Key Takeaways:

Move over Mars and make room for Venus: Our inner neighbor has just vaulted into one of the most contentious debates in astrobiology.

On Monday, an international team of astronomers presented evidence that the cloud tops of Venus contain traces of phosphine — a toxic, rancid gas that is produced by microbial life (and some industrial processes) on Earth. What’s more, they say, the chemical’s presence is a mystery. No known non-biological processes can create phosphine in the conditions found on Venus.

If the find is confirmed, it raises the tantalizing possibility that the hellish world may harbor alien life in its weird and mysterious clouds. Alternatively, the phosphine could turn out to be the result of some unknown chemical process, which would be enticing in its own right.

The researchers behind the discovery sought to project a mix of both enthusiasm and restraint when they announced their find during a Zoom press conference on September 14.

“There is a chance we have detected some kind of living organism in the clouds of Venus,” Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University who led the observations, said during the conference. “This is very exciting and was really very unexpected.”

“We are not claiming we have found life on Venus,” MIT planetary scientist and study co-author Sara Seager emphasized a few minutes later. “We are claiming a confident detection of phosphine gas whose existence is a mystery.”

The research wasn’t published until Monday in Nature Astronomy, but word of the news quickly spread through the field during the previous week after the embargoed paper was distributed to journalists.

The discovery puts a spotlight on the prospect of life in the venusian clouds, which was once considered a fringe idea. In addition to igniting much debate, the detection of unexplained phosphine in the clouds of Venus has already spurred more research and unofficial proposals about how future Venus missions could hunt for more signs of alien life.

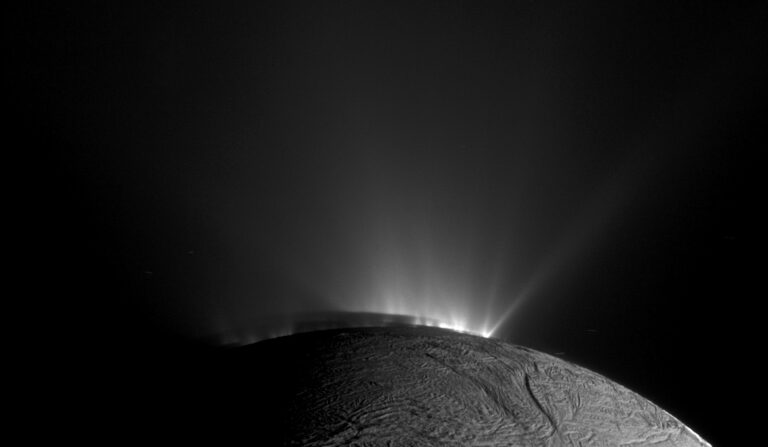

“What’s exciting about the phosphine discovery is that it demands follow-up,” Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at Caltech who was not part of the discovery team, tells Astronomy. “The top three destinations to look for life in the solar system are Mars, Enceladus, and Europa — and now we should perhaps add Venus to the list.”

An aerial ocean

Although the surface of Venus is hot enough to melt lead — nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit, or 480 Celsius — Carl Sagan and Harold Morowitz proposed in 1967 that life could thrive in its clouds. After all, tens of miles above the surface, temperatures and pressures are much more Earth-like.

But that was before scientists discovered just how extreme Venus is. The planet’s clouds are made of at least 80 percent sulfuric acid — a corrosive, deadly compound that’s thousands of times more acidic than battery acid. The idea that life could persist in those conditions, which many have doubted in the past, fell even further out of favor, astrobiologist David Grinspoon of the Planetary Science Institute tells Astronomy. In fact, he adds, “it had kind of almost been forgotten about”

But in recent years, the notion of venusian life has made something of a comeback.

In the early 1990s, NASA’s Magellan probe mapped the surface of Venus with radar, revealing belching volcanoes that feed the world’s sulfuric clouds. These clouds also interact with sunlight, linking the surface, the atmosphere, and the Sun through chemistry and creating a rich cycle of activity that has no other analog in the solar system except Earth. The energy and minerals stirred up in these clouds could provide a temperate niche that’s rich in the nutrients necessary for life, says Grinspoon, who advanced this argument in his 1997 book Venus Revealed.

“The clouds are like the ocean of Venus,” he says.

More recently, scientists have also learned that microbes are more adaptable than once thought. So-called extremophiles can survive and thrive in environments previously considered uninhabitable. Plus, modern climate models have also shown that early in Venus’ history, the planet was a much more inviting, with stable, long-lived oceans on its surface.

“You get this picture where these two habitable — and maybe inhabited — worlds [Earth and Venus] are right next door to each other for billions of years, who knows, exchanging life or evolving in parallel,” says Grinspoon. So, when a runaway greenhouse effect finally overcame Venus and sterilized its surface, perhaps life took refuge in the clouds.

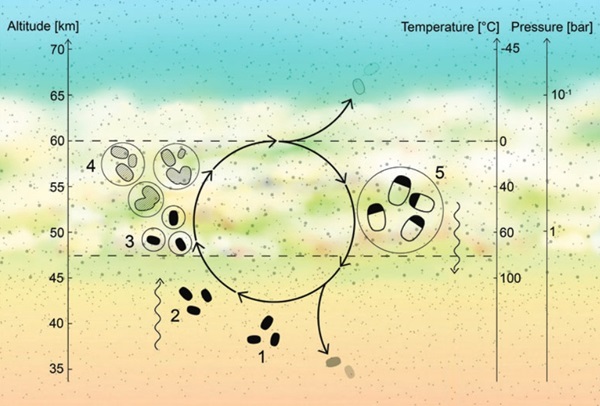

In a paper published last month, Seager and her colleagues proposed a hypothetical life cycle that would allow venusian microbes to survive at altitudes between 30 to 37 miles (48 to 60 kilometers) above the surface. The idea depends on the microbes hibernating as “spores” cocooned inside sulfuric acid cloud droplets, episodically falling to lower cloud layers as acid rain, before later surfing back skyward on updrafts of air.

The proposed life cycle for microbes surviving in the acid clouds of Venus is seen in this illustration. (1) Dehydrated microbes survive in a vegetative state in Venus’ lower haze layer. (2) The spores are lifted by updrafts into the habitable cloud layer. (3) Once encapsulated by liquid, the spores become metabolically active. (4) These microbes divide, and the droplets grow through coagulation. (5) The droplets grow large enough that they sink through the atmosphere, where they begin to evaporate due to higher temperatures, prompting microbes to transform into spores that float in the lower haze layer.

Finding phosphine

Intrigued by the potential for cloud-dwelling life on Venus, in 2016, Greaves set out to search for evidence. She began her quest by researching what chemicals could be detected by radio telescopes. “She dug through the literature and found this very obscure gas that would be a unique biosignature,” Seager said during the conference, referring to phosphine. “It’s so obscure — no one cares about it.”

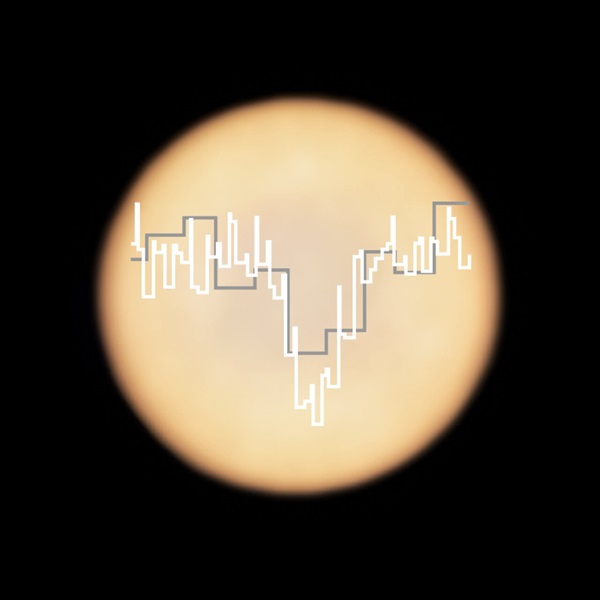

In June 2017, Greaves obtained time on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT), a radio telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii, training it on Venus, which naturally emits radio waves. She hoped to find a dip in brightness at a specific wavelength of light that cloud-borne phosphine would absorb.

“It took about 18 months [of analysis] to convince ourselves there was a signal,” said Greaves. They then followed up in March 2019 with the powerful Atacama Large Millimiter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, which uncovered the same phosphine signal at a higher resolution.

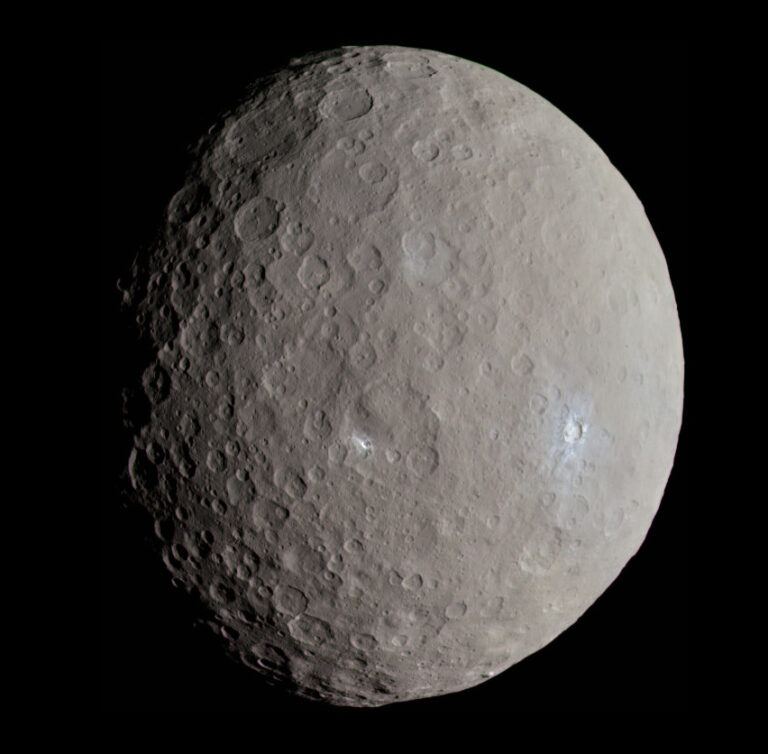

Spectral data from both the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile (white) and the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii (grey) is superimposed on this image of Venus taken by ALMA. Astronomers claim the dip in signal strength is due to phosphine in the clouds of Venus absorbing radio waves.

These independent detections — at a level of about 20 parts per billion — from two different facilities gave the team confidence that the phosphine signal was real. Twenty parts per billion may not seem like a lot, but because phosphine easily breaks down when exposed to the ultraviolet sunlight, the researchers say something must be replenishing it.

So where could phosphine come from?

On Earth, phosphine is generated by microbes in oxygen-free environments that are rather unpleasant by human standards — inside the guts of penguins, for example. Absent of life, the production of phosphine requires great temperatures and pressures, and typically a source of hydrogen to react with. But the team doesn’t think Venus can provide all three. However, phosphine has been detected in the hydrogen-rich atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn, where it’s generated deep inside the gas giants in conditions far more extreme than those found on Venus.

“The presence of phosphine is telling us something interesting,” Ehlmann tells Astronomy. “Either there’s something about the chemistry of Venus’ atmosphere we don’t understand, or — the far more extraordinary claim — maybe there’s a biological source.”

A great debate

Some researchers are skeptical of the detection itself; perhaps the signal is from another chemical masquerading as phosphine.

The paper was initially rejected by the journal Science by referees who objected to the data analysis, says Seager. But, she adds, the techniques the team used were standard to radio astronomy. (It’s worth noting that a journal rejection in and of itself arguably says little, as the list of papers rejected by prestigious journals that eventually won Nobel Prizes is rather extensive.)

Compounds typically absorb at numerous wavelengths, and together, they create a unique, recognizable chemical fingerprint. However, the team has identified phosphine by absorption at only a single wavelength — one that is also shared by sulfur dioxide.

This gives some researchers pause.

“As a geochemist, I always worry about detection from one peak,” says Justin Filiberto, a geochemist at LPI. “A single line is a coincidence, not a detection,” adds Kevin Zahnle, an astrobiologist at NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California.

The team behind the new find agrees that more phosphine lines should be sought to confirm its presence. But they also argue they can rule out sulfur dioxide based on their current observations. If it were a signal from sulfur dioxide, they say, other spectral lines should have been present, which they did detect.

This is convincing to some. However, “I’m told there has been much skepticism, including from journal referees, about the detection,” tweeted Chris Lintott, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford and host of the BBC’s program The Sky at Night. “JCMT and ALMA were not made to look at things as bright as Venus and this is a difficult observation.”

But Greaves and radio astronomers Anita Richards of the University of Manchester “know JCMT and ALMA very well,” Lintott added. “I’d bet the detection is real.”

Modeling mysteries

If the phosphine detection is confirmed, could there be some non-biological process that’s missing from the team’s models that could explain it?

The researchers tried modeling the complex atmospheric chemistry of Venus to see if they could explain the levels of phosphine they detected. But they could only reproduce a signal about a thousandth as strong as what they observed. More exotic ideas fell short, too, including lightning and meteorites. (The details of their full modeling analysis, led by MIT’s Williams Bains and Janusz Pekowski, are being published in a separate paper currently going through peer review.)

The team also argues that observed volcanic activity on Venus can’t account for all the phosphine. However, Filiberto thinks that conclusion may be premature.

He has co-authored two papers in the last year reporting evidence of fresh lava flows on Venus’ surface. That would mean the planet “is a lot more volcanically active than we thought,” he says. “And we don’t know what gases are coming out of those volcanoes.” (An independent team at ETH Zurich and the University of Maryland reported further evidence of venusian volcanism in July.)

These volcanoes could be pumping phosphine directly into the atmosphere, Filiberto says. They could also be belching hydrogen, which might allow phosphorus acid from the atmosphere to react and form phosphine, thanks to the high temperatures near the surface. “I don’t think we can discredit this at this point and say it can’t be volcanoes, or at least that there can’t be a volcanic contribution,” he says.

There’s also the intriguing possibility that the chemistry of Venus is simply stranger than expected.

“The team, I think, did a nice job in kind of presenting a set of first-order models,” says Ehlmann. “But now we can dig a little deeper and consider weird chemistry.” For instance, she says, perhaps the modeled chemical reactions behave differently in Venus’ extremely acidic environments, or maybe air moves between atmospheric layers in unexpected ways.

Then again, maybe the chemistry isn’t even really that strange, given how little we know about surface conditions on Venus. “Phosphine is easy to make,” tweeted Lee Cronin, an inorganic chemist at the University of Glasgow. “Rocks [could] get thrown into the air by some process and react in the atmosphere,” he added. “There are just so many…possible options.”

There’s also the possibility the phosphine is coming from a totally unknown source. Sarah Hörst, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University, likewise took to Twitter to point out that in the early 1980s, astronomers detected carbon monoxide on Saturn’s moon Titan. Models failed to explain that find for decades. Then in 2008, the Cassini mission discovered that another Saturnian moon, Enceladus, had cracks on its surface that were spraying water into space, effectively injecting it into Titan’s atmosphere. Researchers hadn’t included that possibility in their models.

“The less you know about an atmosphere,” Hörst tweeted, “the harder it is to use a model to draw conclusions about it, and the more careful you have to be about how you use it.”

For now, the team behind the phosphine detection is letting the rest of the community digest their work, as well as waiting to see if someone else can explain it.

“When I first heard about it, honestly, I was very skeptical too,” says Seager. When the team’s models failed to find a non-biological explanation for the phosphine, she admits to having mixed feelings. “Dare I even say, we wanted it to go away,” she says. “Like, no one wants to be out there claiming there’s life.”

“And when we got better data,” Seager adds, “eventually I had to [say], ‘Wow, this is real.'”

Now that the work is out there, the team is prepared — even eager — for other researchers to challenge their assumptions. But so far, Seager thinks many of the critiques being raised are already addressed by the team in their analysis.

“The team has had years … to digest this, and to criticize, and to work through our self-criticism,” she says. “We’ve had reviewers take months to give us more criticisms. So, we’ve had a long time to sort of cycle through all these. It’s been interesting, watching everybody trying to digest this in a day or two, right? All their questions are legit and natural, but they do need to read the paper.”

Mission to Venus?

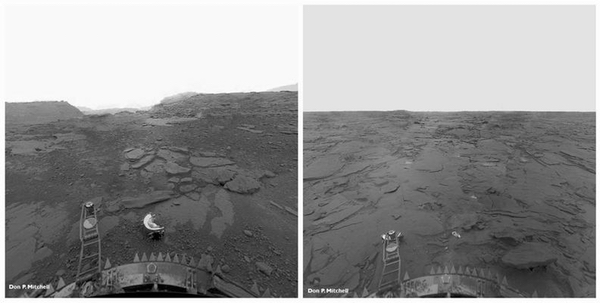

Many scientists argue the most straightforward way to definitively confirm phosphine is to go to Venus and sample it. And fortunately for Venus exploration advocates, a flurry of potential mission are already being planned.

NASA has funded a team to study the concept of a flagship mission to Venus that would include balloons that float through the atmosphere, similar to the European/Russian Vega missions in 1985. The team’s mission concept will be considered as part of the ongoing Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey — a once-a-decade process that outlines the field’s consensus on funding priorities for the next 10 years. A strong recommendation from the Decadal Report, due out by March 2022, is the surest path for NASA to greenlight a Venus mission.

The space agency is also currently considering two proposals that target Venus as part of its low-budget Discovery-class mission program: an orbiter called VERITAS and an atmospheric probe called DAVINCI+. Fillberto, who is a member of the DAVINCI+ team, says the probe could directly detect phosphine as it descends through the dense venusian atmosphere.

NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine also seemed to throw his weight behind Venus exploration on Monday, tweeting “It’s time to prioritize Venus.” Bridenstine went on to call the discovery of phosphine on Venus “the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth.”

But it’s not just NASA and academia who have their sights set on Venus; private organizations do, too. Breakthrough Initiatives, a foundation focused on the search for extraterrestrial life created by Russian tech magnate Yuri Milner, announced on Tuesday it was funding a team led by Seager (including Ehlmann and Grinspoon, among others) to investigate the possibility of sending a new mission to Venus.

The effort is still in the earliest of stages, with a formal kickoff meeting set for September 18. And although the team members signed up for this mission development project a while back, Seager says she couldn’t tell them about the phosphine paper until just before it was published.

Seager’s team also has been talking to the private space company Rocket Lab, which had been independently pursuing their own missions to Venus, with ambitions to launch as soon as 2023. When Rocket Lab got word of the phosphine detection, the company and its CEO Peter Beck even offered to give Seager’s team a lift there.

Rocket Lab’s booster is designed for small satellites, so their spacecraft would be smaller in scale than a NASA flagship mission. But a fast, cheap, and targeted mission could beat the NASA missions by years.

And besides, Ehlmann says, “you don’t need a Cadillac spacecraft to do good Venus science.”

While detecting venusian life itself would be challenging, detecting organic molecules — a strong indicator of life — “is actually not that tricky. You can do that measurement relatively straightforwardly. You just need sufficient time in the Venus atmosphere.”

Grinspoon, however, is reluctant to push phosphine as the sole motivation for a mission to Venus before the detection has undergone more scrutiny.

“But, certainly if it does stand up,” he says, “then hell yeah, we gotta go and see what’s going on there.”