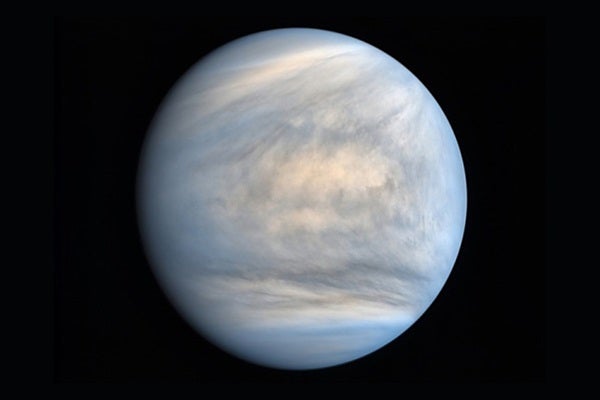

Venus is a planet defined by its clouds. The world’s thick, reflective envelope not only whips around the planet at breakneck speeds, but also helps our nearest neighbor shine brighter than any object in the night sky besides the Moon. Unfortunately, these bizarre clouds simultaneously block our view of the venusian surface.

But things weren’t always that way.

If you visited the early solar system, Venus and Earth would have seemed to be on similar paths. They were nearly identical in both size and water content. But eventually, Venus lost its oceans. This rapidly transformed the planet into a hellscape filled with volcanoes that belched carbon dioxide — and without oceans, the planet had no way to absorb and store the heat-trapping gas.

Scientists know the basics. But despite centuries of study, Venus’ clouds remain shrouded in mystery. Why did Venus lose its water? Is there life in Venus’ clouds? And will humans ever be able to travel there?

Where did Venus’ oceans go?

Around 4 billion years ago, Venus and Earth were both ocean worlds. Then, water started evaporating from our sister planet’s surface. Over time, this led to an increase in heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, ultimately resulting in a runaway greenhouse effect.

Fast-forward to today and the venusian atmosphere is unbelievably dry (Earth sports about 100,000 times more water). But scientists still aren’t sure exactly what triggered Venus to lose its water in the first place.

They don’t think it’s because Venus is closer than Earth to the Sun. But it could be because Venus lacks a magnetic field to protect it from be the solar wind, which is an intense stream of high-energy particles flowing from the Sun. Unlike Earth, Venus only rotates once every roughly 243 days, so it largely lacks the internal convection found in our planet. This effectively robs Venus of a magnetic shield, which past missions have shown allows the solar wind to whisk water from Venus’ atmosphere and carry it out into space.

Nonetheless, astronomers are eager for more close-up observations that might better explain the history of Venus’ missing oceans.

Venus as an analogue for Earth’s climate change

In the 1970s, astronomers began to realize that Venus was so Mordor-esque largely because it has carbon dioxide (CO2) levels hundreds of times higher than Earth’s. (On Earth, the heat-trapping gas only accounts for a tiny — yet growing — portion of our atmosphere: just over 400 parts per million.) At the same time, scientists were realizing that rising CO2 levels on Earth could likewise cause our planet to get warmer.

This turned the discovery of a global greenhouse effect on Venus into a warning for what could happen to us here on Earth. And in the decades since, scientists have kept looking to Venus to help explain and predict how our own climate will change as the CO2 in our atmosphere continues to rise.

Life in Venus’ clouds

In the 1960s, Carl Sagan suggested that alien life might be hiding in the clouds of Venus. According to research, mysterious dark patches — called “unknown absorbers” — soak up large amounts of UV solar radiation, which scientists think could serve as a fuel for life.

And thanks to recent observations, scientists have found some strange evidence that indicates Sagan could be right. These patches seem to be driving weather patterns in hard-to-explain ways. Some scientists say the particles that make up the dark patches within the clouds could even resemble microorganisms in our own atmosphere.

Venus’ strange, ‘super-rotating’ clouds

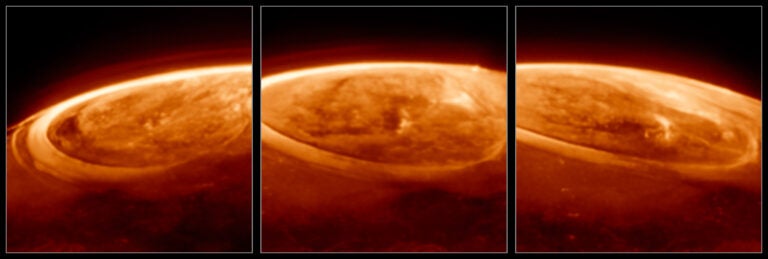

One of the biggest lingering mysteries related to our sister planet is why its clouds circle at such an incredible speed. Venus’ upper atmosphere whips around the world every four Earth days. Yet a day on Venus (one full rotation of the planet) lasts 243 Earth days.

When an atmosphere spins faster than the planet’s surface, astronomers call the phenomenon super-rotation. And, incredibly, Venus’ highest-altitude winds are getting more super over time — though the wind speeds aren’t always consistent. The European Space Agency’s Venus Express mission found that, sometimes, Venus’ clouds could take less than four days to circle the planet, while other times they needed more than five days to complete a single trip.

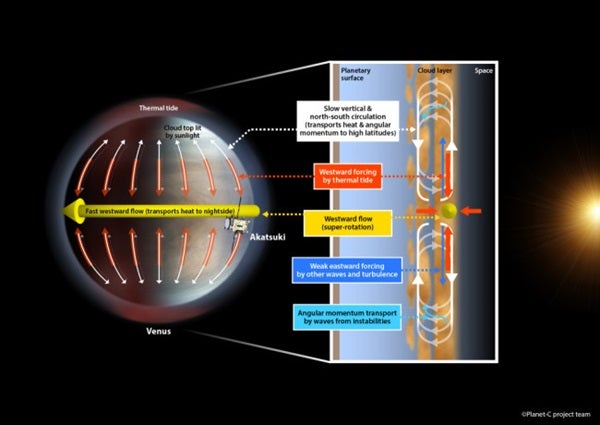

In a study published in April 2020, the Japanese space agency’s Akatsuki spacecraft found that Venus’ super-rotation is fueled by a combination of causes, including thermal tides from the Sun’s heat, turbulence in the atmosphere and planetary waves driven by the world’s rotation.

Missions to Venus’ atmosphere

Space agencies have never kept a spacecraft alive on Venus’ surface for more than 127 minutes, which was accomplished by the Soviets’ Venera 13. Temperatures on the ground are hot enough to melt lead, tin and zinc; the atmospheric pressure would be like diving more than half a mile below the ocean’s surface on Earth. But we don’t necessarily have to reach the planet’s surface; we can still learn a lot about our mysterious neighbor by merely getting close.

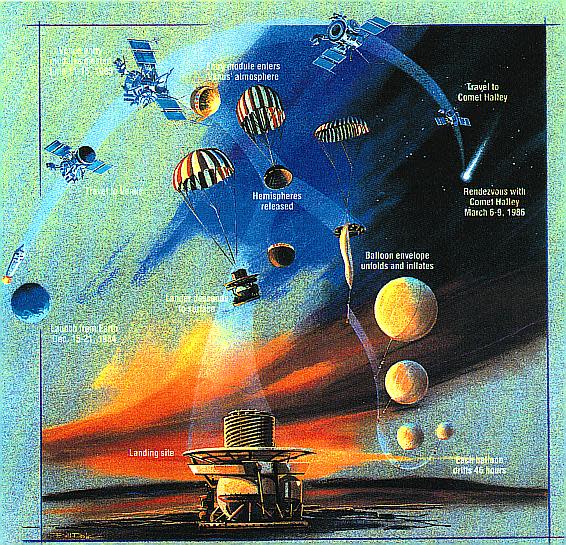

The Soviet Union proved the concept in 1985, when it successfully deployed two helium balloons, Vega I and Vega II, into Venus’ clouds. Carried by hurricane-force winds, the spacecraft traveled some 7,150 miles from the planet’s nightside to its dayside over the course of roughly two Earth days. Then, their batteries died. But despite their still relatively short lifespans, Vega I and II revealed just how fast Venus’ clouds travel, measuring speeds in excess of 150 mph.

A handful of similar missions are now being considered for launch in the coming decade. Northrop Grumman wants NASA to greenlight a spacecraft it calls the Venus Atmospheric Maneuverable Platform, which would travel around the clouds looking for signs of alien life. And India has funded early work on its Shukrayaan-1 Venus mission, which could include a balloon to study cloud chemistry.

But Venus’ atmosphere could prove to be a safe place to study the surface, too. Some scientists have even suggested using balloons on Venus that could detect quakes below.

Can we colonize Venus?

In the Star Wars universe, Lando Calrissian runs Cloud City, a mining colony hovering at just the right height in the clouds of a gaseous planet so that its inhabitants can walk outside without a spacesuit. Some scientists have viewed Venus in a similar way.

“At cloud-top level, Venus is the paradise planet,” NASA scientist Geoffrey Landis wrote in research published in 2003.

If you traveled to the cloud layers some 30 miles above Venus’ surface, you’d experience a surprisingly Earth-like temperature and a comfortable atmospheric pressure. You wouldn’t want to linger completely unprotected in Venus’ atmosphere, but it makes for a compelling settlement site for a cloud city.

In fact, other than Earth itself, Venus’ clouds are the most habitable environment in the solar system, Landis found. That’s led science fiction writers — and a few scientists — to fantasize about building a colony there.

Most ideas about how to accomplish such a feat rely on structurally reinforced blimps filled with breathable air — which floats on Venus — that would suspend platforms high above the world’s hellish surface.

One such proposal from NASA, the High Altitude Venus Operational Concept, would use a series of missions to prove the concept is possible before ultimately dropping astronauts into Venus’ atmosphere in an inflatable airship. There, traveling at the speed of the surrounding clouds, the astronauts would put Jules Vernes’ Around the World in 80 Days to shame with a colony that circled the planet in less than a week.