Key Takeaways:

On July 4, 2015, there was no Independence Day celebration for Sol Alan Stern. Instead, he was hunkered down in his office talking to the New York Times. It was just three days before the project he’d shepherded, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, was set to begin a daring flyby of Pluto, which would be the first time a spacecraft visited the famous dwarf planet.

He hung up; his phone buzzed again. He stared at the caller’s name. It was Stern’s good friend, Glen Fountain, who was then the mission’s project manager. Stern knew that — unlike himself — Fountain had taken Independence Day off. This is not good, Stern thought. He picked up. In a grave voice, Fountain intoned, “Alan, we’ve lost contact with the spacecraft.”

“That’s about as bad as it gets,” Stern tells Astronomy, looking back on the episode five years later.

After receiving the stomach-sinking news, Stern hopped in his car and raced across the campus of Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, to New Horizons mission control, where team members began gathering. “People were coming in in their bathing suits and flip flops,” Stern says, who’s normally based at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “They didn’t know if we were going to be there for an hour, or overnight, or for days.”

It turned out to be days. While almost 3 billion miles (4.76 billion kilometers) from Earth, New Horizons had suffered a glitch that wiped out all of its flyby software commands — an intensely choreographed nine-day sequence of science observations that the craft would perform as it screamed by Pluto, coming within a mere 7,750 miles (12,500 kilometers) of the dwarf planet.

New Horizons’ glitch in 2015 set off a nonstop 76-hour scramble to upload and rebuild all the necessary flyby software. That meant not only recreating the full set of commands, but also the ephemeris files and other software libraries on which they depended. Such a task would normally take weeks, Stern says. He likens it to a chess match with a nine-hour time delay, which is how long it took for radio signals to make a round trip to the New Horizons spacecraft.

The result? Stern and his team restored the software with just four hours to spare before the flyby sequence began.

That Herculean effort saved New Horizons from being a “laughingstock,” says Stern. The mission ultimately returned a treasure trove of data that scientists are still analyzing today, resulting in well over 100 peer-reviewed papers. And for the scientists and engineers who built it, watching Pluto grow ever larger as New Horizons approached was the scientific experience of a lifetime.

“Every day, it was a matter of being astounded,” Cathy Olkin, a planetary scientist at SwRI, tells Astronomy.

Plotting the course for New Horizons

New Horizons’ nine-day flyby sequence culminated with its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, when it followed a trajectory carefully plotted by Yanping Guo, a mission design specialist at APL. Guo has also worked on the Parker Solar Probe, NASA’s Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) mission in the 1990s, and seven other mission studies or proposals. She began charting a course for New Horizons way back during its design phase in 1999 — some seven years before its launch.

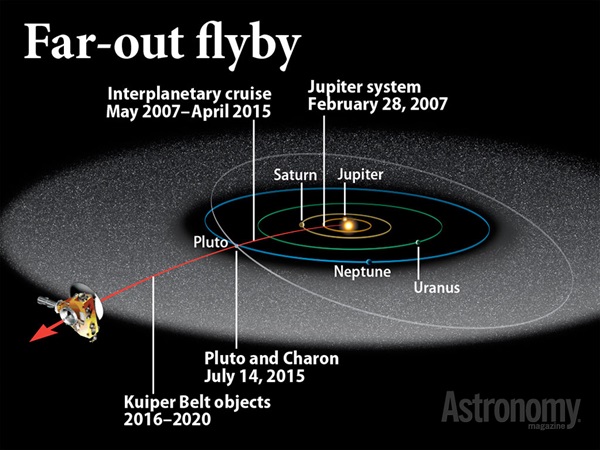

The New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto and Charon in July 2015, before continuing on to visit the Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth. Though originally planned to explore the Kuiper Belt until 2020 (as seen in this graphic), Stern says that New Horizons mission has been extended until 2025.

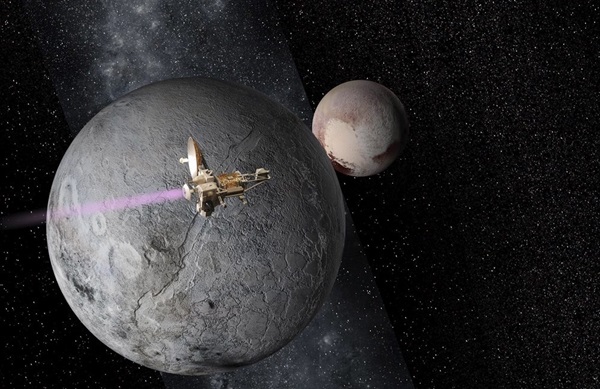

Her calculated trajectory took advantage of a speed-boosting slingshot maneuver around Jupiter. But the most crucial celestial alignment was during the flyby itself. Mission scientists wanted to take solar occultation measurements to study the atmosphere of Pluto. This meant having the spacecraft look at the Sun just as it slipped behind Pluto, where it would then measure how the world’s thin blanket of air affected the solar radio waves passing through it. In addition, scientists also wanted to repeat the measurement when Pluto occulted Earth, this time beaming the radio signals from NASA’s Deep Space Network of communication facilities. Finally, they wanted to repeat both experiments for Pluto’s moon Charon.

Keep in mind, these ambitious goals were on top of the high-resolution images and observations New Horizons already planned to take when it reached its closest approach to both Pluto and Charon.

“It’s the most comprehensive observations you could want for any flyby mission,” says Guo. “It was hugely rewarding, personally, for me.” Guo’s planned trajectory was truly a marvel of metronomic precision.

Are you ready to see what New Horizons learned at Pluto? Check out our free downloadable eBook, The strange, icy world of Pluto to learn more about the groundbreaking mission to this distant world.

Pluto: A geologically active world

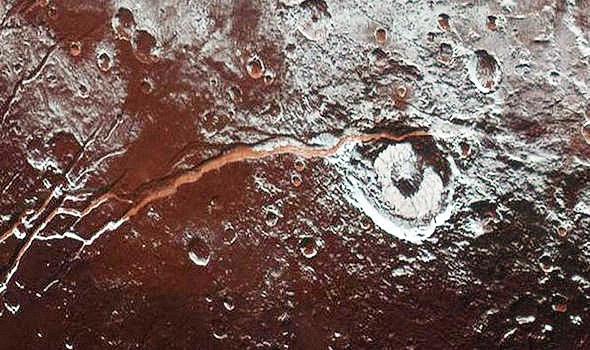

The scientific payoff of New Horizons was nothing short of spectacular. From the very first images, the spacecraft stunned researchers with the sheer variety of geological features it revealed — from mountain ranges that rival the Rockies, to expansive and active glaciers, to a shimmering blue atmosphere of nitrogen with multiple layers of haze.

“I was frankly astounded,” says Olkin, who worked on an imager and spectrometer called Ralph, one of New Horizons’ primary instruments. Before the flyby, she and her colleagues had debated whether mountains on Pluto were even possible. “We knew that there were nitrogen, methane, and carbon-monoxide ices on the surface,” she says, but they “would tend to be kind of soft.” So when New Horizons’ captured mountains climbing as high as 11,000 feet (3500 meters) above Pluto’s surface, the researchers knew the features had to be made mostly of water ice. That was the only type of ice on Pluto strong enough to act as a bedrock for their hulking, mountainous forms.

Even more surprising were the glaciers, like those found on the surface of Pluto’s icy heart — its most famous surface feature, which was revealed in the first high-resolution image from New Horizons. The science team had an informal betting pool running, with a bingo-type chart of geologic features, says Stern. Most put a dollar down on a couple predicted finds. And as the data came in, the team quickly checked off virtually every square. But glaciers weren’t even on the board. “We didn’t have any glaciologists on our team,” says Stern.

Perhaps most profoundly, over the past five years of analysis, researchers have found a growing body of evidence that Pluto has a liquid water ocean beneath its icy surface shell. And if underground oceans are possible on Pluto, that could greatly expand the range of planetary bodies in the outer solar system where life is possible.

Put together, New Horizons’ data paints a picture of a dynamic body alive with geological activity, boasting more internal energy and heat than scientists had ever dreamed of. “We now have a more nuanced and complex view of our solar system, which really translates to how we view other solar systems,” says Olkin.

That includes the search for alien life, as well. “You can forget the old concept of a ‘habitable zone’,” says Stern, referring to the narrow zone around stars where planets can host liquid water on their surfaces. “It just doesn’t matter to things in the Kuiper Belt. The outside [of Pluto] is inhospitable to biology as we know it, but the inside is warm and cozy, and protected from supernovae and giant impacts.”

A new orbiter mission to Pluto?

Stern is now advocating for another mission to Pluto. But this time, the craft would enter into orbit around Pluto, using gravity assists from Charon to navigate throughout the entire plutonian system. The proposed Pluto orbiter would be similar to NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn, which made a thirteen-year “Grand Tour” of the ringed planet and its moons from 2004 to 2017.

The fate of the Pluto orbiter, however, will likely be determined by the results of the planetary science community’s decadal survey, which are due in 2022. This broad-reaching and thoroughly debated survey is when the entire astronomical community comes together to determine its future research and exploration priorities, which are eventually presented to policymakers.

“[A Pluto orbiter] doesn’t require inventing new technologies,” says Stern. “But it requires a lot of patience because it’s a longer mission compared to New Horizons.” That’s because while New Horizons simply whipped by the dwarf planet before continuing on to the Kuiper Belt, an orbiter has to go slow enough that it can be captured by Pluto’s meager gravity.

But a Pluto orbiter is just one of many flagship-class mission concepts NASA is considering. Other proposals include sending an orbiter, rotorcraft, or even submersibles to Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, with the latter capable of exploring the moon’s mysterious methane seas.

“[Pluto orbiter] is in the playoffs, if you will,” as Stern puts it. “But that doesn’t mean it’s gonna win the Super Bowl.”