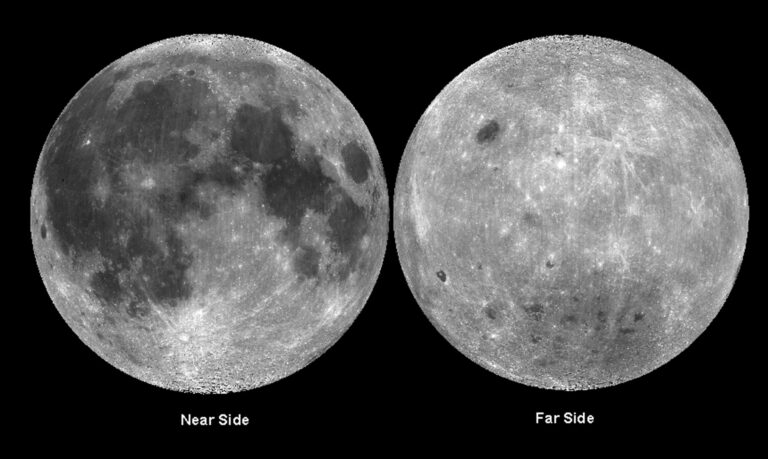

It’s further evidence that the Moon’s entire surface — not just the limited parts that astronauts explored — is deeply covered in the fluffy Moon dirt that astronomers call regolith.

In January 2019, China’s Chang’e-4 lander, along with a rover named Yutu-2 (Chinese for Jade Rabbit), touched down on the Moon’s farside. It landed inside Von Kármán crater, a large impact site nestled inside the even more enormous South Pole-Aitken Basin crater. Aitken is the widest, deepest and oldest crater on the Moon. That status has made it a prime target for scientists who want to study how the 1,600-mile-wide (2,575 kilometers) basin formed and evolved over billions of years.

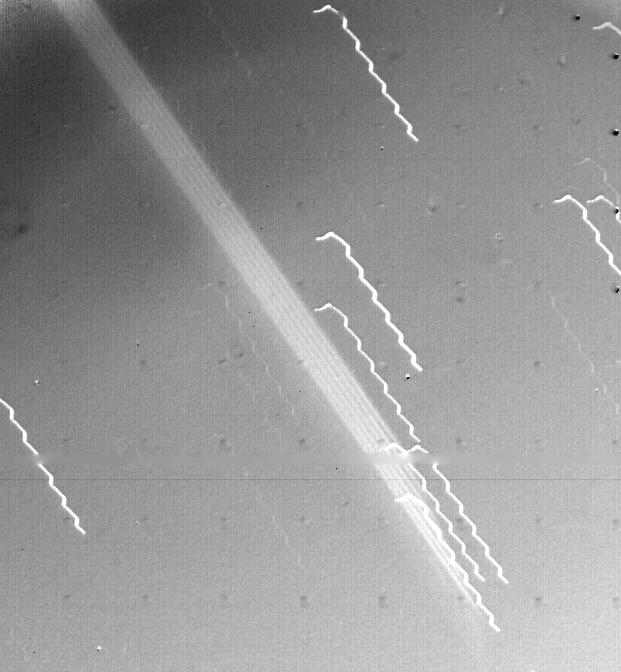

Yutu-2 was well equipped to probe below the surface thanks to ground-penetrating radar, which sends pulses through the world’s subsurface and measures the signals that reflect back. It found that the landing site is carpeted with loose dirt that extends up to 40 feet (12 meters) deep, according to a paper published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Are you ready to take a closer look at the Moon? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Your guide to the Moon.

Delving into Moon dust

NASA astronauts and experiments, as well as the Soviet Luna missions, showed that this pulverized dust and rock is prevalent across the near side of the Moon. And while scientists have spent decades studying regolith, they weren’t sure if it would also be prevalent across the vast unexplored lunar reaches.

Regolith was a major challenge during the Apollo missions. It soiled both scientific equipment and space suits. Some scientists initially thought the dust might be so thick that spacecraft would simply sink down into it. And NASA is still concerned about the health hazards regolith could pose to future astronauts.

Yutu-2’s ground-penetrating radar also got a good look at the layers beneath the surface regolith. The Chinese-led team of scientists say they found alternating layers of boulders and large rocks interspersed with finer soil down to roughly 130 feet (40 m). Each of those layers of large rocks was probably deposited as space rocks hit the surface and filled the air with ejecta. Below that, their radar instruments couldn’t get a good signal. However, the scientists suspect this pattern extends even deeper.

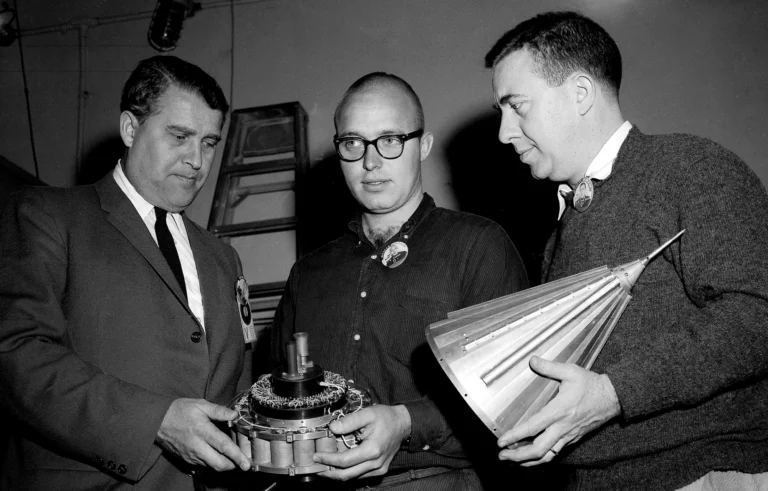

This isn’t the first time scientists have used radar to study the Moon’s subsurface. NASA’s Apollo 17 mission in 1972 carried the Lunar Sounder Experiment, which was used to study the ground beneath craters across the Moon’s surface. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency has also flown an orbiting radar experiment.

Ongoing mission

The Chang’e-4 mission was initially designed to last through at least three lunar days, which is roughly three months back on Earth; on February 18, China’s state-run news agency reported the pair had begun their 15th lunar day. Both the rover and lander are still fully functional, according to a government release. Yutu-2 has traveled roughly 1,150 feet (350 m) since the mission began.

The spacecraft have endured more than a dozen cycles of hibernation during the long lunar nights, followed by powering back up once daylight returns. The rover also doesn’t operate at high noon, when the Sun is brightest and temperatures soar.

The mission’s results should ultimately help scientists better understand the Moon’s formation and evolution. And astronomers say that studying craters on the Moon can provide a proxy for researching what happens when large objects hit Earth.

“Chang’e-4 lived up to expectations, realizing the feat of the first soft landing of the human probe on the back of the Moon, with abundant scientific data and great scientific contributions,” reads a translation of a Chinese government press release posted in January. “Looking around the world, the hearts of countless Chinese children care about Chang’e-4.”