Key Takeaways:

The alarm sounded at around 3 a.m. on April 3. An electrical malfunction had stalled the behemoth South Pole Telescope as it mapped radiation left over from the Big Bang. Astronomers Allen Foster and Geoffrey Chen crawled out of bed and got dressed to shield themselves from the –70 degree Fahrenheit temperatures outside. They then trekked a few thousand feet across the ice to restart the telescope.

The Sun set weeks ago in Antarctica. Daylight won’t return for six months. And, yet, life at the bottom of the planet hasn’t changed much — even as the rest of the world has been turned upside-down. The last flight from the region left on Feb. 15, so there’s no need for social distancing. The 42 “winterovers” still work together. They still eat together. They still share the gym. They even play roller hockey most nights.

And that’s why the South Pole Telescope is one of the last large observatories still monitoring the night sky.

An Astronomy magazine tally has found that more than 100 of Earth’s biggest research telescopes have closed in recent weeks due to the COVID-19 pandemic. What started as a trickle of closures in February and early March has become an almost complete shutdown of observational astronomy. And the closures are unlikely to end soon.

Observatory directors say they could be offline for three to six months — or longer. In many cases, resuming operations will mean inventing new ways of working during a pandemic. And that might not be possible for some instruments that require teams of technicians to maintain and operate. As a result, new astronomical discoveries are expected to come to a crawl.

“If everybody in the world stops observing, then we have a gap in our data that you can’t recover,” says astronomer Steven Janowiecki of the McDonald Observatory in Texas. “This will be a period that we in the astronomy community have no data on what happened.”

Yet these short-term losses aren’t astronomers’ main concern.

They’re accustomed to losing telescope time to bad weather, and they’re just as concerned as everyone else about the risks of coronavirus to their loved ones. So, for now, all that most astronomers can do is sit at home and wait for the storm to clear.

“If we have our first bright supernova in hundreds of years, that would be terrible,” says astronomer John Mulchaey, director of the Carnegie Observatories. “But except for really rare events like that, most of the science will be done next year. The universe is 13.7 billion years old. We can wait a few months.”

The prospects get darker when considering the pandemic’s long-term impacts on astronomy. Experts are already worried that lingering damage to the global economy could derail plans for the next decade of cutting-edge astronomical research.

“Yes, there will be a loss of data for six months or so, but the economic impact may be more substantial in the long run,” says Tony Beasley, director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. “It’s going to be hard to build new telescopes as millions of people are out of work. I suspect the largest impact will be the financial nuclear winter that we’re about to live through.”

Asteroids offer clues to the early solar system and the promise of precious resources. That is, assuming they don’t kill us first. To learn more, download our free eBook: Defending Earth from Asteroids.

Closing the windows on the cosmos

Through interviews and email exchanges with dozens of researchers, administrators, press officers and observatory directors, as well as reviewing a private list circulating among scientists, Astronomy magazine has confirmed more than 120 of Earth’s largest telescopes are now closed as a result of COVID-19.

Many of the shutdowns happened in late March, as astronomy-rich states like Arizona, Hawaii and California issued stay-at-home orders. Nine of the 10 largest optical telescopes in North America are now closed. In Chile, an epicenter of observing, the government placed the entire country under a strict lockdown, shuttering dozens of telescopes. Spain and Italy, two European nations with rich astronomical communities — and a large number of COVID-19 infections — closed their observatories weeks ago.

Even many small telescopes have now closed, as all-out shutdowns were ordered on mountaintops ranging from Hawaii’s Mauna Kea to the Chilean Atacama to the Spanish Canary Islands. Science historians say nothing like this has happened in the modern era of astronomy. Even during the chaos of World War II, telescopes kept observing.

As wartime fears gripped Americans in the 1940s, German-born astronomer Walter Baade was placed under virtual house arrest. As a result, he famously declared Mount Wilson Observatory in California to be his official residence. With the lights of Los Angeles dimmed to avoid enemy bombs, Baade operated the world’s largest telescope in isolation, making groundbreaking discoveries about the cosmos. Among them, Baade’s work revealed multiple populations of stars, which led him to realize that the universe was twice as big as previously thought.

In the decades since, astronomers have built ever-larger telescopes to see fainter and farther-off objects. Instruments have become increasingly complex and specialized, often requiring them to be swapped out multiple times in a single night. Enormous telescope mirrors need regular maintenance. All of this means observatory crews sometimes require dozens of people, ranging from engineers and technicians to observers and astronomers. Most researchers also still physically travel to a telescope to observe, taking them to far-flung places. As a result, major observatories can be like small villages, complete with hotel-style accommodations, cooks and medics.

But although observatories might be remote, few can safely operate during a pandemic.

“Most of our telescopes still work in classical mode. We do have some remote options, but the large fraction of our astronomers still go to the telescopes,” says Mulchaey, who also oversees Las Campanas Observatory in Chile and its Magellan Telescopes. “It’s not as automated as you might think.”

‘You don’t know what you missed’

Some of the most complicated scientific instruments on Earth are the gravitational-wave detectors, which pick up almost imperceptible ripples in space-time created when two massive objects merge. In 2015, the first gravitational-wave detection opened up an entirely new way for astronomers to study the universe. And since then, astronomers have confirmed dozens of these events.

The most well-known facilities, the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) — located in Washington state and Louisiana, both pandemic hot spots — closed on March 27. Virgo, their Italian partner observatory, shut down the same day. (It’s also located near the epicenter of that country’s COVID-19 pandemic.)

More than 1,200 scientists from 18 countries are involved with LIGO. And no other instruments are sensitive enough to detect gravitational waves from colliding black holes and neutron stars like LIGO and Virgo can. Fortunately, the observatories were already near the end of the third observing run, which was set to end April 30.

“You don’t know what you missed,” says LIGO spokesperson Patrick Brady, an astrophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “We were detecting a binary black hole collision once a week. So, on average, we missed four. But we don’t know how special they would have been.”

The gravitational-wave detectors will now undergo upgrades that will take them offline through at least late 2021 or early 2022. But the pandemic has already delayed preliminary testing for their planned fourth run. And it could prevent future work or even disrupt supply chains, Brady says. So, although it’s still too early to know for sure, astronomy will likely have to wait a couple of years for new gravitational-wave discoveries.

Then there’s the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). Last year, the EHT collaboration released the first-ever image of a black hole. And on April 7, they published another unprecedented image that stares down a black hole’s jet in a galaxy located some 5 billion light-years away. But now, EHT has cancelled its entire observing run for the year — it can only collect data in March and April — due to closures at its partner instruments.

Around the world, only a handful of large optical telescopes remain open.

The Green Bank Observatory, Earth’s largest steerable radio telescope, is still searching for extraterrestrial intelligence, observing everything from galaxies to gas clouds.

The twin Pan-STARRS telescopes on the summit of Hawaii’s Haleakala volcano are still scouting the sky for dangerous incoming asteroids. Both instruments can run without having multiple humans in the same building.

“We are an essential service, funded by NASA, to help protect the Earth from (an) asteroid impact,” says Ken Chambers, director of the Pan-STARRS Observatories in Hawaii. “We will continue that mission as long as we can do so without putting people or equipment at risk.”

The last of large telescopes left open

With observatory domes closed at the world’s newest and best telescopes, a smattering of older, less high-tech instruments are now Earth’s largest operating observatories.

Sporting a relatively modest 6-meter mirror, the biggest optical telescope still working in the Eastern Hemisphere is Russia’s 45-year-old Bolshoi Azimuthal Telescope in the Caucasus Mountains, a spokesperson there confirmed.

And, for the foreseeable future, the largest optical telescope on the planet is now the 10-meter Hobby-Eberly Telescope (HET) at McDonald Observatory in rural West Texas. Astronomers managed to keep the nearly-25-year-old telescope open thanks to a special research exemption and drastic changes to their operating procedures.

To reduce exposure, just one observer sits in HET’s control room. One person turns things on. And one person swaps instruments multiple times each night, as the telescope switches from observing exoplanets with its Habitable Zone Finder to studying dark energy using its now-poorly-named VIRUS spectrograph. Anyone who doesn’t have to be on site now works from home.

“We don’t have the world’s best observatory site. We’re not on Mauna Kea or anything as spectacular,” says Janowiecki, the HET’s science operations manager. “We don’t have any of the expensive adaptive optics. We don’t even have a 2-axis telescope. That was [intended as] a massive cost savings.”

But, he added, “In this one rare instance, it’s a strength.”

The supervising astronomer of HET now manages Earth’s current largest telescope from a few old computer monitors he found in storage and set up on a foldout card table in his West Texas guest bedroom.

Like the Hobby-Eberly Telescope, the handful of remaining observatories run on skeleton crews or are entirely robotic. And all of the telescope managers interviewed for this story emphasized that even if they’re open now, they won’t be able to perform repairs if something breaks, making it unclear how long they could continue operating in the current environment.

‘We will miss some objects’

The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) utilizes the robotic, 48-inch Samual Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory in Southern California to produce nightly maps of the northern sky. And, thanks to automation, it remains open.

The so-called “discovery engine” searches for new supernovas and other momentary events thanks to computers back at Caltech that compare each new map with the old ones. When the software finds something, it triggers an automatic alert to telescopes around the world. Last week, it sent out notifications on multiple potentially new supernovas.

Similarly, the telescopes that make up the Catalina Sky Survey, based at Arizona’s Mount Lemmon, are still searching the heavens for asteroids. In just the past week, they found more than 50 near-Earth asteroids — none of them dangerous.

Another small group of robotic telescopes, the international Las Cumbres Observatory network, has likewise managed to stay open, albeit with fewer sites than before. In recent weeks, their telescopes have followed up on unexpected astronomical events ranging from asteroids to supernovas.

“We are fortunate to still be keeping an eye on potential new discoveries,” says Las Cumbres Observatory director Lisa Storrie-Lombardi.

But, overall, there are just fewer telescopes available to catch and confirm new objects that appear in our night sky, which means fewer discoveries will be made.

Chambers, the Pan-STARRS telescope director, says his team has been forced to do their own follow-ups as they find new asteroids and supernovas. “This will mean we make fewer discoveries, and that we will miss some objects that we would have found in normal times,” he says.

‘It’s stressing them out’

Astronomer Cristina Thomas of Northern Arizona University studies asteroids. She was the last observer to use the 4.3-meter Lowell Discovery Telescope before it closed March 31 under Arizona’s stay-at-home order.

Thomas warns that, in the short term, graduate students could bear the brunt of the lost science. Veteran astronomers typically have a backlog of data just waiting for them to analyze. But Ph.D. students are often starved for data they need to collect in order to graduate on time.

“It’s stressing them out in a way that it doesn’t for me. We’re used to building in a night or so for clouds,” Thomas says. “If this goes on for months, this could put [graduate students] pretty far behind.”

One of Thomas’ students was set to have observations collected for their dissertation by SOFIA, NASA’s airborne observatory. But the flying telescope is currently grounded in California, leaving it unclear when the student will be able to complete their research. And even when astronomy picks back up, everyone will be reapplying for telescope time at once.

But the damage isn’t only limited to graduate students. An extended period of observatory downtime could also have an impact on Thomas’ own research. Later this year, she’s scheduled to observe Didymos, a binary asteroid that NASA plans to visit in 2021. Those observations are supposed to help chart the course of the mission.

“The big question for us is: ‘When are we going to be able to observe again?’” Thomas says. “If it’s a few months, we’ll be able to get back to normal. If it ends up being much longer, we’re going to start missing major opportunities.”

Can’t just flip a switch

The same qualities that brought observational astronomy to a standstill in the era of social distancing will also make it tough to turn the telescopes back on until the pandemic has completely passed. So, even after the stay-at-home orders lift, some observatories may not find it safe to resume regular operations. They’ll have to find new ways to work as a team in tight spaces.

“We are just starting to think about these problems now ourselves,” says Caltech Optical Observatories deputy director Andy Boden, who also helps allocate observing time on the Keck Observatory telescopes in Hawaii. “There are aspects of telescope operations that really do put people in shared spaces, and that’s going to be a difficult problem to deal with as we come out of our current orders.”

Astronomers say they’re confident they can find solutions. But it will take time. Tony Beasley, the NRAO director, says his team is already working around a long list of what they’re now calling “VSDs,” or violation of social distancing problems. Their workarounds are typically finding ways to have one person do something that an entire team used to do.

Beasley’s research center operates the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, as well as the Very Large Array in New Mexico and the global Very Long Baseline Array — all of which are still observing, thanks to remote operations and a reimagined workflow.

Although the new workflow is not as efficient as it was in the past, so far there haven’t been any problems that couldn’t be solved. However, Beasley says some work eventually may require the use of personal protective equipment for people who must work in the same room. And he says they can’t ethically use such gear while hospitals are in short supply.

But Beasley and others think interesting and valuable lessons could still come out of the catastrophe.

“There’s always been kind of a sense that you had to be in the building, and you’ve got to stare the other people down in the meeting,” he says. “In the space of a month, I think everyone is surprised at how effective they can be remotely. As we get better at this over the next six months or something, I think there will be parts where we won’t go back to some of the work processes from before.”

Modern-day cathedrals

Despite best efforts and optimistic outlooks, some things will remain outside astronomers’ control.

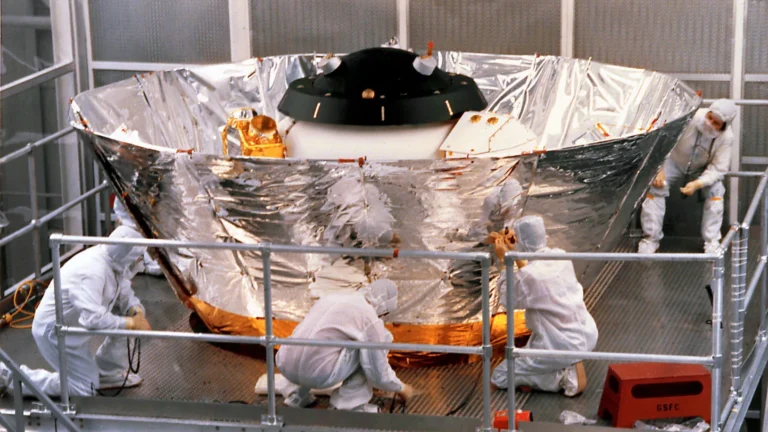

Right now, researchers are completing the 2020 Astronomy and Astrophysics Decadal Survey, a kind of scientific census. The guiding document sets priorities and recommends where money should be spent over the next 10 years. NASA and Congress take its recommendations to heart when deciding which projects get funded. Until recent weeks, the economy had been strong and astronomers had hoped for a decade of new robotic explorers, larger telescopes, and getting serious about defending Earth from asteroids.

“Many of NASA’s most important activities — from Mars exploration to studying extrasolar planets to understanding the cosmos — are centuries-long projects, the modern version of the construction of the great medieval cathedrals,” Princeton University astrophysicist David Spergel told the website SpaceNews.com last year as the process got underway. “The decadal surveys provide blueprints for constructing these cathedrals, and NASA science has thrived by being guided by these plans.”

However, many experts are predicting the COVID-19 pandemic will send the U.S. into a recession; some economists say job losses could rival those seen during the Great Depression.

If that happens, policymakers could cut the funding needed to construct these cathedrals of modern science — even after a crisis has us calling on scientists to save society.