Key Takeaways:

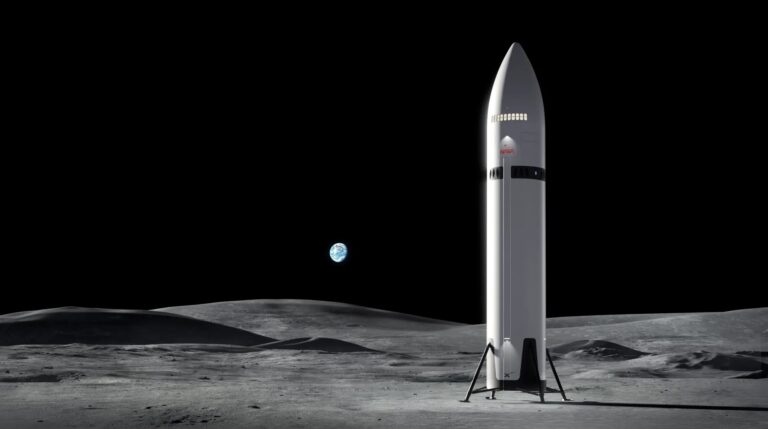

Given the state of the world right now, it’s no great surprise that President Trump’s goal to send humans back to the Moon by 2024 is in jeopardy. Many space policy experts questioned the feasibility of that deadline even when it was originally announced in March of last year. Now that we’re in middle of a global pandemic, with the U.S. economy in freefall, a 2024 lunar landing looks not just hugely ambitious, it also wildly out of touch with the immediate needs to protect public health and welfare.

And yet, the scramble to contain COVID-19 and the efforts to go back to the Moon are not really at odds with each other. Government officials regularly draw on the managerial structure and focused urgency of the 1960s Apollo program in defining the current effort to develop a coronavirus vaccine. That effort is frequently described as a “moonshot”; even its semi-official name, Operation Warp Speed, directly evokes the space age.

Conversely, there is a deep connection between the botched U.S. response to COVID-19 and the half-century absence of astronauts on the Moon. They are both case studies in the difference between potentiality and actuality — between what we can do, and what we choose to do.

If we can belatedly pull together an effective, coordinated national strategy against the virus, that would bode well for all kinds of other ambitious future undertakings, from expanding green energy and upgrading the electric grid to, yes, taking another ambitious leap in human spaceflight. And if NASA can execute an inspiring, well-run Artemis lunar program, that would be a powerful symbol of what the federal government can achieve when people work together in lock-step toward a single, meaningful goal.

Money is generally not the primary obstacle to doing great things. Compared to the trillions of dollars of economic damage unleashed by the lack of a coherent pandemic strategy in the U.S., and the trillions more in government spending required to compensate for that damage, the cost of the Artemis program is practically a rounding error.

That’s not to say that 35 billion dollars is nothing. It’s important to look critically at any project this big to be sure it is a worthy undertaking, being carried out in an intelligent and efficient way. The point is, if we want to resume human exploration of the Moon, money is not the obstacle to doing it. If we want to double the size of NASA’s Discovery program so that the agency could approve missions to Venus, Io and Triton this year, money is not the obstacle to doing that, either. Adding another Discovery mission would have an incremental cost of about 450 million dollars, or about 0.1 percent of the amount the federal government put into its secretive business bailout COVID-19 fund (I’m not even dealing here with the horrific human toll of the pandemic, which lies entirely beyond these number-driven discussions of costs and benefits).

The gap — no, make that the chasm — between what we can do and what we are choosing to do right now got me thinking about another aspect of NASA history and the Apollo program: not how it began, but how it ended. I started thinking in particular about Apollo 18, the marvelous Moon expedition that never happened.

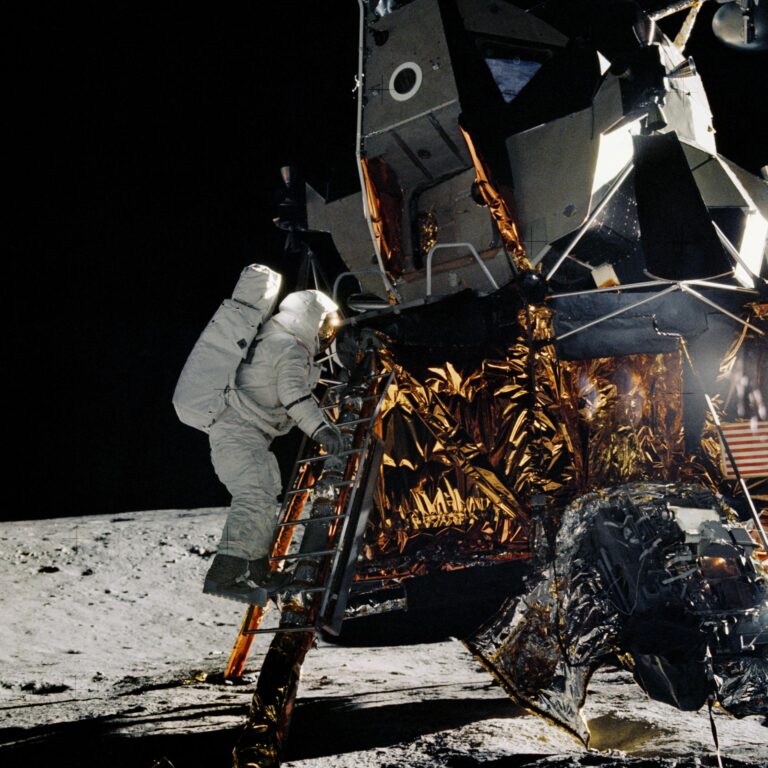

NASA had plans for three more lunar landings after Apollo 17. Most of the equipment for them was built. Two of the Saturn V rockets that would have taken them to the Moon were built. The crews had been tentatively selected. But those missions never happened, of course. In January 1970, responding to budget cuts, NASA cancelled Apollo 20. In September 1970, Congress cut off funding for Apollo 18 and 19 as well. When Apollo 17 returned to Earth on December 19, 1972, the era of humans on the Moon came to an end.

The proximate cause for the cancellation of the last three Apollo missions was that Congress was unwilling to support a continued human presence on the Moon, and President Nixon had no interest in fighting for it. Beyond the literal cost, the Apollo program seemed an extravagant waste at a time when the economy was hurting and the U.S. was still deeply enmeshed in the war in Vietnam.

It’s worth noting that the immediate budgetary impact from scrapping Apollo 18 and 19 was negligible. By NASA’s official accounting, the cancellations saved just 42 million dollars, since all of the equipment and personnel were already in place for those missions. The obstacle wasn’t money, then, and it certainly was not technology. It was a matter of will.

We easily could have gone back to the Moon one or two more times after Apollo 17. The late missions would have been the most science-focused ones. Apollo 18 was tentatively set to land in a giant impact crater, either Tycho or Gassendi. But we — the president, Congress and the public that elected them — chose not to go back.

The same is true today. If the public were clamoring for a human presence on the moon, and if the president and Congress were responsive to that demand, there would be absolutely no difficulty in carrying out NASA’s Artemis project. Or getting to work on a scientific base on the moon. Or laying the groundwork for a crewed mission to Mars.

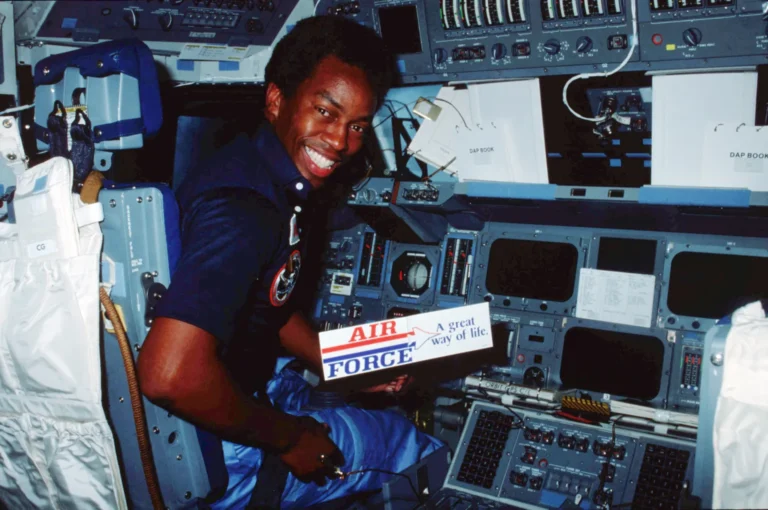

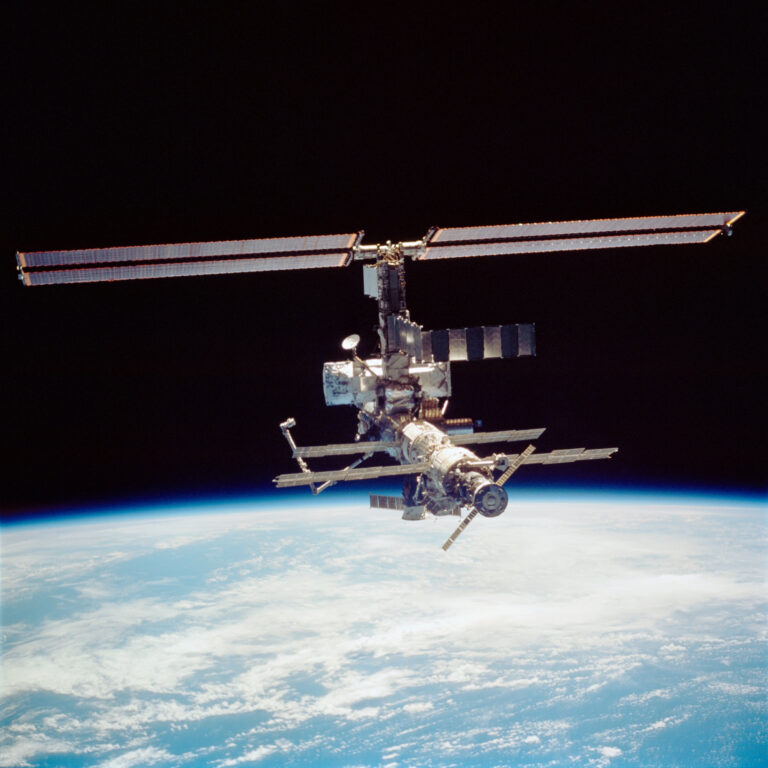

At some point over the past 40 years, every president has endorsed one or more of those goals. Then, the plans recede into the background. Nobody manages to sell the public on the idea. The president’s attention wanders. Congress’s spending priorities land elsewhere. NASA receives ever-shifting directives. The agency continues to support a wide range of valuable science and engineering projects, but the high-profile, big-ticket human spaceflight program remains locked in low-Earth orbit, where it has been since the 1970s.

Fortunately, there is a way out. If we can choose not to do things, we can also choose to do them. The COVID-19 pandemic is a gruesome demonstration of the price we pay when our elected leaders throw away the power of collective action for the greater good. But we, collectively, can decide on a different course.

A focused national vaccine program, a revitalized CDC, and a beefed-up international infectious disease surveillance network could begin a major turnaround in the ways that the federal government watches out for the welfare of the public, in the U.S. and around the world. A metaphorical pandemic moonshot could go hand in hand with a literal, rocketry-based moonshot.

Our current period of isolation could also be a moment for pursuing new high-frontier dreams in space, right alongside practical needs on Earth: upgrading our schools, healthcare system, and energy supply. The old rhetorical quip — “Why are we putting people on the moon instead of solving problems here on Earth?” — always struck me as absurd. Advances in science and engineering benefit everyone, and honing expertise in planning and executing huge projects is exactly what we need to solve problems here on Earth.

It’s hard to find a silver lining in the COVID-19 pandemic. But if it leads to an awakening to the tremendous things we can do — if only we choose to do them — that would be precious indeed.