On August 10, 1888, at around 8:30 p.m., a bright fireball lit up the skies above a mountain village in the Kurdistan Region near modern-day Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. The fireball carried a trail of “smoke” as it passed toward a neighboring village. Then, it exploded overhead, leveling crops and raining stones for 10 minutes on a “pyramid-shaped” hill below. The falling debris killed one man and paralyzed another.

A group of scientists, two in Turkey and one in the U.S., recently found this account in newly digitized archives of the Ottoman Empire. The caliphate, which ruled large parts of Europe, Asia and Africa between the 14th and 20th centuries, was known for keeping meticulous records. And the documents’ recent digitization makes them more accessible than ever. The researchers published their findings April 22 in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

Rediscovering an ancient accident

To uncover this dramatic death by meteorite, planetary scientist Ozan Unsalan of Ege University in Turkey says he and his colleagues had been continuously searching the new archives for a number of translated keywords like “meteorite,” “fireball,” “stones from the sky,” and more. Out of millions of documents, they got 10 hits. Three of those documents are letters about this event. The other papers cover several additional, yet-to-be-published tales of potential meteorite strikes.

Asteroids offer clues to the early solar system and the promise of precious resources. That is, assuming they don’t kill us first. To learn more, download our free eBook: Defending Earth from Asteroids.

The accounts of the 1888 event are compelling because they were written by local high-ranking officials, including the regional governor, and forwarded to the sultan. Furthermore, they suggest that stony fragments were recovered from the impact site and mailed in to the central government. Unsalan and his team have looked for the would-be meteorites in area museums and archives, but have so far come up empty-handed. Those potential space rocks could be lost in a museum collection now.

The authors say this is the oldest known meteorite death in recorded history because no other purported incident can claim to have both a trustworthy historical record and a sample fragment from the site. However, it’s important to reiterate that the researchers have not been able to recover or confirm that the stony fragments supposedly collected after the 1888 event were, in fact, of extraterrestrial origin.

Historical Claims of Death by Meteorite

However, history is surprisingly rich with accounts of people killed by meteorites. For decades, researchers have searched for and debated historical claims of people and animals that might have died in impacts.

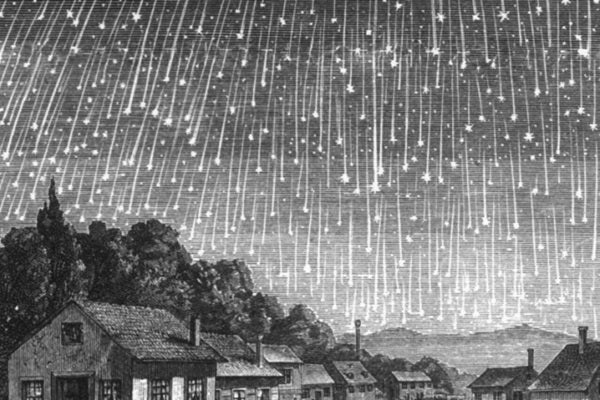

For example, on September 14, 1511, a monk and several animals were said to have been killed in Lombardy, Italy, after more than 100 pounds of space rocks fell. And Chinese records say that 10 people were killed by a large shooting star that fell on a rebel camp on January 14, 616.

Back then, people didn’t really know what meteorites were. But by the early 1800s, the scientific community generally agreed that meteorites fell from space. And there have been many accounts since then — often potentially dubious in nature — of people being killed by space rocks.

In 2016, a bus driver who was walking near a college in India was killed and three others were hurt when a supposed space rock smashed down and exploded. The Indian government and even some researchers backed the claim, and global mainstream news outlets carried the story. But those claims died down after a story in The New York Times said NASA disputed that the explosion was a meteorite. However, NASA never actually analyzed the event, and it’s not clear that any scientific investigation was ever published.

First confirmed meteorite death?

Surprisingly, though, there’s never been a proven death by meteorite, despite widespread acceptance that it has probably happened before. Absolute proof is hard to find. Perhaps the closest confirmation in history is the famous Tunguska event in Siberia in 1908, in which historical accounts suggest at least one person was killed by an airburst. But scientists never found fragments from the exploded space rock, so nobody ever studied the meteoritic material that rained down.

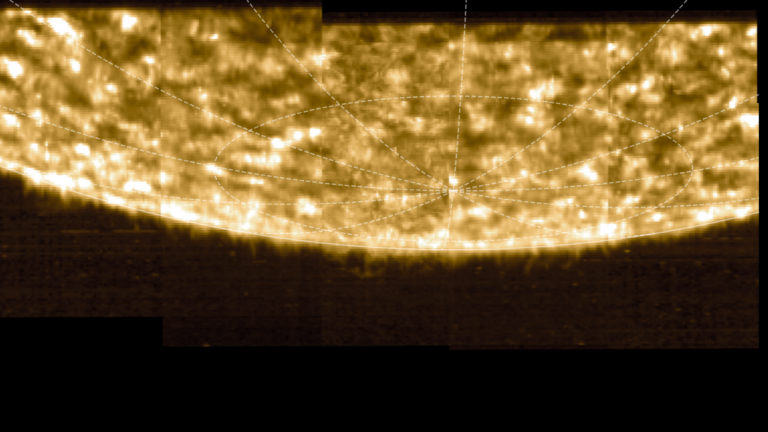

Earth had another close call more recently. In 2013, some 1,200 people were injured during an air blast over Chelyabinsk, Russia. The event, widely recorded on dashcams and surveillance cameras, seems strikingly similar to the one depicted in the Ottoman Empire accounts. In Russia, a 60-foot (18 meter) asteroid entered Earth’s atmosphere at about 40,000 miles per hour (64,400 kph). The intense heat and pressure it faced while barreling through our atmosphere caused it to explode as a superbolide meteor, or a giant fireball.

The resulting shock wave — which lagged well behind the bright visual burst, giving people plenty of time to look up — blasted out windows across the city, scattering dangerous debris. The concussive wave was even powerful enough to punch a large hole in a frozen lake. Most people faced lacerations from flying glass; one man had a serious back injury from being thrown to the ground. But, fortunately, no one was killed.

Physicist Mark Boslough is an expert in meteor fireballs and was one of the first Western scientists to arrive after the Chelyabinsk event in 2013. He wasn’t involved in the latest research about the 1888 event, but admits the researchers have a “compelling story,” albeit one without physical evidence.

“I would not use the word ‘proof,’” he said, adding “It will be very exciting if this historical research leads to meteorite discoveries.”

NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer, Lindley Johnson, who was also not involved in the new research, said he was intrigued by the study. “I found their story to be credible to the extent it can be so many years after the fact,” Johnson said. “Finding a meteorite sample would certainly cinch it.”

And, this time, the researchers do have a reasonable shot at finding that direct proof, if it does exist. The team plans to next mount an expedition to Iraq to find any evidence that still may be hiding on the ground.

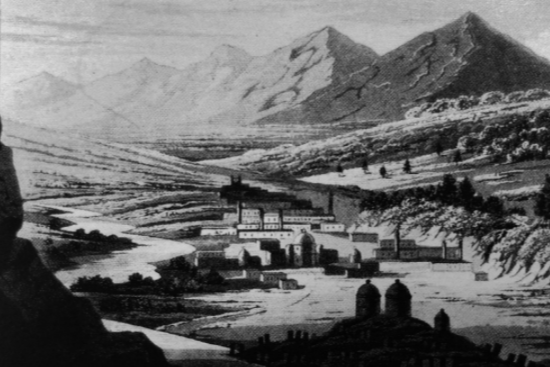

They know the general area. And while the exact villages mentioned in the texts have either been renamed or no longer exist, the accounts do say the meteorites fell in a range of pyramid-shaped hills. In their searches of the same Ottoman Empire archives, the scientists actually found a drawing of a small mountain range in the area from the early 1900s that shows pyramid-shaped hills that seem to match that description.

“We hope to find the exact impact site after these hard days are passed, with the hope of finding some samples maybe,” Unsalan said, referring to COVID-19 travel restrictions. “We know where it happened by the expressions in the manuscripts, but it needs on-site confirmation.”

If they can find related meteorites in the area, the victim will be the only confirmed human in history killed by a meteorite.