deep gravitational well of the supermassive black hole.

The stretching wavelength that Einstein predicted – which makes the star appear redder – was detected and proves that the theory of general relativity accurately describes the physics in this extreme gravitational zone. I am eagerly awaiting the second closest approach of S0-2, which will occur in about 16 years, because astrophysicists like myself will be able to test more of Einstein’s predictions about general relativity, including the change of the orientation of the stars’ elongated orbit. But if the supermassive black hole has a partner, this could alter the expected result.

Finally, if there are two massive black holes orbiting each other at the galactic center, as my team suggests is possible, they will emit gravitational waves. Since 2015, the LIGO-Virgo observatories have been detecting gravitational wave radiation from merging stellar-mass black holes and neutron stars. These groundbreaking detections have opened a new way for scientists to sense the universe.

Any waves emitted by our hypothetical black hole pair will be at low frequencies, too low for the LIGO-Virgo detectors to sense. But a planned space-based detector known as LISA may be able to detect these waves which will help astrophysicists figure out whether our galactic center black hole is alone or has a partner.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.