As the COVID-19 crisis continues around the planet, humanity’s gaze is firmly fixed on the pandemic playing out around us. Meanwhile, more than 100 of Earth’s largest research telescopes have been forced to shutter their doors, Astronomy magazine reported this week.

It’s the perfect time for an asteroid to strike, many space fans deadpanned in reply.

But there’s no need to worry about an incoming asteroid — at least, not any more than usual. Despite the closures, Earth’s top asteroid-hunting instruments remain on the prowl for potentially deadly space rocks.

NASA funds most major asteroid-hunting efforts. The space agency has a congressional mandate to find some 90 percent of near-Earth objects (NEOs) larger than 460 feet (140 meters) across. As the name implies, NEOs are comets and asteroids that get a little too close for comfort.

Asteroids offer clues to the early solar system and the promise of precious resources. That is, assuming they don’t kill us first. To learn more, download our free eBook: Defending Earth from Asteroids.

The workhorse instruments in that effort are the twin Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) telescopes in Hawaii, as well as the three Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) telescopes in Arizona. And both of those efforts continue. NEOWISE, a NASA space telescope repurposed to hunt for near-Earth objects, is also still operating.

“We are an essential service, funded by NASA, to help protect the Earth from [an] asteroid impact,” says Ken Chambers, director of the Pan-STARRS Observatories in Hawaii. “We will continue that mission as long as we can do so without putting people or equipment at risk.”

Dozens of asteroids in a night

Pan-STARRS1 and Pan-STARRS2 are modest (1.8-meter), nearly identical telescopes perched atop the summit of Haleakala on the island of Maui. These modern marvels use wide-angle views and the largest digital cameras on Earth (1,400 megapixels) to map the heavens night after night. Each image is compared to an existing catalog, revealing the faint movements of light from previously undetected asteroids.

The Catalina Sky Survey works similarly. It has two detection telescopes on Mount Lemmon in southern Arizona, plus one more that’s used for following up on new finds. On any given night, CSS has a good chance of detecting a new NEO. And sometimes, it finds dozens in a single night. Recently, astronomers used CSS to discover that Earth has a new mini-moon. (Although that mini-moon may already be gone.)

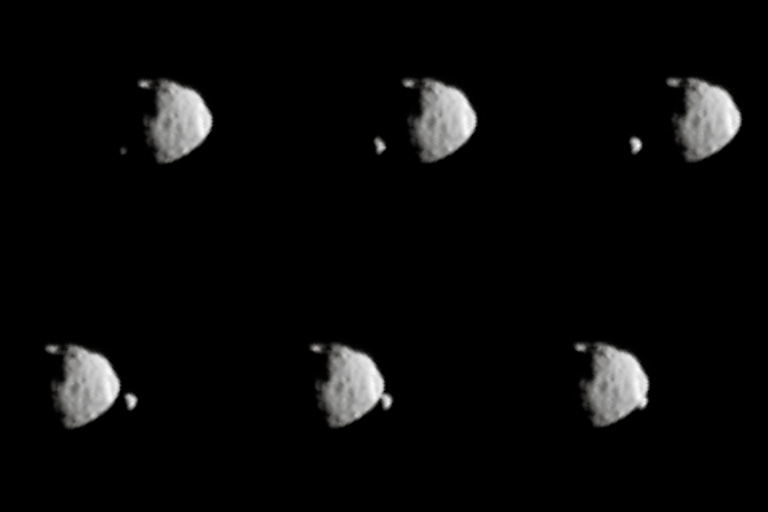

Detecting potentially hazardous space rocks is obviously step one, but follow-up is also an extremely vital aspect of NEO discovery. It’s hard to characterize an asteroid’s size, composition and orbit without collecting several observations of the object over the course of multiple nights. Just one-third of new NEO finds are eventually confirmed.

“Each NEO candidate must be treated as if it were a potential impactor, until impact solutions can be ruled out,” says Eric Christensen, head of the Catalina Sky Survey.

In normal times, astronomers send new NEO entries to the Minor Planet Center, and observers worldwide then take additional observations to refine the objects’ trajectories. Previously, this has let researchers track small, Earth-approaching asteroids until they harmlessly break up in our atmosphere, sometimes allowing scientists to recover fragments that reach the ground.

Following up on new asteroids

But with most telescopes closed, there are fewer instruments left to confirm and collect details on new discoveries. As a result, the Catalina Sky Survey and Pan-STARRS have both been forced to tackle more of their own follow-up work. In recent weeks, they’ve had to double back so often that it’s reducing their ability to make new discoveries.

One group that is still following up on new discoveries is the Las Cumbres Observatory global network, which has managed to keep several of its telescopes up and running. But even many small, robotic telescopes have had to close as their mountaintop sites are put on lockdown.

“Several of the most prolific follow-up sites — in Arizona, Chile, and elsewhere — have unfortunately had to cease operations due to COVID-19 concerns,” Christensen says. “This has shifted more of the follow-up burden back to the survey programs.”

Chambers, the Pan-STARRS director, agrees. “We are adapting our observing strategy to do more self-follow-up,” he says. “This will mean we make fewer discoveries and that we will miss some objects that we would have found in normal times.”

The other long-term problem is that social distancing restrictions have stopped maintenance work. The Pan-STARRS telescopes, for instance, will only be able to operate as long as the equipment continues to function properly.

Similarly, if a staff member comes down with COVID-19, the telescopes will be shut down. So, to avoid bringing things to a grinding halt, no two members of the Pan-STARRS team are allowed in the same building at the same time.

“To protect either people or equipment, we may need to cease operations at any time,” Chambers said.

The asteroid threat

Contrary to headlines in tabloid news, Earth’s chances of getting hit by a large asteroid are very slim at any given time.

Even the small, so-called “city killer” asteroids — those spanning a couple hundred feet across — probably only reach Earth roughly once every few centuries. And because most of our world is covered in water, they’re unlikely to actually hit a city, despite the name.

The last known such event happened in Tunguska, Siberia, in 1908. A roughly 120-foot-wide (36.5 m) space rock entered Earth’s atmosphere at a blistering speed of 33,000 mph (53,100 km/h). The resulting friction heated it to tens of thousands of degrees Fahrenheit. And this, combined with intense pressure, ultimately caused the rock to dramatically explode some 5 miles (8 kilometers) above the ground. The blast, which is estimated to have released as much energy as almost 200 Hiroshima bombs, flattened trees on the ground over an area of roughly 800 square miles (2,100 square kilometers). Some sources suggest that as many as three people died.

Earth got relatively lucky with Tunguska, but that doesn’t mean asteroids aren’t still a major risk to our planet. In 2013, a space rock the size of a house exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, injuring more than 1,000 people as a powerful shock wave blew out countless windows, sending out shards of glass and debris. And just last year, one of these “city killer” asteroids, dubbed 2019 OK, actually passed between Earth and the Moon without astronomers noticing until just before it happened.

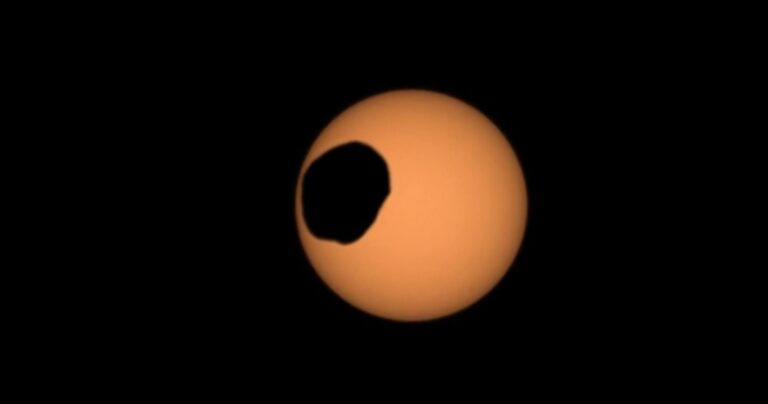

The asteroid caught astronomers by surprise because it approached from the direction of the Sun. And, like a baseball player squinting to locate a fly ball on a cloudless day, astronomers struggle to see small, relatively faint objects with our home star in the background.

Earth will get hit with a major asteroid again, it’s just a question of when.And that’s why astronomers think it’s important to keep a constant watch, even during a pandemic.

Fortunately, there’s only a slim chance humanity will have to face two global crises at once. And that’s something we can all be happy about right now.