In 1977, NASA launched the twin Voyager spacecraft to probe the outer reaches of our solar system. The space agency was still in its infancy then. But with the triumph of the Apollo Moon landings just five years behind them, NASA was ready to dive headfirst into another bold idea.

Thanks to a rare alignment of the solar system’s four outer planets — which happens just once every 175 years — the agency had the chance to redefine astronomy by exploring Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune in one fell swoop.

The scheme was a stunning success.

At Jupiter, the probes surprised scientists when they spotted volcanoes on the moon Io and discovered Europa is likely an ocean world. Saturn surrendered its atmospheric composition and new rings. And Voyager 2 returned humanity’s only close-up looks at Uranus and Neptune. To this day, scientists are still making new discoveries by exploring Voyager’s decades-old data.

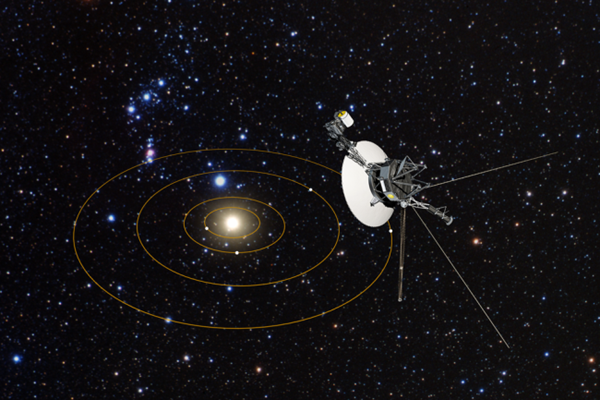

But these probes haven’t stopped scouting the outer solar system. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still functioning today, making them the longest-running and most-distant space mission in history. Though they are each taking different paths, both spacecraft are still screaming their way out of the solar system. And they still have a long way to go.

Where are the Voyager Probes Going?

Even traveling at 35,000 mph, the Voyager probes will need another 300 years just to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud — a large sphere of icy space rocks that begins a couple of thousand times farther from the Sun than Earth. The outer edge of the Oort Cloud may be so distant that it take the Voyager probes 30,000 years or more to completely cross it, according to NASA.

After that, in about 40,000 years, Voyager 1 could finally approach another star. Voyager 2, however, will need 300,000 years before it comes close to bathing in the light of another star.

Thankfully, we don’t have to wait that long for new discoveries. Both probes are still making fascinating finds along the way.

What is the Voyager Mission Studying?

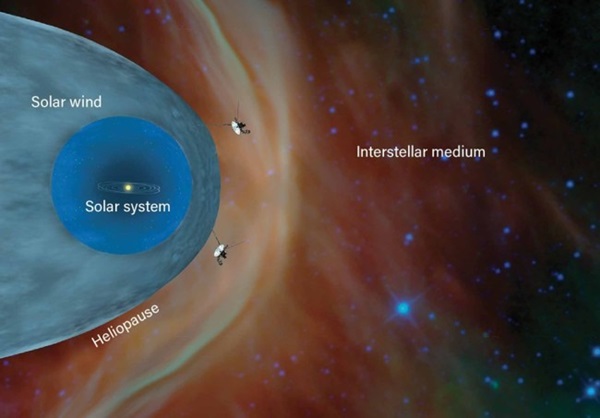

Back in 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to reach interstellar space. There are no road signs letting NASA know that the craft broke the barrier. Instead, they determined it thanks to measurable changes Voyager 1 detected when it hit a region called the heliopause.

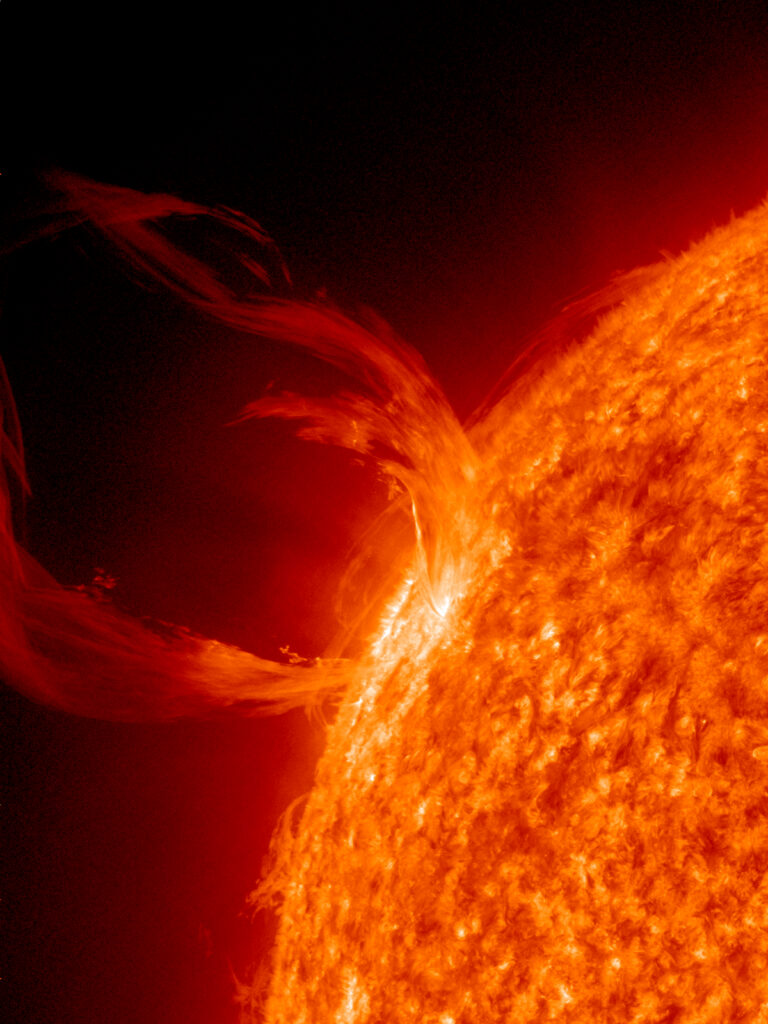

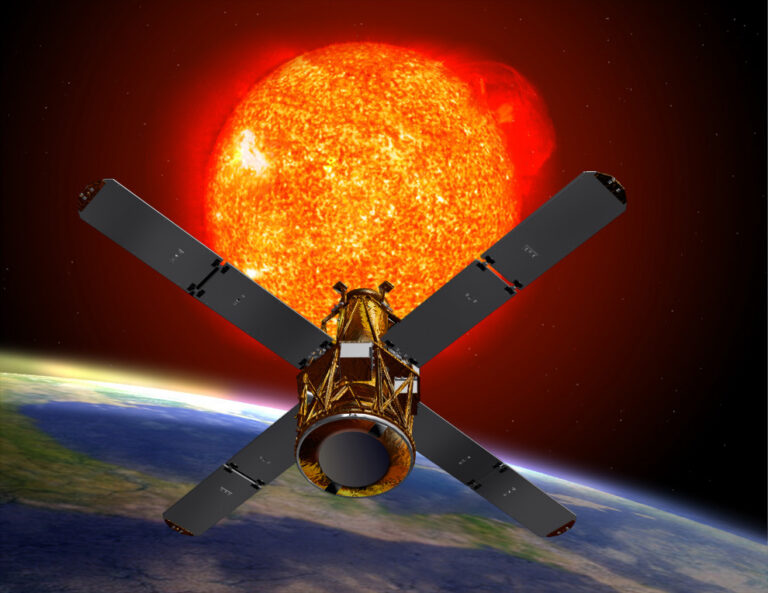

Our Sun produces an intense stream of particles, dubbed the solar wind, that flows outward in all directions and creates a magnetic field that shields the planets from interstellar particles. The powerful wind carves a huge cavity in the interstellar medium (the region between stars) that encapsulates all the planets. This protective bubble is called the heliosphere, and the heliopause is its outer boundary — where our Sun’s influence is finally overpowered by distant activity like erupting supernovas.

Scientists were surprised when Voyager 1 measured the magnetic field just inside and just outside of the heliopause, finding no significant changes in its overall direction. Then, when Voyager 2 reached this same boundary of interstellar space in 2018, it found similar results.

But Voyager 2 offered up another surprise when NASA scientists released its first results from beyond the heliopause. They had originally expected that particles from our sun would not “leak out” of the heliosphere into interstellar space. And Voyager 1 saw no such leakage. But Voyager 2 found the opposite. It recorded a small trickle of solar particles streaming through the heliopause.

In recent years, the twin probes also have discovered that the solar wind moves more slowly at our solar system’s edge than expected. All said, by studying data from the two probes, astronomers have been able to compare, contrast and confirm results about the boundary that separates our solar system from interstellar space.

When Will Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 Die?

Since their launch more than 40 years ago, NASA has remained in near-constant contact with the Voyager probes. However, the space agency has temporarily stopped receiving messages from Voyager 2 while they work to repair and update one of the three Deep Space Network antennas used to communicate with the probes, The New York Times reported in March.

It’s a risky move, and there’s a chance we may not hear from Voyager 2 once the receivers are turned back on. But Earth is still in contact with Voyager 1. And the discoveries haven’t ended quite yet. Mission planners intend to keep communicating with the spacecraft until they fail or lose power.

Both should be able to keep at least one scientific instrument running until 2025. And even after that, NASA expects to continue receiving engineering data from the probes until 2035, when they exceed the range of the Deep Space Network antennas.

Sadly, that means the so-called interstellar mission won’t be able to tell us what they see once they reach the stars.

A Golden Record of the Journey

Of course, NASA knew this day would come long before the missions launched. And this lonesome, one-way ticket out of the solar system was more than some astronomers could resist. Carl Sagan was so drawn to the idea that he helped NASA create an entire cultural component for the mission, lest some future aliens — or spacefaring earthlings — found one of the Voyager probes.

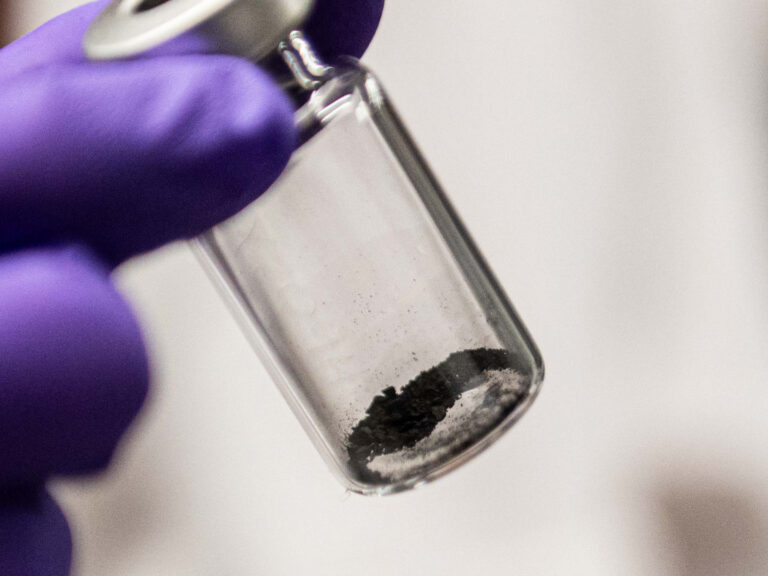

Each spacecraft carries a golden record that serves as a time capsule from Earth, with their contents chosen by a committee led by Sagan. These messages to the stars contain sights and sounds from Earth, as well as music from dozens of countries and greetings spoken in 55 languages from around the world.

So, while someday we’ll stop hearing back from the Voyager probes, it might not be the last message conveyed on their journey to the stars.

“Billions of years from now, our Sun, then a distended red giant star, will have reduced Earth to a charred cinder,” Sagan opined. “But the Voyager record will still be largely intact, in some other remote region of the Milky Way galaxy, preserving a murmur of an ancient civilization that once flourished — perhaps before moving on to greater deeds and other worlds — on the distant planet Earth.”