Key Takeaways:

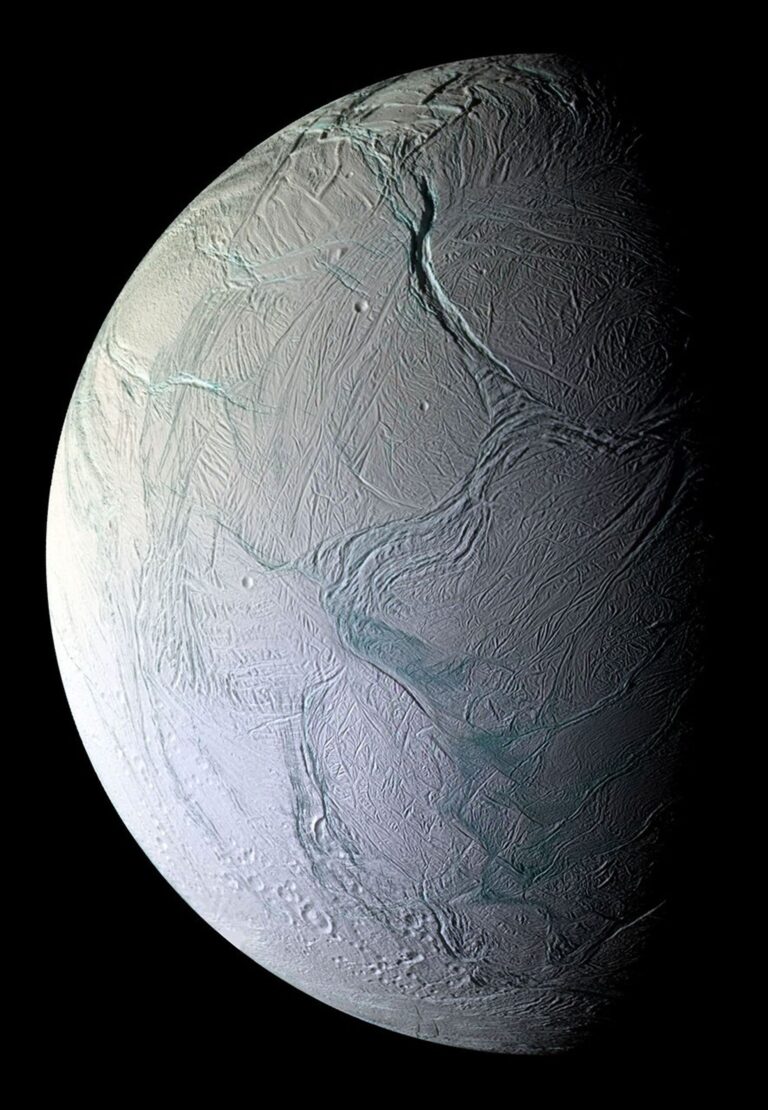

- Juno's observations reveal the existence of stable, large cyclones clustered around both Jupiter's poles, a phenomenon unseen elsewhere in the solar system.

- Analysis of Jupiter's atmosphere indicates the presence of deep, extensive winds and ammonia-rich "mushball" hailstones in mid-latitudes, challenging prior assumptions of atmospheric homogeneity.

- Juno's data suggests Jupiter possesses a diffuse core, spread across nearly half the planet's diameter, contrasting with previous models of a compact, solid core.

- The spacecraft's measurements reveal an unexpectedly complex and asymmetrical magnetic field, differing significantly between the northern and southern hemispheres and unlike any other planetary magnetic field in the solar system.

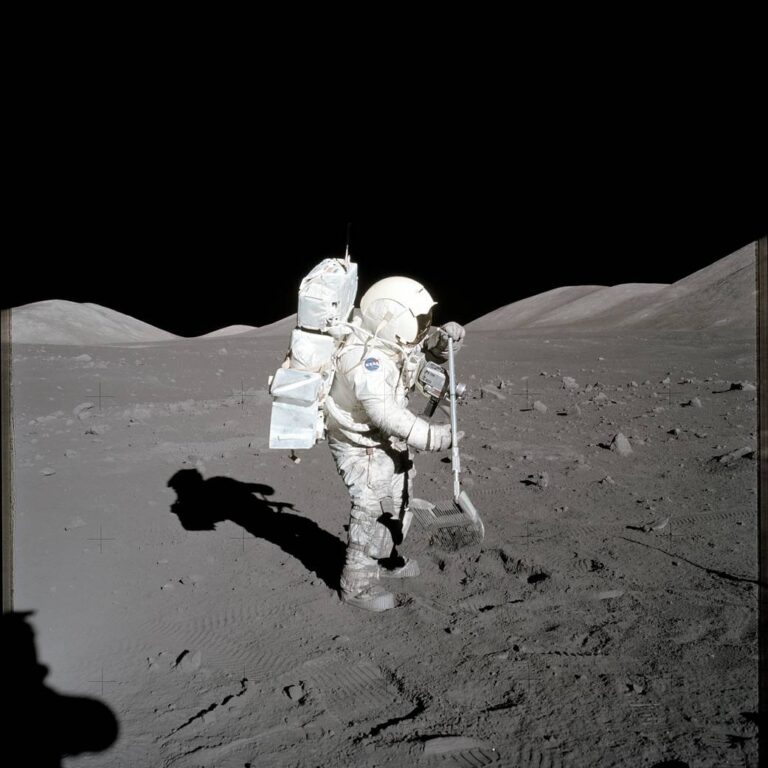

Untangle the mysteries of our solar system’s planets and moons. Check out Astronomy’s free downloadable eBook, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Planets, which contains everything you need to know about our solar systems major players.

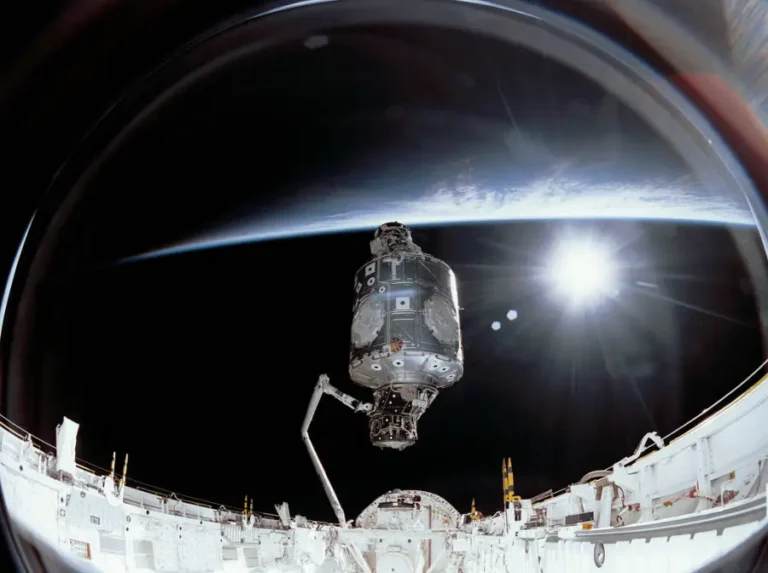

With a little over a year left in the probe’s primary mission, Juno scientists are busy trying to understand how all the intriguing disparate discoveries mesh into a coherent picture of Jupiter’s inner life. The primary mission is scheduled to last until July 2021, though the team hopes to extend Juno’s visit for a few more years beyond that.

Meanwhile, here are four of Juno’s greatest hits to date.

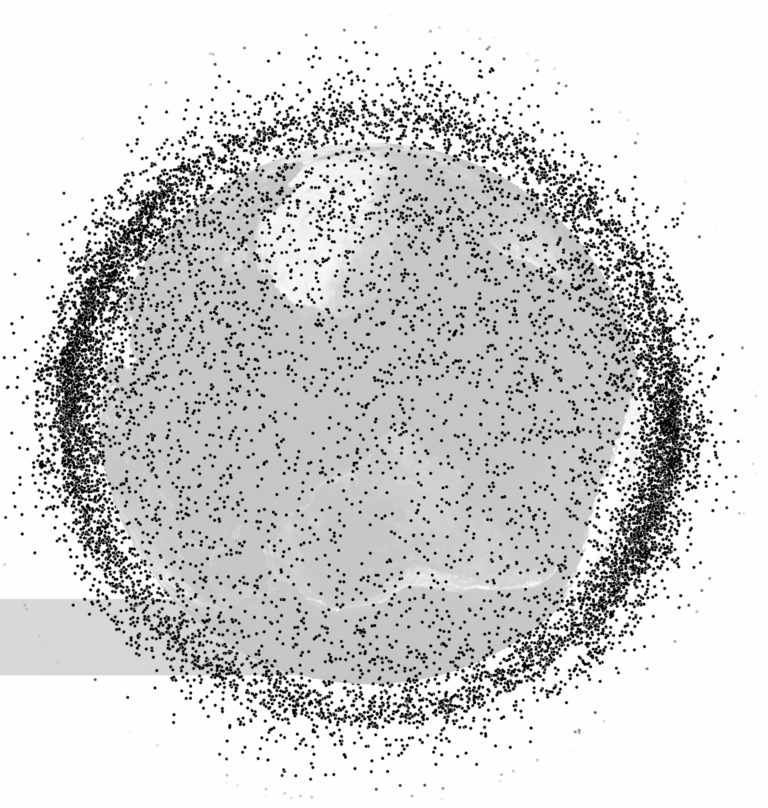

Polar cyclone party

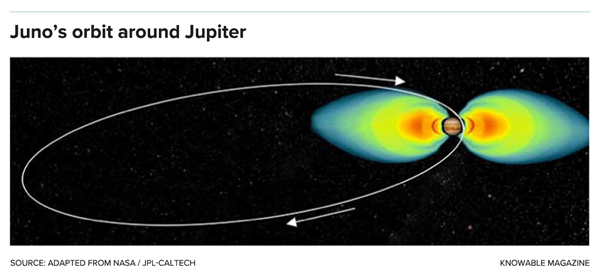

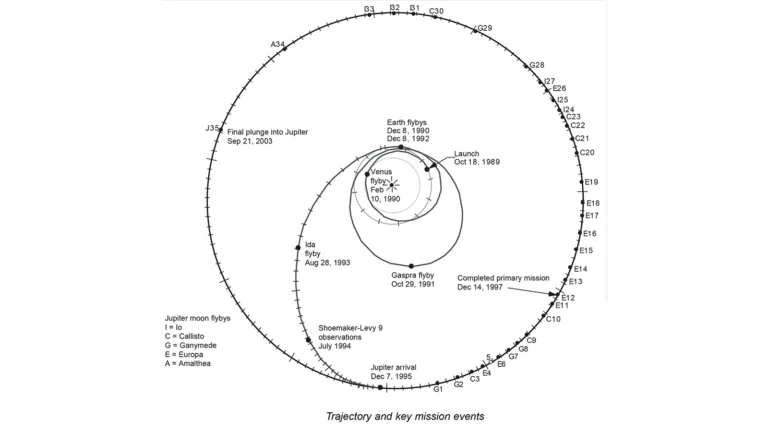

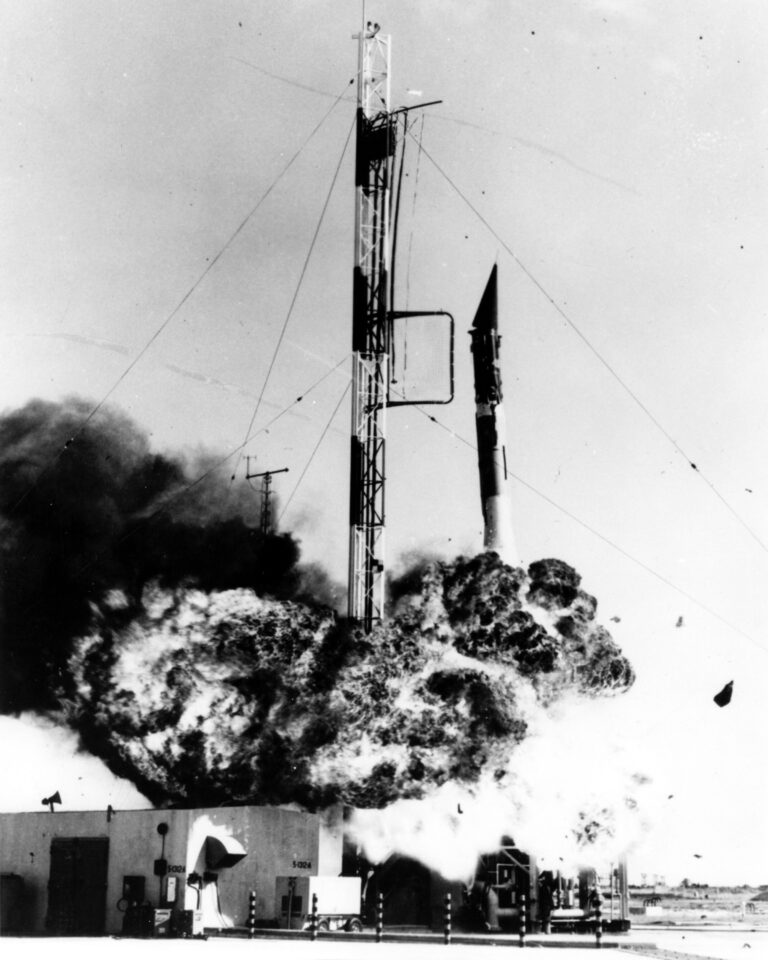

Juno is justly famous for its surreal photos of Jupiter’s swirling cloudscapes. But while the probe does have an excellent camera, not to mention a fanbase of amateur Jupiter enthusiasts ready to transform its images into science art, what makes these photos truly unique is Juno’s highly elongated, 53-day orbit: a trajectory that maximizes the spacecraft’s science potential while minimizing its exposure to Jupiter’s fierce radiation belts.

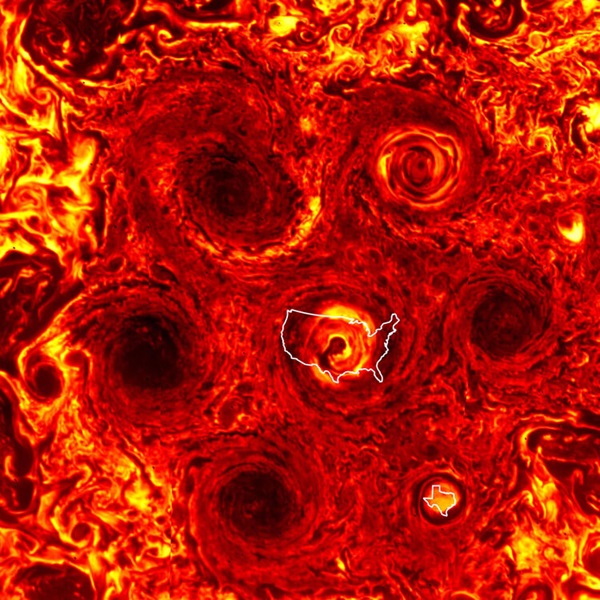

Around the planet’s south pole, Juno spied five cyclones, each wider than the United States, parked around a central cyclone of the same size. Not to be outdone, the north pole revealed eight similar cyclones encircling their own polar vortex. Remarkably, the storms didn’t seem to be going anywhere. With each of Juno’s flybys, the storms stayed put.

And then in November 2019, during Juno’s 22nd loop around the planet, it discovered that a new, smaller cyclone — merely the size of Texas — had sprung to life in the south and joined the others.

Complexity under the clouds

Because Jupiter is what astronomers call a gas giant planet, there is no point asking what conditions are like on its surface: It doesn’t have one. Instead, the hydrogen and helium gas that make up the bulk of Jupiter’s atmosphere simply get denser and denser the farther down you go, until the hydrogen becomes a liquid metal.

But there is still plenty of action in Jupiter’s swirling clouds, which are thought to be a mix of water and ammonia. And, as researchers have discovered via a microwave instrument that lets Juno probe beneath the clouds, there is plenty of complexity underneath as well.

And then there is the case of the missing ammonia. “We had assumed … that as soon as you drop below the [clouds], everything ought to be well mixed,” says mission lead Scott Bolton, a planetary scientist at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. Jupiter is, after all, a rapidly spinning ball of fluid (a day lasts just under 10 hours). But Juno’s microwave readings show that this mixing picture holds true only near the equator. It falls apart as you move north or south into Jupiter’s midlatitudes, where there is nowhere near as much ammonia as researchers expected.

To see why, Tristan Guillot, a planetary scientist at Côte d’Azur Observatory in France, and others developed computer models of Jupiter’s atmosphere and found that, away from the equator, ammonia might readily dissolve into water ice particles lofted up from below. This would reduce the amount of ammonia gas in these areas. It also means that the weather in Jupiter’s midlatitudes may feature hail-like storms of ammonia-soaked “mushballs”: frozen nuggets of roughly one part ammonia and two parts water.

A humongous smeared-out center

Although Jupiter doesn’t have a surface, researchers had a running argument before Juno’s arrival as to whether the planet had a core — a solid ball of heavier elements gathered at the planet’s center. They could argue it either way. In one common tale of Jupiter’s birth, rocky debris slowly coalesced into a solid mass up to 10 times as hefty as Earth. The gravity of that mass then hoovered up all the gas in its vicinity, surrounding itself with the deep hydrogen-helium atmosphere we see today. But in a different origin story, a pocket of gas swirling around the infant sun collapsed in on itself, creating a more-or-less pure hydrogen-helium world without a rocky core.

Juno seems to have ruled out the latter scenario, Bolton says. By tracking how the spacecraft subtly speeds up and slows down in response to variations in the planet’s gravitational field, scientists have been able to deduce how mass is distributed in Jupiter’s depths. And their maps show that Jupiter does indeed have a core — just not one that looks anything like what they expected. Instead of being a compact ball, the actual core is a fuzzy sphere spread across nearly half of Jupiter’s diameter.

Hybrid magnetism

Jupiter’s huge fuzzy core undoubtedly has implications for other aspects of the planet’s behavior — one of them being the planet’s unusual, contorted magnetic field.

For decades, the textbook picture of the Jovian magnetic field was that it resembled Earth’s — which is to say that it looked like the field of a really big bar magnet, with a well-defined magnetic north pole on one end and a well-defined south pole on the other. Quick peeks from earlier spacecraft seemed to confirm that picture.

But the textbooks were wrong. Juno’s measurements show that the magnetic field in Jupiter’s northern hemisphere looks completely different from its southern counterpart. It’s as if someone took a bar magnet, bent it almost in half, frayed one end, split the other end, and then stuck the whole thing in the planet at a cockeyed angle. In the north is the frayed end: Rather than emerging around one central spot, the magnetic field sprouts like weeds along a long high-latitude band. In the south is the split end: Some of the field plunges back into the planet around the south pole while some is concentrated in a spot just south of the equator.

This magnetic field geometry is not seen anywhere else in the solar system. The southern hemisphere resembles Earth’s field, which scientists call dipolar (because it has two poles). The north has more in common with Uranus and Neptune, where the fields are more complex.

“It was weird to have essentially … one hemisphere Earth and one hemisphere Uranus and Neptune,” says Kimberly Moore, a Caltech astrophysicist and a lead author of several studies of Juno’s magnetic findings.

Planetary magnetic fields are generated by electrically conductive fluids in their interior. The unusual fields at Uranus and Neptune may be due to these fluids being restricted to a thinner region of the planet, relative to their size. Something similar might be happening at Jupiter thanks to its dilute core, says Moore. The north-south dichotomy may also emerge from all this complexity.

“That can really change the geometry of the patterns you can come up with,” she says. But that’s just one idea. Helium rain might also wreak havoc on the magnetic field, as could penetrating winds.

Giant distinctions

If Juno has taught us nothing else, it’s that no two giant planets are alike. At first glance, Jupiter has a lot in common with Saturn, for example. But despite both being big balls of mostly hydrogen and helium, they’ve gone down quite different paths.

Jupiter has conga lines of polar cyclones; Saturn has just one vortex per pole (one of which is six-sided!). Jupiter’s magnetic field is a hodge-podge; Saturn’s is pretty boring. Jupiter’s atmosphere is multicolored and banded; Saturn’s is relatively unblemished.

“Giant planets must come in different flavors,” Bolton says. “We need to understand that if we’re going to understand them in general, because the same physics must dictate everything.”

10.1146/knowable-060420-1

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.