Rumors of a “mutiny” that took place aboard the Skylab space station in the 1970s have persisted for nearly half of a century. A cursory search turns up dozens of references to the event, with many sources claiming the astronauts went on strike, purposefully turning off their radios and refusing to talk to ground control for periods ranging from 90 minutes to a full day. During this time, the astronauts reportedly lounged around, often staring out the window at an endless black void encasing the bountiful blue marble below them.

That’s how the legend goes, at least. And it’s undoubtedly a great story. But did it really happen?

Repurposing Apollo parts for Skylab

Partly due to waning public interest, the Apollo program wound down by the early 1970s, leading to the cancellation of Apollo missions 18, 19, and 20. But scrapping these missions meant that some already manufactured equipment, including unused Apollo rockets and rockets stages, would go to waste.

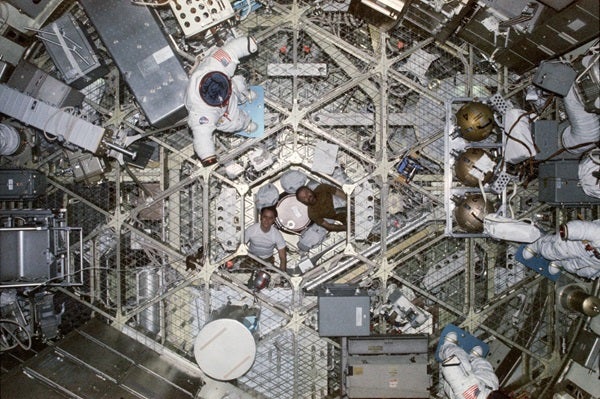

This led NASA to create the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), allowing them to make good use of some remaining Apollo hardware. Among the myriad leftover parts was a fully functional Saturn V lunar rocket, which was capable of putting 310,000 pounds of payload into low Earth orbit. The focus of the AAP became converting this roughly $750 million (adjusted for inflation) piece of equipment into the Skylab space station, which would essentially boil down to a highly modified Apollo Saturn V third stage. One of the third stage’s cavernous fuel tanks was converted into a livable space that could be occupied by three astronauts at a time.

The Skylab space station was launched unmanned on May 14, 1973, serving as the last payload ferried into space aboard a Saturn V rocket. That mission was called Skylab 1.

The next, Skylab 2, carried the first crew to the space station, where they famously spent 28 days repairing severe damage the station had suffered on its way to orbit.

As part of Skylab 3, the next crew stayed aboard the station for 59 days, carrying out scientific work and experiments. This mission, commanded by Apollo 12 moonwalker Alan Bean, along with crewmates Owen Garriot and Jack Lousma, was famously productive. So much so that the crew essentially competed all of their tasks and work with plenty of time to spare. They ended up requesting more to do before returning to Earth.

Skylab 4, the final mission aboard Skylab, was crewed by Commander Gerald Carr, Science Pilot Edward Gibson, and Pilot William Pogue. This flight — which ultimately stretched into a then-record-breaking 84 days in continuous orbit — is when the so-called “mutiny” in space took place.

Tensions mount during Skylab 4

When the Skylab 4 crew blasted off to the space station on November 16, 1973, NASA expected them to get up to speed quickly and work just as efficiently as previous crews. The space agency had plans to account for every minute of the astronauts’ 24-hour workday, including making the astronauts eat their meals while working and limiting their sleep breaks. The crews’ schedules were so regimented, if fact, that it was hard for them to even find time to go to the bathroom.

In retrospect, NASA simply had unrealistic expectations. This is especially true considering all three crewmembers of Skylab 4 were rookies. And as a cherry on top, Pogue had developed Space Adaptation Syndrome shortly after reaching orbit, significantly compromising his effectiveness at the start of the mission.

“The schedule caught up with us,” Carr recalled in Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story, which covers the dramatic tale of the space station. “We [the Skylab 4 crew] found that we had allowed ourselves to be scheduled on a daily schedule that was extremely dense. If you missed something, if you made a mistake and had to go back and do it again, or if you were slow in doing something, you’d end up racing the clock and making more mistakes, screwing up more on an experiment, and in general just digging a deeper hole for yourself.”

Eventually the Skylab 4 crew learned that their schedule, from the start, assumed nearly the same rate of productivity and efficiency the more veteran Skylab 3 crew had by the end of their mission. As you could expect, this led to some frustration from the inexperienced Skylab 4 crew.

“Finally, we began to get a little bit testy,” Carr said. An “us versus them” mentality began to set it, with ground controllers and astronauts becoming more and more aggravated with each other. As Lead Flight Director Neal Hutchinson said in the same book, “Of course as we continued to press [the astronauts], more mistakes began to be made, more than we had seen with the other crews.”

However, Hutchinson conceded “it was clearly a case of the control center not recognizing that people need some zero-G adjustment time before they can really be productive.”

In space, no one can hear you strike

Growing ever more irritated, each member of the Skylab 4 crew took turns keeping in constant contact with the ground. However, per Gibson in Homestead, one day they got their signals crossed, and the crew had zero contact with the ground for a full 90 minutes.

“When we came up to AOS (acquisition of signal) over one of the sites, the ground called us and we didn’t answer them for a whole orbit,” Gibson said. “Regrettably, that caused a lot of concern down on the ground. And of course, the press just thought that was wonderful.”

A simple mistake, it appears, is at the heart of the story of the mutiny. “There was no ‘strike in space’ by any stretch of the imagination,” Gibson said.

Following the missed communication, the crew and the ground controllers had a heart-to-heart talk spread out over several consecutive orbital passes above the United States. The crew explicitly requested more time to rest, a less densely packed schedule, and more control over when and how they did things. They also wanted to stop having exercise time scheduled right after meals, which was making them feel sick.

Ultimately, the crew was granted much more freedom in how they went about their days. And soon thereafter, their productivity began to rise.

What the Skylab 4 ruckus taught us

The Skylab 4 mutiny — or, perhaps more accurately, kerfuffle — has been widely studied by space psychologists, and a version of the story was even used as an example at Harvard Business School.

Largely because of the contentious mission, crews on the International Space Station (ISS) are now given ramp-up time instead of being forced to barrel into their work right away. NASA also instituted a policy against sending all-rookie crews to space, and both astronauts and ground controllers are encouraged to discuss potential problems and gaps in communication early on, before they snowball out of control.

The events of the Skylab 4 mission are not only relevant to astronauts aboard Earth-orbiting space stations, but also to crews that will venture back to the Moon in the coming decade, as well as those that will eventually press on to Mars. And due to the recent uptick in private spaceflight, commercial astronauts may soon jump into the fray, too.

In the end, an uncooperative astronaut doesn’t really have a choice on whether or not they work with ground controllers; their lives likely depend on these Earth-based guides.