Key Takeaways:

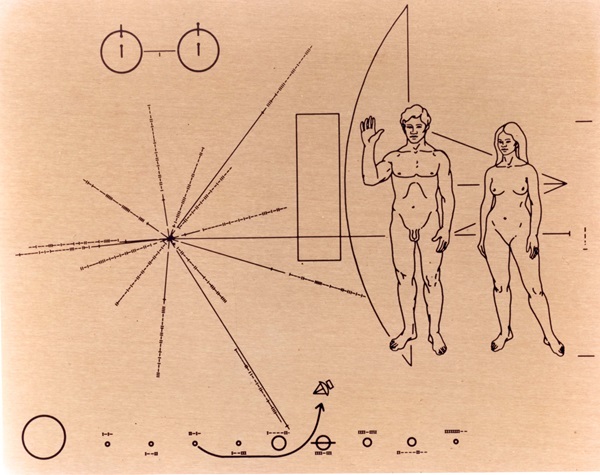

Each of these craft was primarily designed to explore worlds in the outer solar system. But when they finished their jobs, their momentum continued to carry them farther from the Sun. Astronomers knew their ultimate fate was to live among the distant stars. And that’s why all but one of these spacecraft carries a message for any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find it along the way.

Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11

In 1972, NASA hadn’t even finished sending Apollo astronauts to the Moon yet when it started launching the first missions that would ultimately wind up in interstellar space. That wasn’t the end goal though. Pioneer 10 and 11 were primarily intended to do humanity’s first major reconnaisance of other planets in our solar system.

Pioneer 10 achieved the first flyby of Mars, the first trip through the asteroid belt, and the first flyby of Jupiter. And the secret to its success was nuclear power. No NASA spacecraft had ever launched with a nuclear-powered electrical source before. So, after Pioneer 10 passed Jupiter in 1973, it still had ample power to keep going. In fact, the mission continued to communicate with Earth for a total of 30 years, rather than the 21 months NASA initially planned for.

Pioneer 11 saw similar success. It made a flyby of Jupiter in 1974 before becoming the first mission to ever encounter Saturn in 1979. Pioneer 11 revealed what the ringed planet is made of, as well as identified new moons and a new ring around the gas giant.

The identical Pioneer plaques show a nude man and woman along with an orbital diagram of our solar system. NASA no longer gets signals from the Pioneer spacecraft, but if extraterrestrial life ever finds them, they should be able to deduce what our species looks like and where we’re from

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2

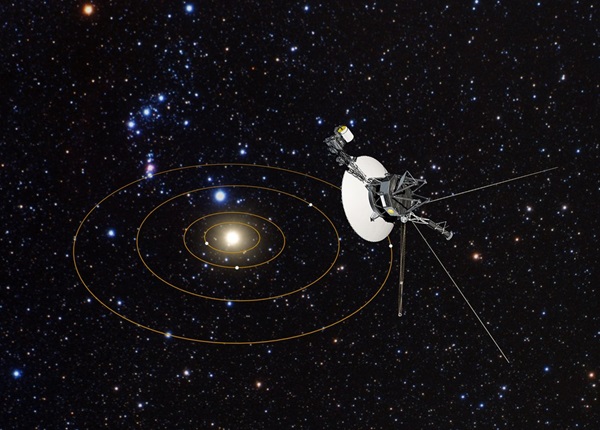

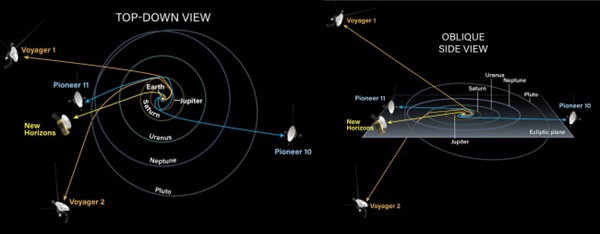

Half a century ago, NASA built its two identical Voyager spacecraft to capitalize on a rare alignment of the outermost planets that only happens once every 175 years. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune were perfectly placed, allowing scientists to chart a course that would send the spacecraft by each of these gas giants. That path also meant that, after they’d completed their tour of our solar system, both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 would continue into interstellar space.

Voyager 1 launched in 1977, made its flyby of Jupiter in 1979, and passed by Saturn in 1980. But rather than continuing on to Neptune and Uranus, like Voyager 2 did, NASA decided to send Voyager 1 on a detour past Saturn’s moon Titan — the only other known world in the solar system with an atmosphere thick enough to host a rain cycle.

That choice made Voyager 1 veer off its grand tour of the outer planets and head up and away from the orbital plane of our solar system, putting in on course for interstellar space.

Meanwhile, Voyager 2, was sent on an even bolder mission to explore the outer planets. Voyager 2 continued on past Saturn and encountered Neptune and Uranus. It still remains the only spacecraft to see those two planets up close.

That milestone was really just their first step on a long journey into the stars.

The spacecraft may be zipping along at a breathtaking 35,000 mph, but they still will take many millennia to truly leave the solar system. Voyager 1’s course could take it close to another star in some 40,000 years, while Voyager 2 won’t get close to another star for some 300,000 years, according to NASA.

However, NASA has prepared for the possibility that someone (or something) stumbles upon them along the way. Both spacecraft contain copies of the Golden Record. And as Carl Sagan noted: “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space.”

We’ll just have to hope record players are popular in other star systems.

New Horizons

Scientists fought for decades to get a mission to Pluto approved. But months after New Horizons finally launched, Pluto was demoted from planet to dwarf planet. That didn’t make the spacecraft’s findings any less incredible, though.

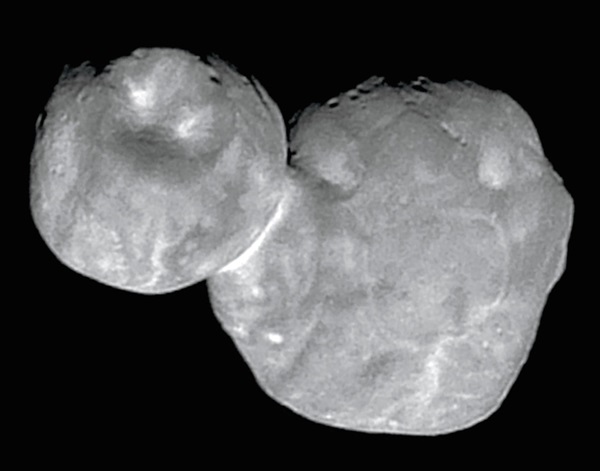

At Pluto, New Horizons found signs of ice volcanoes, giant mountains, and even a liquid water ocean. Then, the probe pushed on into the depths of the Kuiper Belt, where it explored 486958 Arrokoth, a primordial world of ice and rock that looks like two pancakes stuck together.

Now, New Horizons is continuing on in the footsteps of the Pioneer and Voyager missions, as it’s only the fifth spacecraft ever launched on a path that will take it out of the solar system.

But unlike its interstellar spacecraft kin, New Horizons doesn’t carry a plaque or a golden record designed to teach aliens about the human race. And that was intentional.

“After we got into the project in 2002, it was suggested we add a plaque,” Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator, said in an interview with CollectSPACE.com back in 2008. “I rejected that simply as a matter of focus,” he added. “We had a small team on a tight budget and I knew it would be a big distraction.”