Key Takeaways:

Did life on Earth come from Mars, or perhaps even another star system?

For generations, some astronomers have speculated about whether our planet was pollinated with an alien seed. This theory, called panspermia, suggests that primitive life can travel from world to world on space rocks, kick-starting evolution in each new environment.

This all sounds more like science fiction than science, but there are also good reasons to think panspermia is possible.

With the recent discovery of the alien space rock ‘Oumuamua and the interstellar comet Borisov, some astronomers are rethinking how far life could travel to trigger a “Second Genesis.” Could life spread across the galaxy? If alien asteroids and comets commonly travel between stars, then the interstellar version of panspermia may be more possible than astronomers imagined.

“The statistics of interstellar objects was recalculated as a result of ‘Oumuamua and Borisov,” says Harvard University astronomer Avi Loeb. He’s been researching interstellar objects for more than a decade and is also known for some of the most controversial ideas about them. “It turns out that there is much more stuff in interstellar space (than expected).”

Did Earth life come from Mars?

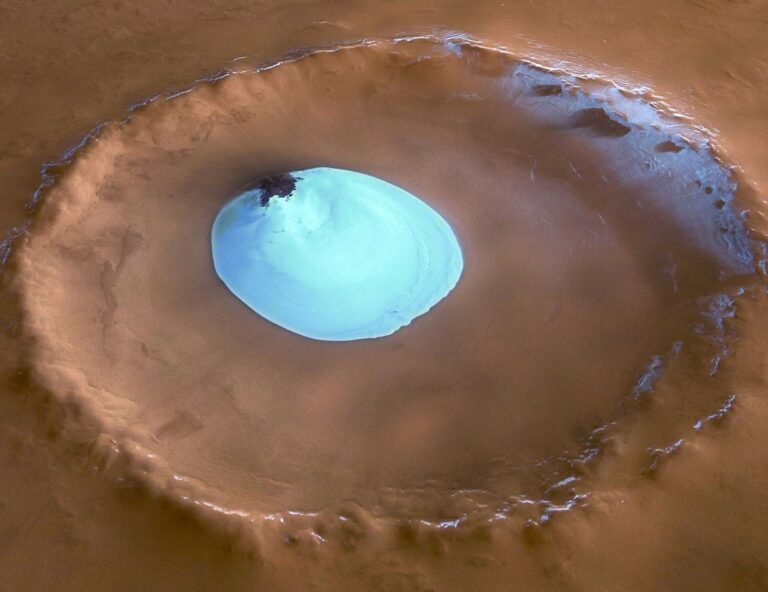

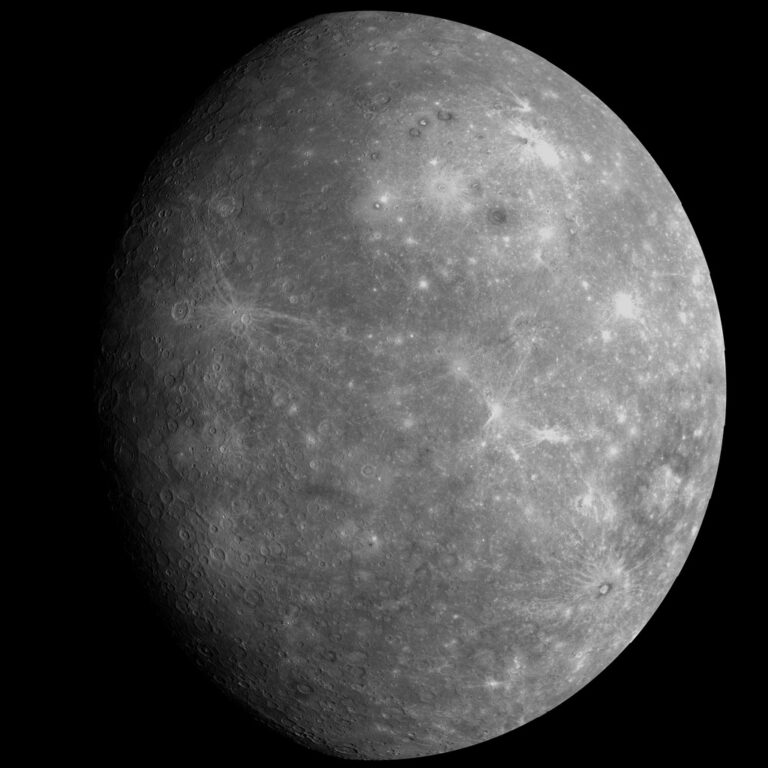

Some of the best evidence for panspermia comes from hints that Mars may have been habitable even before our own planet.

All life on Earth depends on DNA, the cellular code that lets species reproduce. DNA also has a biological precursor called RNA that’s capable of many of the same tricks. In lab settings, scientists have shown that RNA has an easier time than DNA does when emerging from organic materials like those found on young planets. And while early Earth was still swimming in water — enough to stop RNA from forming — Mars was much drier and probably had all the ingredients to create RNA.

As asteroids hit Mars, they would have launched its surface debris into space, where it would have traveled the solar system before some of it possibly landed on Earth. Some estimates suggests Mars material still lands on our home planet every day. So, if life evolved on Mars’ surface billions of years ago, and if life can survive being catapulted from one world to another, then theoretically, it would be possible that humanity descended from ancient Martians.

To prove this theory, future Mars explorers would have to first find life on Mars. All of this leads some experts in the field to think that if life exists on the Red Planet, we shouldn’t be surprised if it looks very similar to life at home.

Are you ready to take a closer look at Mars? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Mars: Exploring the Red Planet.

Life from other star systems

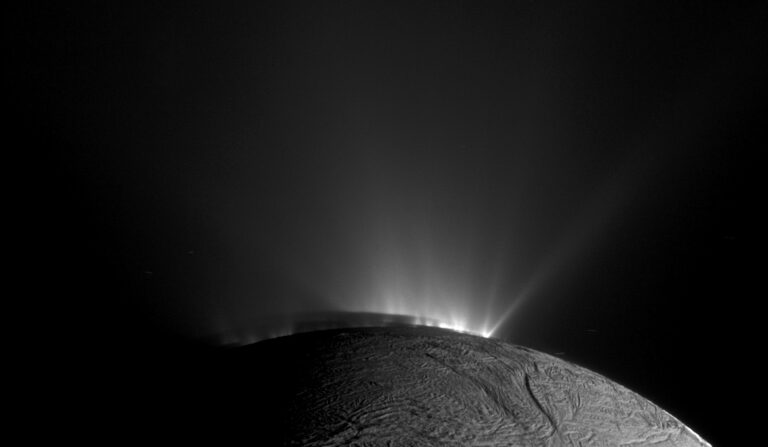

But it’s one thing for worlds within a solar system to cross-pollinate. It’s quite another for alien life to survive the light-years-long journey from one star to another. These extreme distances have pushed many astronomers to reject the idea of panspermia between star systems. The trip would require life to sit on an asteroid for perhaps hundreds of millions or even billions of years while it’s bombarded with cosmic radiation. Survival would depend on whether these microorganisms could get below the surface before they’re destroyed.

However, the recent discoveries of two interstellar visitors have brought new life to the idea.

In 2017, astronomers in Hawaii using the world’s top asteroid-hunting telescope discovered something totally new: a fast-moving object on an orbit that approached our Sun just once. It was the first known interstellar object to visit our solar system. And this space rock, named ‘Oumuamua, has some truly alien properties.

Astronomers had always expected to find interstellar comets. Their orbits at the outer edges of star systems should make it easy for a passing star to give them a gravitational bump that knocks them loose. However, the best estimates suggested astronomers wouldn’t start finding interstellar comets until bigger and better telescopes were built. Even more confusing, ‘Oumuamua looked like an asteroid. For starters, it lacked a distinct coma — the fuzzy envelope of sublimated ices created when comets get close to the Sun. The cigar-shaped object is also 10 times longer than it is wide. That’s far more elongated than anything seen in our own solar system.

“In my book, it’s still very peculiar,” Loeb says. “It’s a very weird object.”

And while astronomers are still debating if ‘Oumuamua was a comet or an asteroid, the space rock did leave a few clues about its composition. For one, it’s dense and rocky, perhaps even metallic. But there’s also evidence that it’s icy — a significant find because it implies those ices weren’t baked off over the eons.

Astronomers can’t say what star ‘Oumuamua came from, let alone if that system had Earth-like exoplanets. But based on its trajectory, the space rock must have been flung from its home star system at least several hundred thousand years ago, but it also could have circled the Milky Way several times on a course that’s lasted billions of years.

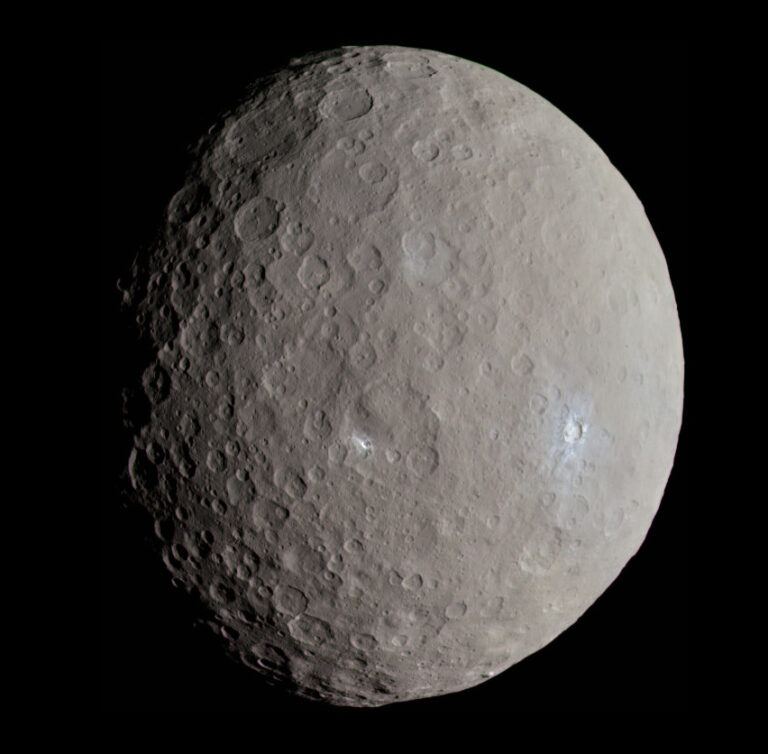

Alien space rocks everywhere

Astronomers named this strange object ‘Oumuamua because it roughly translates as “first distant messenger” in Hawaiian. And that status as a harbinger of things to come will likely be it’s most lasting impact. In the wake of the discovery, one study suggested that a couple interstellar space rocks may pass within the orbit of Mercury every year.

Scientists didn’t have to wait long to discover another alien space rock, either. In 2019, astronomers found C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), a much clearer case of an interstellar comet.

These new finds led astronomers to increase estimates of how many interstellar objects are out there. And they’re also pushing some researchers to take a second look at the idea that life could star hop from system to system, pollinating the Milky Way with life.

One estimate, published in The Astronomical Journal in 2018, calculated that a large interstellar object like ‘Oumuamua could hit Earth once every 10 million to 100 million years. The study authors, Loeb and fellow Harvard astronomer Manasvi Lingam, also took that idea a step further by invoking a long-standing theory in paleontology that suggests large asteroids hit Earth roughly every 26 million years. Some have suggested this periodicity comes from close encounters with neighboring stars that fling comets our way. Loeb and Lingam asked: What if, instead of comets from our own solar system, these extinction-inducing space rocks were actually interstellar objects from a passing star?

Life on comets

But how could life find its way onto a comet? According to Loeb, Earth and other worlds may not even need to be hit by space rocks to send microbes out into the cosmos.

In a January 2019 study published in the International Journal of Astrobiology, Loeb and a Harvard undergraduate student, Amir Siraj, suggest that Earth-grazing comets and interstellar objects could have snagged microbes from high in our atmosphere and then carried them out into the Milky Way. Their estimates predict this could have already happened many times, depending on how high up life exists on our planet.

“We found that there could be thousands, if not tens of thousands, that could pass through the Earth’s atmosphere, collect microbes, and then get kicked to another solar system,” Loeb says.

Loeb and Siraj even think they may have identified the first known interstellar meteor by mining existing databases and studying known object’s trajectories. However, they won’t be sure until they can get someone with a U.S. government security clearance to provide them with the classified raw data. The object was likely picked up by a missile alert system, but Loeb says he’s struggled to get the information they need to finish their study.

Interstellar fishing net

In our own system, Jupiter and the Sun also could act as a “fishing net” that permanently captures interstellar objects, instead of letting them sail through like ‘Oumuamua did. Binary star systems — including Proxima Centauri, our nearest neighboring star — would have an easier time catching interstellar objects, according to Loeb.

But one of the biggest unknowns is still how long a lifeform could survive on an interstellar object. “The lifetime is really critical because it determines how long it can travel from the system it left,” he says. “We don’t have good experimental data.”

Some fraction of microorganisms would likely make it below the object’s icy surface, Loeb says, where they’d be sheltered from radiation. But if they can only survive there for 100,000 years, it would severely restrict panspermia’s prospects. If they could instead survive tens of millions of years, then life would have a decent shot at traveling between stars.

Loeb points out that tardigrades — an eight-legged micro-animal found all over the planet — have endured the vacuum of space, returned to Earth, and still managed to reproduce.

“Even tiny animals are known to be very good astronauts without even a suit,” he says. “Viruses and bacteria may be able to survive much longer.”

Of course, proving life on Earth came from another star would be even more challenging than connecting life here on Earth to Mars. Astronomers discovered the interstellar comet Borisov months before it made its closest pass by Sun in December 2019. However, the alien space rock is traveling at a whopping 93,000 mph. By comparison, Voyager I, one of the fastest probes humans have ever deployed, travels at a relatively pedestrian 38,000 mph.

Humanity’s best hope of catching up with an interstellar interloper would be a cutting-edge probe like the one being developed by Breakthrough Starshot, which would accelerate a tiny craft by beaming lasers at it.

In other words, to prove whether or not life hitchhiked its way to our solar system, we may have to first venture farther out into the stars.