Key Takeaways:

Based on the chemical properties of tiny micrometeorites that fell to Earth 2.7 billion years ago, a team of researchers says that the planet’s atmosphere was likely chock-full of carbon dioxide back then. From their models, the researchers estimate that carbon dioxide made up anywhere from 6 percent to more than 70 percent of our ancient atmosphere. By comparison, our atmosphere today is 0.04 percent carbon dioxide.

The researchers reported their findings in a paper published Jan. 22 in Science Advances.

Ancient atmospheric records

From rock records, scientists know that there wasn’t much oxygen at Earth’s surface during the Archean eon, a period of time stretching from 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago. Researchers think there were probably a lot of greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide or methane, on Earth around this time. But they don’t know which ones or how much.

“It’s really hard,” said Owen Lehmer, a University of Washington researcher and an author of the new paper. “There’s very few things that record atmospheric composition that we can find today.”

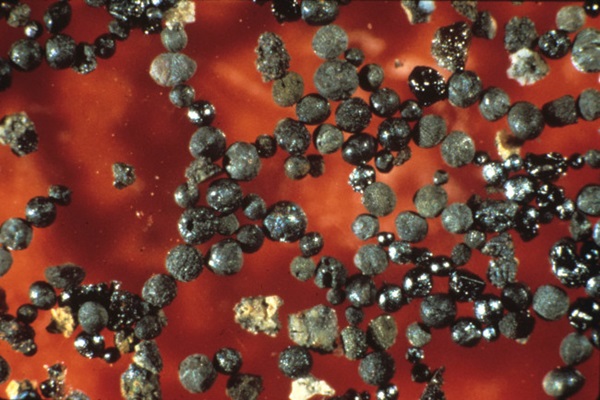

But a few years ago, scientists found micrometeorites — rocky or metallic particles the size of sand grains — that had fallen to Earth some 2.7 billion years back, making them the oldest micrometeorites yet found. As the micrometeorites hurtled through the atmosphere toward Earth, they would have heated up, melted and interacted with gases in the atmosphere, potentially preserving a record of what was there at the time.

A carbon dioxide world

The micrometeorites contained a lot of iron, some of which had turned into a compound called wüstite that can form when iron interacts with oxygen. Wüstite can’t form on Earth’s surface, so the micrometeorites must have encountered oxygen while they fell through the atmosphere — if not as oxygen gas, then maybe as carbon dioxide.

To see what levels of carbon dioxide and other gases would create the minerals they saw, Lehmer and others ran computer models of iron-rich micrometeorites falling through Earth’s atmosphere with various concentrations of carbon dioxide. They then compared their simulated micrometeorites to the real ones. The team found that an atmosphere with lots of carbon dioxide — tens of percent by volume, and possibly 70 percent or more — would make micrometeorites with the right amounts of wüstite.

Having such high levels of carbon dioxide would have been fortuitous for early organisms, given that the sun was dimmer in the past and Earth would have been receiving less light. The high concentrations of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would have kept the planet warm enough for liquid water and life.

To pin down a more precise number for just how much carbon dioxide was in Earth’s atmosphere around this time, Lehmer said, they’d need more micrometeorites to compare their models to.

But he’s excited that they were able to estimate the carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere this way. If they can find even older examples of micrometeorites with wüstite, they could potentially figure out how much carbon dioxide was in Earth’s atmosphere over time and paint a clearer picture of the early Earth’s history.