Key Takeaways:

- Betelgeuse, a red supergiant star, will eventually explode as a supernova.

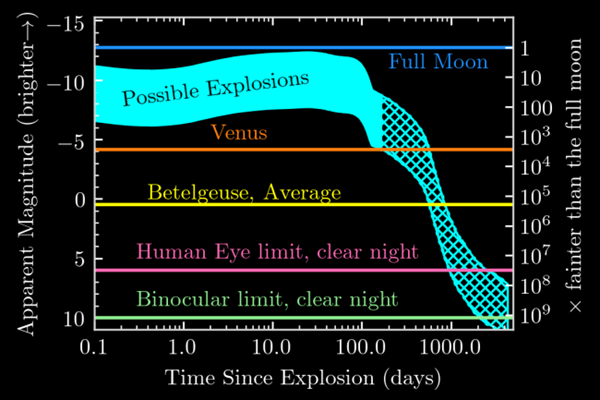

- The supernova will be as bright as a half-moon for over three months, visible even during the day.

- The explosion poses no danger to life on Earth because Betelgeuse is far away.

- Betelgeuse's unusual dimming helps scientists learn about the life cycle of massive stars.

If you stargaze on a clear winter night, it’s hard to miss the constellation Orion the Hunter, with his shield in one arm and the other arm stretched high to the heavens. A bright red dot called Betelgeuse marks Orion’s shoulder, and this star’s strange dimming has captivated skygazers for thousands of years. Aboriginal Australians may have even worked it into their oral histories.

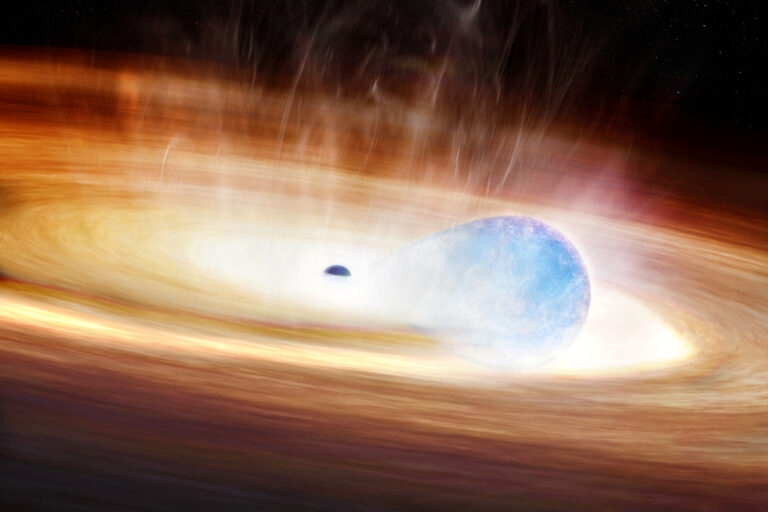

Today, astronomers know that Betelgeuse varies in brightness because it’s a dying, red supergiant star with a diameter some 700 times larger than our Sun. Someday, the star will explode as a supernova and give humanity a celestial show before disappearing from our night sky forever.

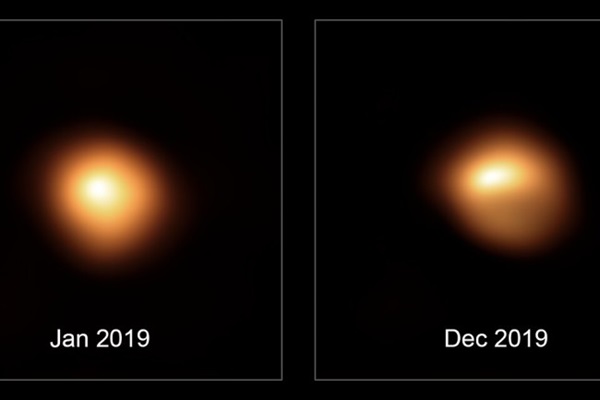

That eventual explosion explains why astronomers got excited when Betelgeuse started dimming dramatically in 2019. The 11th-brightest star dropped in magnitude two-and-a-half-fold. Could Betelgeuse have reached the end of its life? While unlikely, the idea of a supernova appearing in Earth’s skies caught the public’s attention.

And now new simulations are giving astronomers a more precise idea of what humans will see when Betelgeuse does eventually explode sometime in the next 100,000 years.

Supernova seen from Earth

With all the speculation about what a Betelgeuse supernova would look like from Earth, University of California, Santa Barbara, astronomer Andy Howell got tired of the back-of-the-envelope calculations. He put the problem to a pair of UCSB graduate students, Jared Goldberg and Evan Bauer, who created more precise simulations of the star’s dying days.

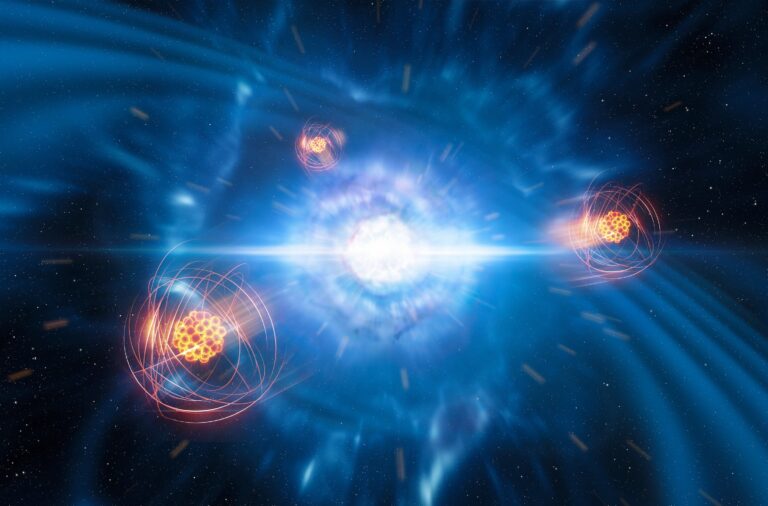

The astronomers say there’s still uncertainty over how the supernova would play out, but they were able to augment their accuracy using observations taken during Supernova 1987A, the closest known star to explode in centuries.

Life on Earth will be unharmed. But that doesn’t mean it will go unnoticed. Goldberg and Bauer found that when Betelgeuse explodes, it will shine as bright as the half-Moon — nine times fainter than the full Moon — for more than three months.

“All this brightness would be concentrated into one point,” Howell says. “So it would be this incredibly intense beacon in the sky that would cast shadows at night, and that you could see during the daytime. Everyone all over the world would be curious about it, because it would be unavoidable.”

Humans would be able to see the supernova in the daytime sky for roughly a year, he says. And it would be visible at night with the naked eye for several years, as the supernova aftermath dims.

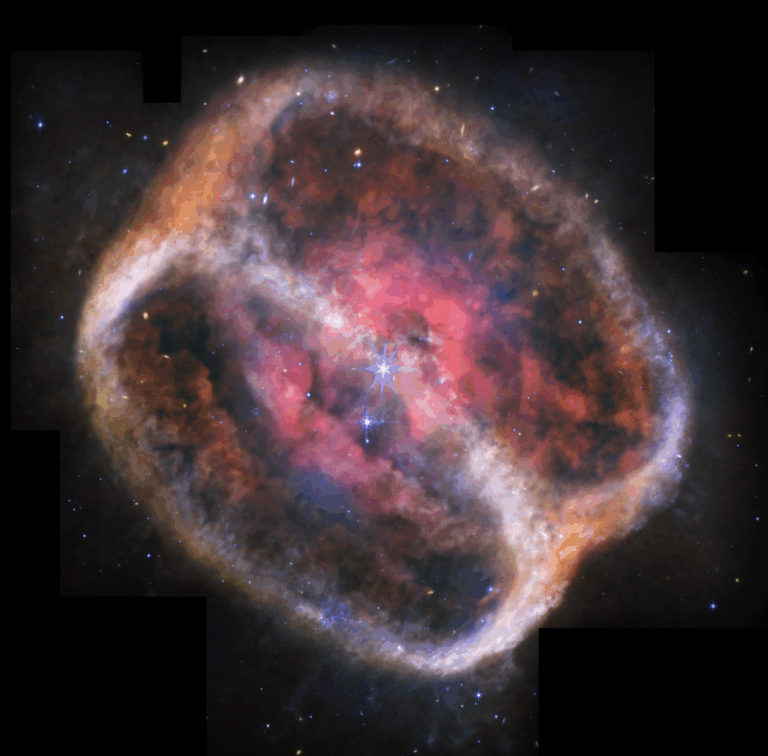

“By the time it fades completely, Orion will be missing its left shoulder,” adds Sarafina Nance, a University of California, Berkeley, graduate student who’s published several studies of Betelgeuse.

The Betelgeuse show

There’s no need to worry about the stellar explosion. A supernova has to happen extremely close to Earth for the radiation to harm life — perhaps as little as several dozen light-years, according to some estimates. Betelgeuse is far outside that range, with recent studies suggesting it sits roughly 724 light-years away, well outside the danger zone.

But the supernova could still impact Earth in some surprising ways. For example, Howell points out that many animals use the Moon for navigation and are confused by artificial lights. Adding a second object as bright as the Moon could be disruptive. It’s not only wildlife that would be disturbed, either; ironically, astronomers themselves would have a hard time.

“Astronomical observations are already difficult when the Moon is bright,” Howell says. “There would be no ‘dark time’ for a while.”

Even studying Betelgeuse would be a unique challenge. The bright light would overwhelm their instruments.

“We couldn’t observe it with most ground-based telescopes, or most in space, either, like Swift or the Hubble Space Telescope,” he adds. Instead, they’d have to modify their telescopes to collect far less light.

And if Betelgeuse does defy the odds and blow up in our lifetimes, astronomers say there will be ample warning. Instruments on Earth would start detecting neutrinos or gravitational waves generated by the explosion as much as a day in advance.

“Imagine a good fraction of the world staying up and staring at Betelgeuse, waiting for the light show to start, and a cheer going up around the planet when it does,” Howell says.

To catch a dying star

But for scientists, Betelgeuse doesn’t have to explode to be interesting. It’s big and bright, making it relatively easy to study.

“It’s fascinating from an astronomer’s perspective because we can study a star that is nearing the end of its life quite closely,” Nance says. “There’s some fascinating physics going on in the internal structure of Betelgeuse.”

Their best guess as to what’s going on right now stems from what astronomers already know about the star and others like it. As Nance explains, that research shows Betelgeuse’s brightness could be changing for a number of reasons. Some astronomers even suspect that several different dimming mechanisms are playing out at once.

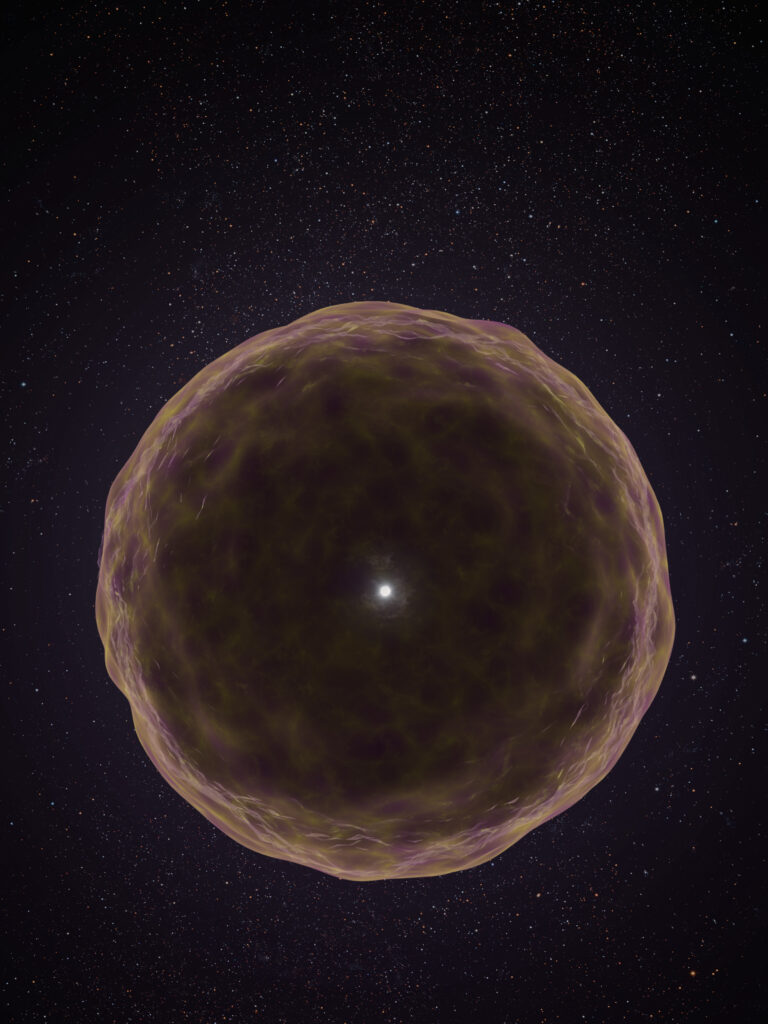

As their nuclear fuel runs out near the ends of their lives, red supergiant stars start to bloat and form growing envelopes of gas and dust. And as this envelope gets bigger, the star’s brightness grows. But that’s not the only way a star like Betelgeuse can dim and brighten. Red supergiant stars also have enormous convective cells on their surfaces — like much larger versions of those on our Sun — where turbulence makes hot material rise from inside the star. Once it reaches the surface, part of that material erupts violently into space like a giant, radioactive belch, which can temporarily change its brightness.

And Betelgeuse’s dimming could even be evidence that it is about to explode. As material erupts from a dying star’s surface, it typically collides, which makes it shine brighter. However, Nance says it’s possible that this material is shrouding the star instead, making it dimmer.

Whatever the root cause, the strange behavior should ultimately offer new insights into the dying days of red supergiant stars. And humanity will have a front-row seat.

“Betelgeuse provides a great setting for astronomers to study these last stages of nuclear burning before it explodes,” Nance says.