Key Takeaways:

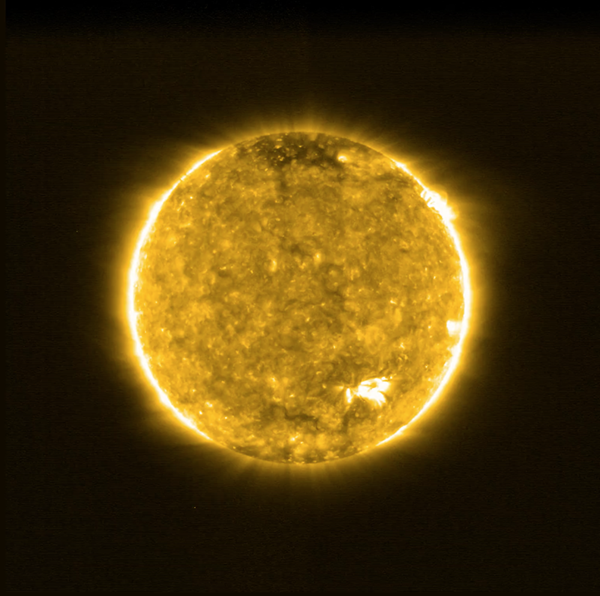

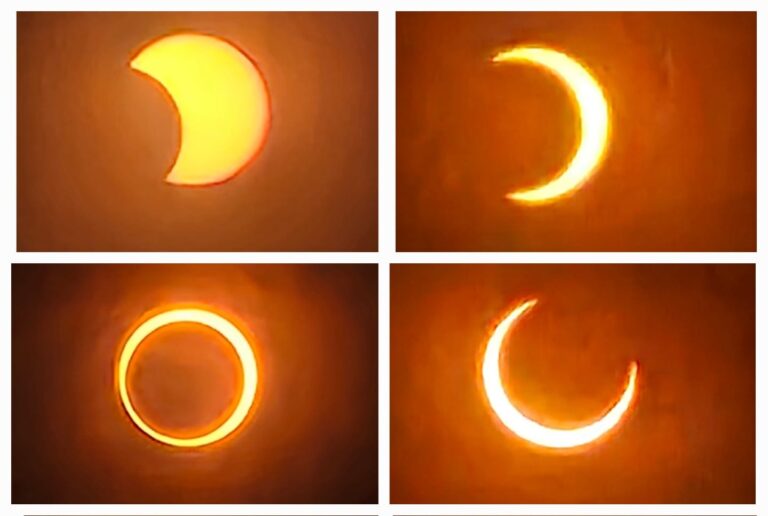

Launched February 9 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, Solar Orbiter will explore the forces that power the steam of particles constantly flowing from our Sun, called the solar wind. It will take about two years for the satellite to reach its final orbit. But once in place, its unique path will allow it to capture the very first high-resolution images of the Sun’s poles. It completed its first close pass of the Sun last month, coming within just 48 million miles (77 million kilometers) of our star. During this pass, the spacecraft’s suite of 10 instruments went to work observing our star and its surroundings.

Researchers wanted this data to simply confirm the instruments are working properly — which they are. But scientists didn’t expect to make new discoveries.

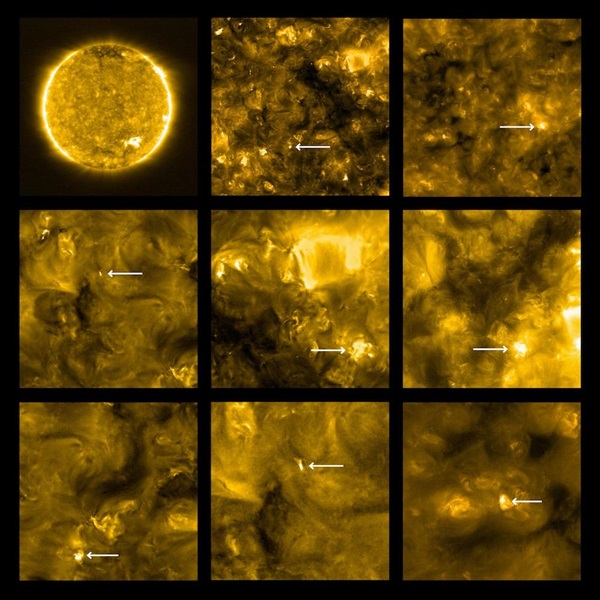

Little fires all across the Sun

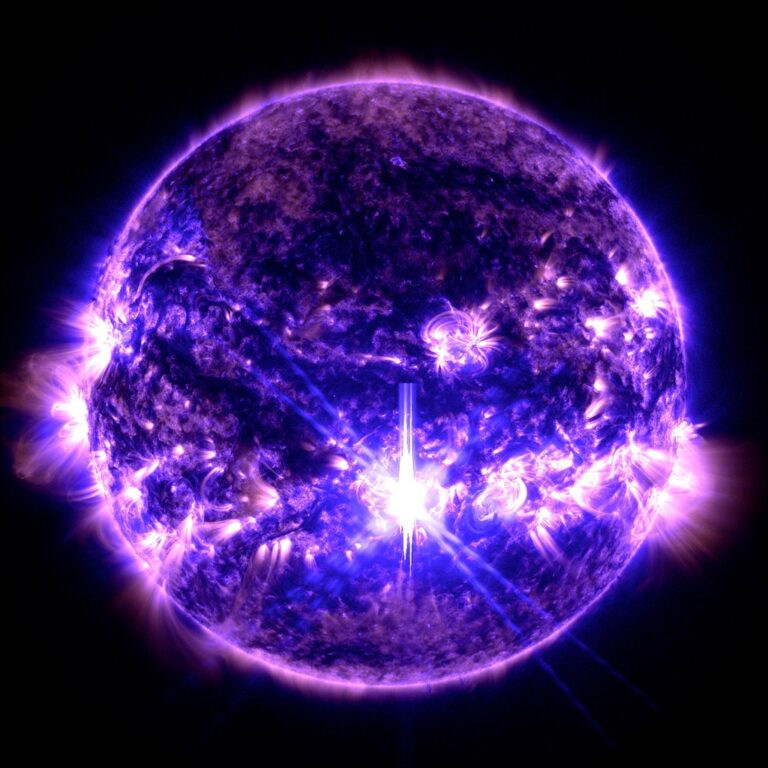

Of Solar Orbiter’s six imagers, its Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) sent back the most intriguing photos, capturing a vast army of small bright spots, each about a millionth to a billionth the size of a traditional solar flare. These so-called campfires are “the little nephews of solar flares,” said EUI Principal Investigator David Berghmans, of the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, in a press release. And they are, according to Berghmans, “literally everywhere we look.”

It’s possible these campfires are simply miniature versions of the flares we spot from Earth. But they also may be related to nanoflares, which are small, brief, ubiquitous bursts of energy that occur across the Sun and are increasingly thought to be responsible for our star’s surprisingly hot outer atmosphere, or corona. Just how the corona gets so hot — some 300 times hotter than the Sun’s surface — isn’t well understood. So, helping to solve this mystery is one of Solar Orbiter’s many mission goals. The next step, according to the Solar Orbiter team, is to eventually measure the campfires’ temperatures with the craft’s Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment instrument.

Shining dust and solar magnetism

Another instrument, the Solar and Heliospheric Imager (SoloHI), sent back shots of the zodiacal light, which occurs when sunlight reflects off dust particles in our solar system. Although these images don’t signify a new discovery, taking them required SoloHI to tamp down the Sun’s glare to just a trillionth its actual brightness. By successfully completing the task, researchers are confident SoloHI can produce the image quality needed to study the solar wind (the instrument’s intended purpose) once the mission ramps up.

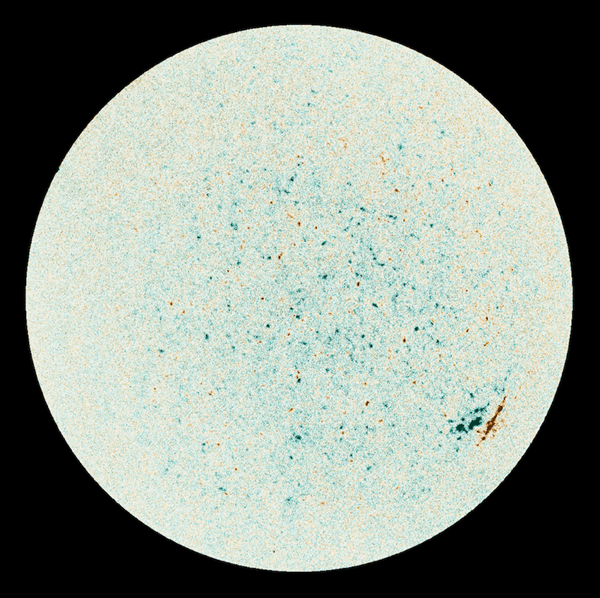

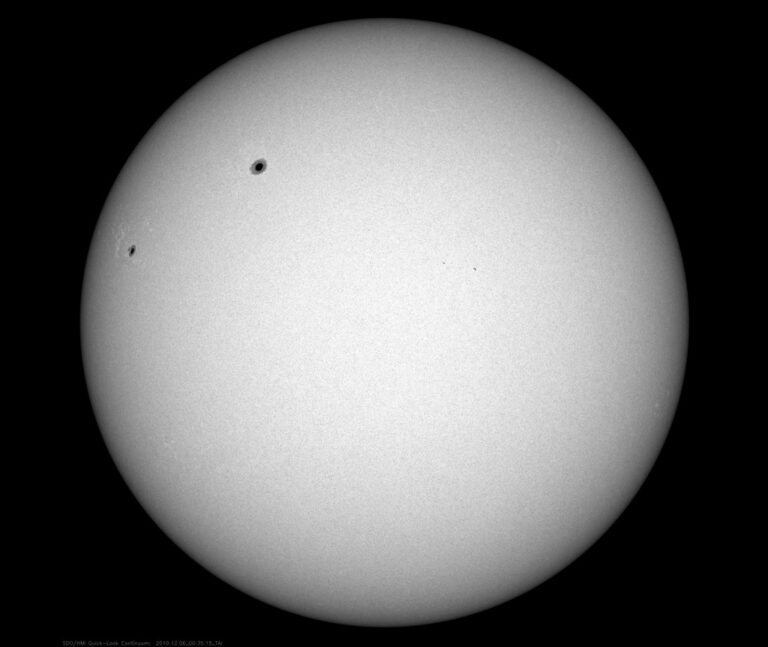

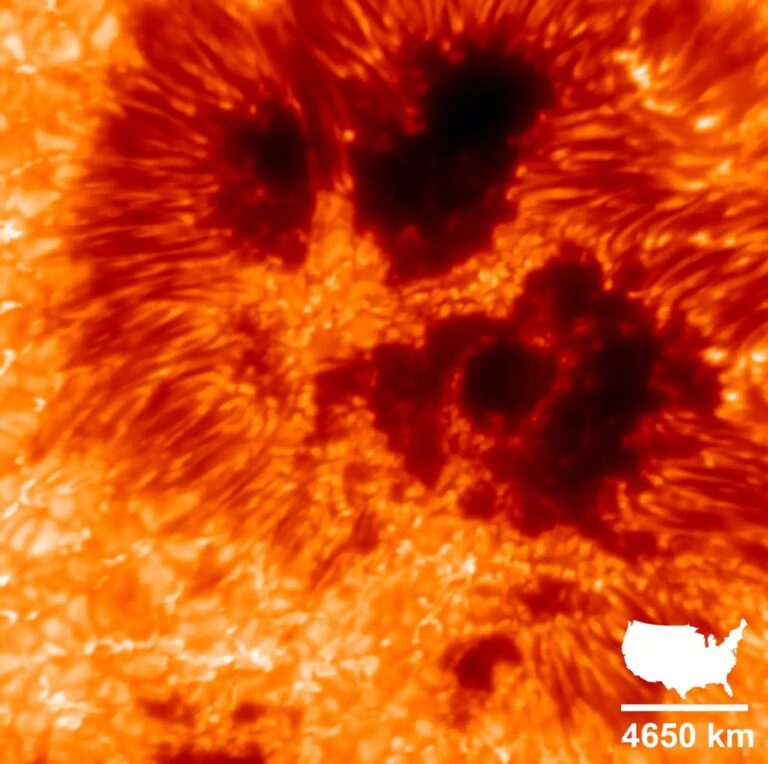

The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) also beamed back high-resolution data showing the Sun’s intricate and powerful magnetic field. And in a first, PHI revealed a view of a local magnetic field on the Sun that was not visible from Earth at the time, exemplifying just one advantage of the spacecraft’s intentionally tilted orbit.

The Sun’s magnetic field drives numerous internal processes, which can produce solar flares and other powerful outbursts. Such energetic solar events can affect us here on Earth, too — from sparking stunning auroras to knocking out satellite communications and earthbound power grids. But by monitoring the Sun with spacecraft such as Solar Orbiter and the Parker Solar Probe, scientists should be able to better predict when Earth-affecting space weather will occur.

All in all, these first results show that we still have much to learn about our home star, as well as the forces that power its frequently finicky behavior. “Solar Orbiter is off to an excellent start,” said project scientist Daniel Müller. “We are all really excited about these first images — but this is just the beginning.”