Key Takeaways:

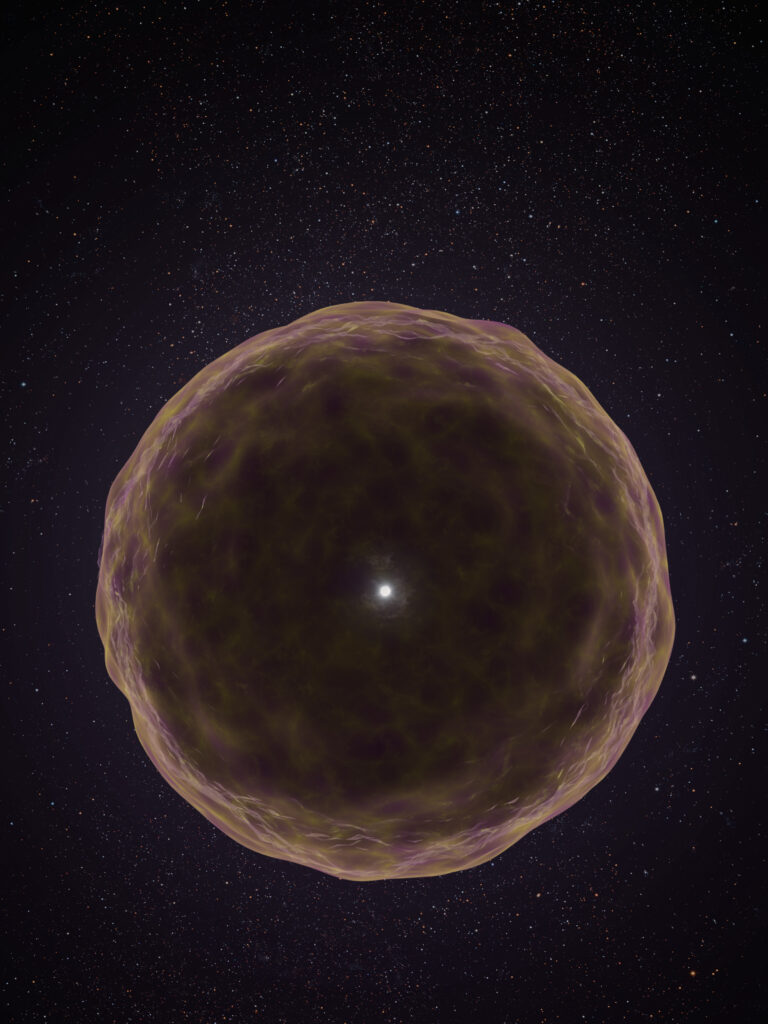

If a supernova erupted near Earth, harmful cosmic rays, which are charged particles that act like tiny space bullets, and ultraviolet radiation would pummel Earth’s ozone layer, eventually tearing a hole through its protective bubble. This scenario has long been considered, but a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that at least one of Earth’s past mass extinctions might have been the result of a nearby supernova.

The crime scene

The Devonian period, which lasted from about 419 million to 359 million years ago, culminated in a mass extinction event. During the Devonian, life on dry land was just getting started, and plants led the way. Meanwhile, marine life was already substantially diverse, earning the period the nickname Age of Fishes.

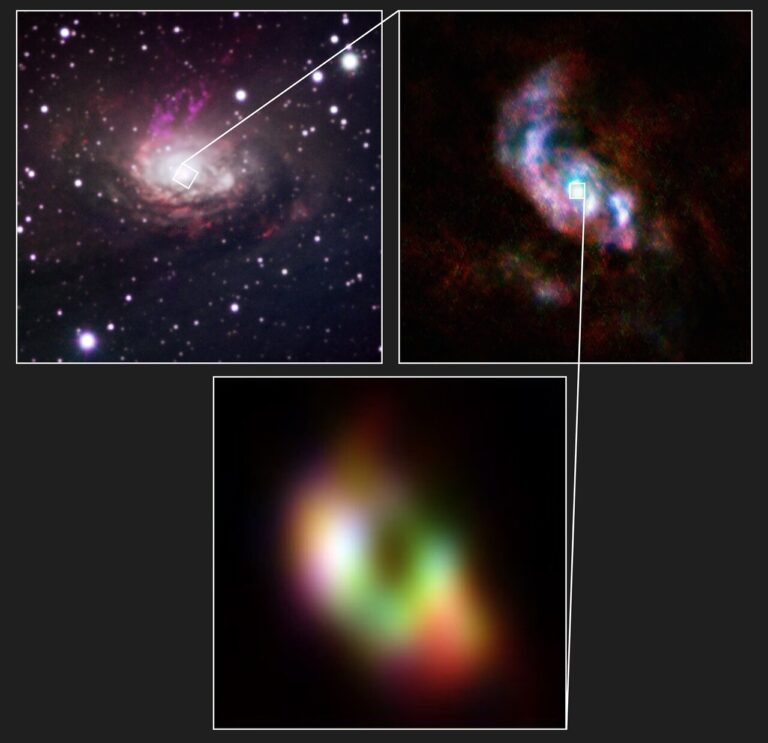

By examining the boundary between the Devonian period and the next (Carboniferous Period) in Earth’s soil, the scientists behind this latest study found plant spores that were burned by ultraviolet light, which suggests they were around when the ozone was depleted. And while numerous calamities can take chunks out of Earth’s ozone, the researchers argue that in this case, a supernova is the most likely culprit.

“Earth-based catastrophes such as large-scale volcanism and global warming can destroy the ozone layer, too,” lead author Brian Fields said in a statement. But the evidence for those scenarios just isn’t there. “Instead, we propose that one or more supernova explosions, about 65 light-years away from Earth, could have been responsible for the protracted loss of ozone.”

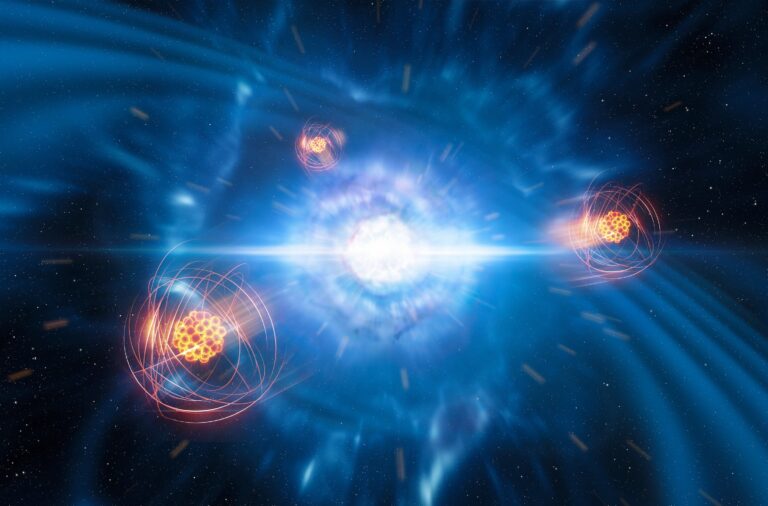

A supernova could indeed deliver just the right attack to devastate life on Earth. Such an explosion would bathe Earth in harmful ultraviolet light, but the damage wouldn’t end there: For up to 100,000 years, supernova debris would continue to rain down on our planet, creating radioactive isotopes in Earth’s atmosphere.

But to complicate matters further, fossil evidence indicates that biodiversity fell for a total of 300,000 years before the final Devonian mass extinction occurred. This suggests that there might have even been more than one supernova that thrashed Earth. “This is entirely possible,” said study co-author Jesse Miller. “Massive stars usually occur in clusters with other massive stars, and other supernovae are likely to occur soon after the first explosion.”

Although the team is still missing conclusive evidence to confirm their theory, they have already outlined what they need to look for. The radioactive isotopes created by supernova debris interacting with Earth’s atmosphere would have decayed long ago. So if researchers can find evidence of these isotopes in rocks from the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary, it would directly suggest that at least one nearby star exploded around that time.

Should we worry about future supernovae extinctions?

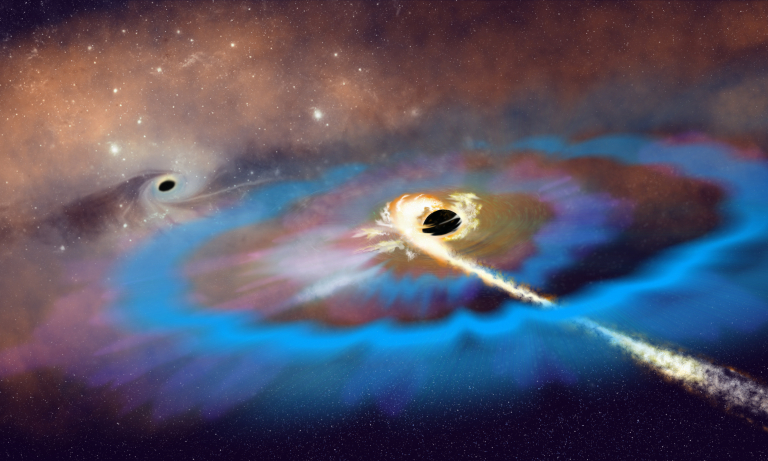

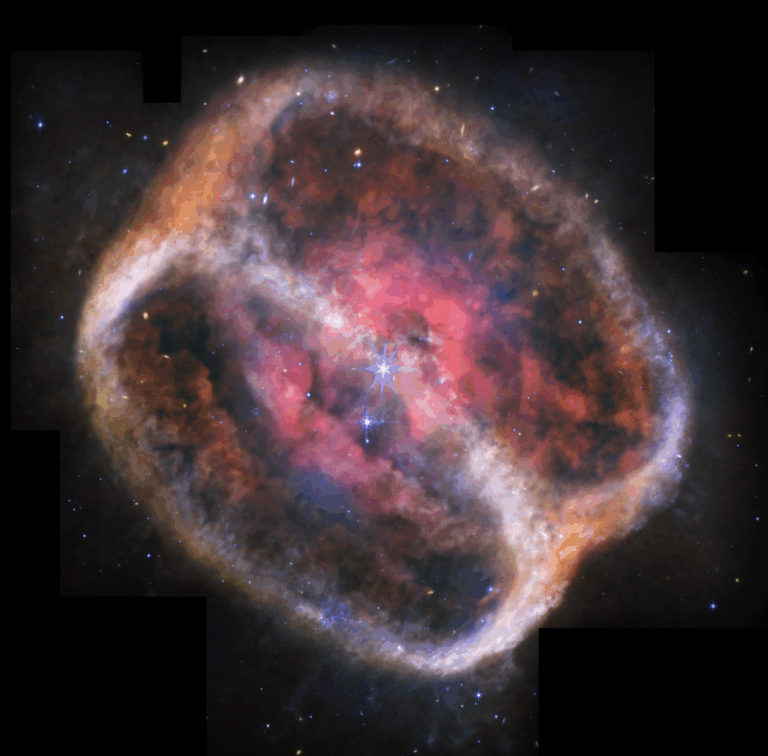

For the most part, Earth has little to be concerned about when it comes to supernovae. At nearly 100,000 light-years across, the Milky Way is a big place. And while experts expect that our galaxy plays host to a supernova about once every 50 years, the last galactic supernovae occurred in 1604. Researchers did closely study a more recent nearby explosion called SN 1987A, but that supernovae occurred in our largest satellite galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud, more than 150,000 light-years away.

At this point, there are a few likely candidates for the next Milky Way supernova, namely, Betelgeuse, Eta Carinae, and Spica. Betelgeuse tends to be seen as the favorite, but its predicted detonation might not occur for up to 100,000 years or so. Located about 650 light-years away, Betelgeuse is far enough away that it won’t be a problem for Earth when it explodes, but it will make for a spectacular view: an explosion as bright as the Full Moon and visible during the day. Eta Carinae, located nearly 7,500 light-years away, also poses no risk. Finally, Spica is the closest know supernova candidate at a distance of just 260 light-years, but it isn’t expected to go supernova for a few million years yet. Plus, Spica still resides well outside the so-called supernova kill distance of 25 light-years.

“The overarching message of our study is that life on Earth does not exist in isolation,” Fields said. “We are citizens of a larger cosmos, and the cosmos intervenes in our lives — often imperceptibly, but sometimes ferociously.”