Since 2016, some scientists have suspected that a massive, unseen world may be lurking in the outer solar system — a world called Planet Nine. The evidence comes from the strange orbits of some smaller objects past Neptune that all seem to be influenced by a bulky, hidden planet far beyond Pluto. But then, just last year, scientists thought of another explanation, and it’s straight out of sci-fi. The researchers proposed that the so-called Planet Nine isn’t a planet at all. Instead, they suggest that the solar system could be home to one of the universe’s earliest black holes: a primordial black hole.

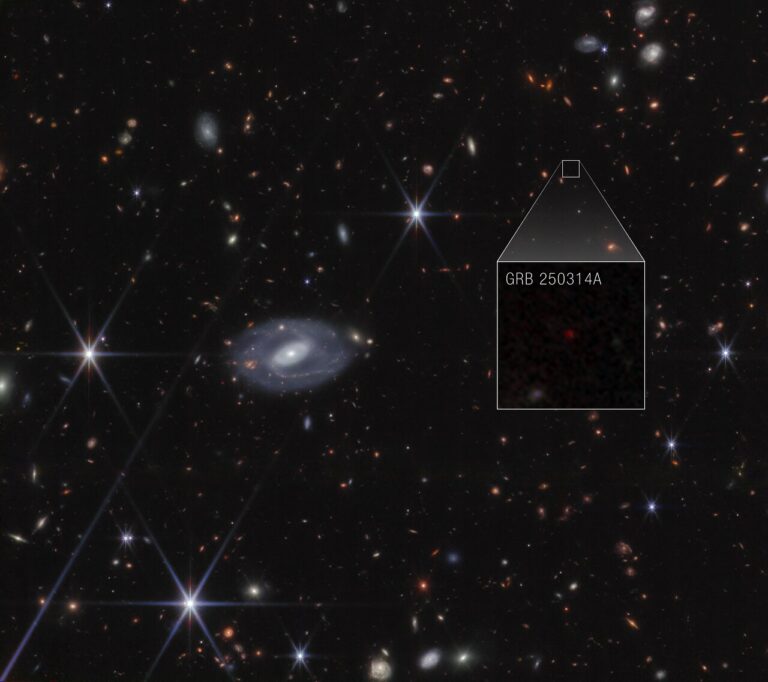

Now, Harvard scientists have proposed a way to determine, once and for all, whether Planet Nine actually could be a black hole. Specifically, the new method would scour the outer solar system for evidence of telltale flares that are emitted when a black hole devours a comet or other distant object. Such flares, they say, should be detectable by the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which is expected to begin a 10-year survey of the southern sky within the next few years.

What is Planet Nine?

The Sun’s influence stretches far beyond what most people typically think of when it comes to the solar system. For example, it took 36 years and about 12 billion miles (19 billion kilometers) for the first human-made object, Voyager 1, to leave our Sun’s protective bubble, called the heliosphere. Therefore, it isn’t surprising to learn that scientists are still finding new icy objects orbiting well beyond Neptune, known as Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). At the end of 2018, for instance, researchers announced the discovery of the then-most distant TNO known, nicknaming it FarOut. Just a few months later in 2019, the same team trumpeted their discovery of an even more distant TNO, calling it FarFarOut.

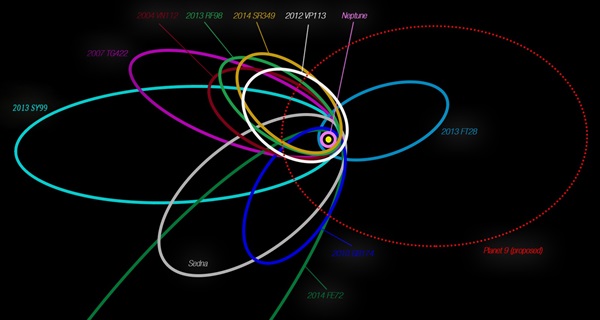

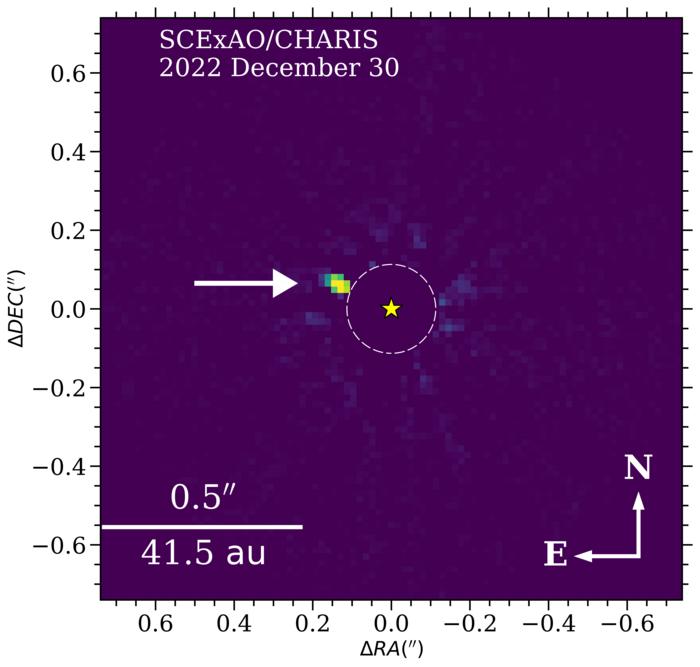

But unlike FarFarOut, FarOut’s orbit — along with a handful of other extremely distant TNOs — is quite strange. Research shows that about a dozen distant TNOs make their closest approach to the Sun, or reach perihelion, at nearly the exact same point in space. But they can’t explain why. These objects are located roughly 100 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU equals the average Earth-Sun distance) from the Sun, which puts them far beyond Neptune’s gravitational influence. This puzzle is what led researchers to calculate how a hidden planet — a world some five to 10 times the mass of Earth and located anywhere from 400 and 1,500 AU from the Sun — may be shepherding these unique TNOs into position.

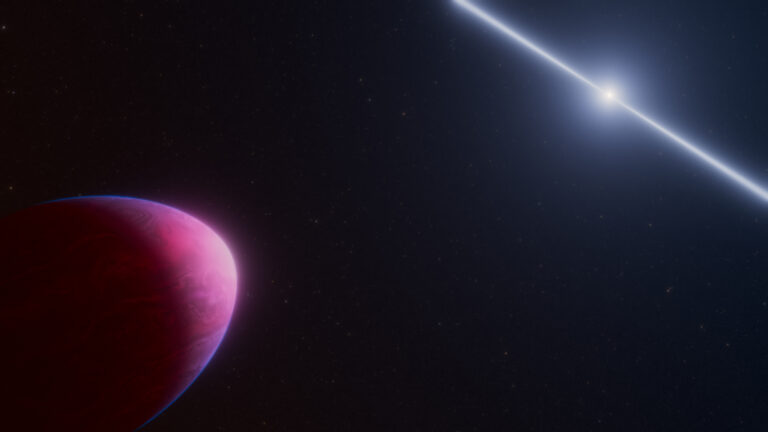

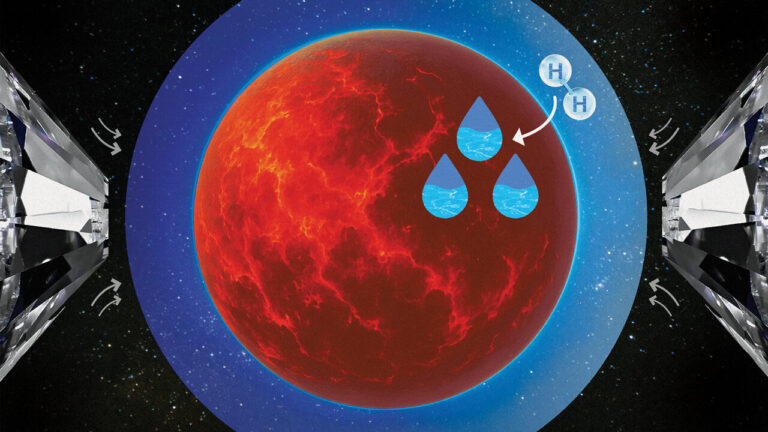

On the other hand, Planet Nine might not be a planet at all. It could be a primordial black hole — and with Planet Nine’s suspected super-Earth status, that black hole would only be roughly the size of a grapefruit. Theory says that such tiny black holes could have popped into existence within the first few fractions of a second after the Big Bang (making primordial black holes a possible candidate for dark matter). But the existence of these ancient beasts has yet to be confirmed.

Vera Rubin (Observatory) aims to deliver the final verdict

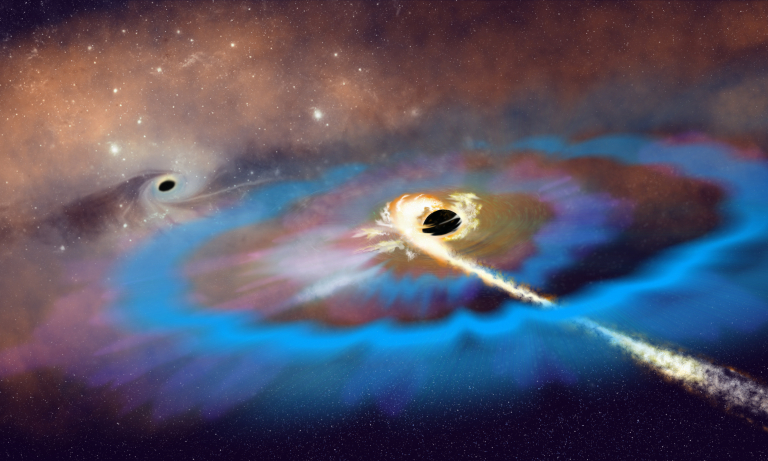

Normally, black holes are extremely difficult to locate. As their name suggests, nothing, including light, can escape their gravitational grasp once it gets too close. Instead, scientists must pinpoint black holes by observing their influence on nearby objects, or, alternatively, by catching bright flares of light that are emitted when matter spirals into them.

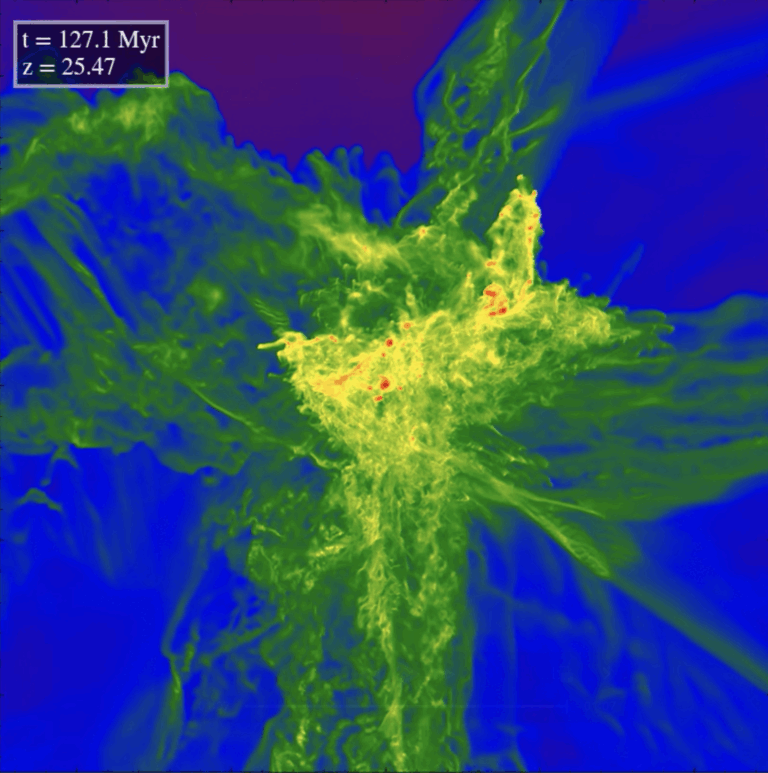

So, to search for black holes in the distant solar system, astrophysicist Avi Loeb of Harvard, along with Harvard undergraduate Amir Siraj, developed a method to seek out flares generated when a black hole encounters small objects in the Oort Cloud, which is a vast shell of potentially trillions of icy bodies that cocoons our solar system. Occasionally, the researchers say, Oort Cloud objects like comets should interact with any black holes lurking around, producing a visible flare of light that the Vera C. Rubin Observatory could detect when it starts its 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

This isn’t an entirely new idea, however. Delivering a final verdict on whether a ninth planet is hiding in our solar neighborhood was already one of the goals for LSST. But in terms of spotting a planet-mass black hole, the groundbreaking survey happens to be perfectly suited for the job.

“Neither of us expected it to conveniently fall within the range that LSST is going to look at,” Siraj tells Astronomy. “But also, beyond just a Planet Nine black hole … we can rule out or confirm [any] planet-mass black holes all the way to the edge of the Oort Cloud.”

If LSST does end up spotting a flare from a primordial black hole masquerading as Planet Nine, another telescope of similar sensitivity could then focus on its location for much longer, likely capturing thousands more flares. But Siraj says that even if the survey doesn’t detect any flares, “we can place very tight limits on the fraction of dark matter that’s tied up in primordial black holes.”

All things considered, Loeb and Siraj expect LSST to have definitive proof of whether or not a planet-mass black hole is lurking in the outer reaches of our solar system within the first year or two of the survey. But even with slim chances of success, the researchers can’t help but hold their breath.

“It’s such a small probability, but to have a black hole within reach would be — I think exciting is an understatement,” said Siraj. “It would really open up a new field if we had a black hole in our backyard.”