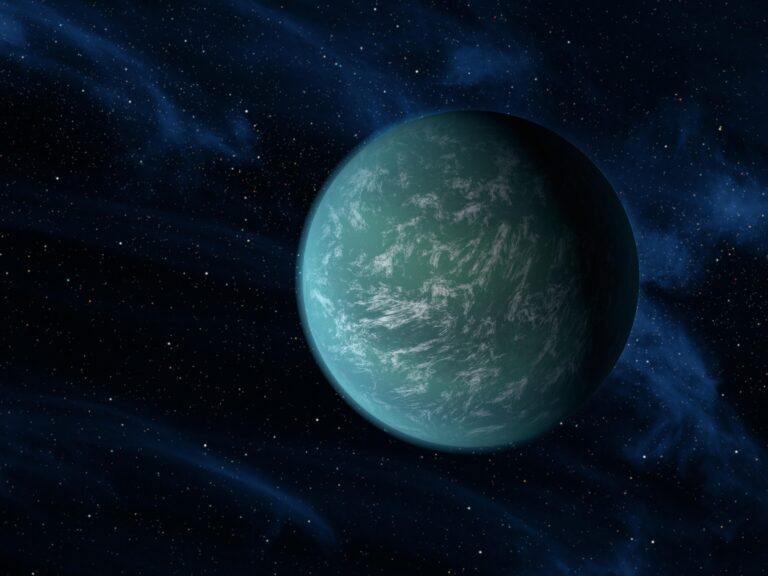

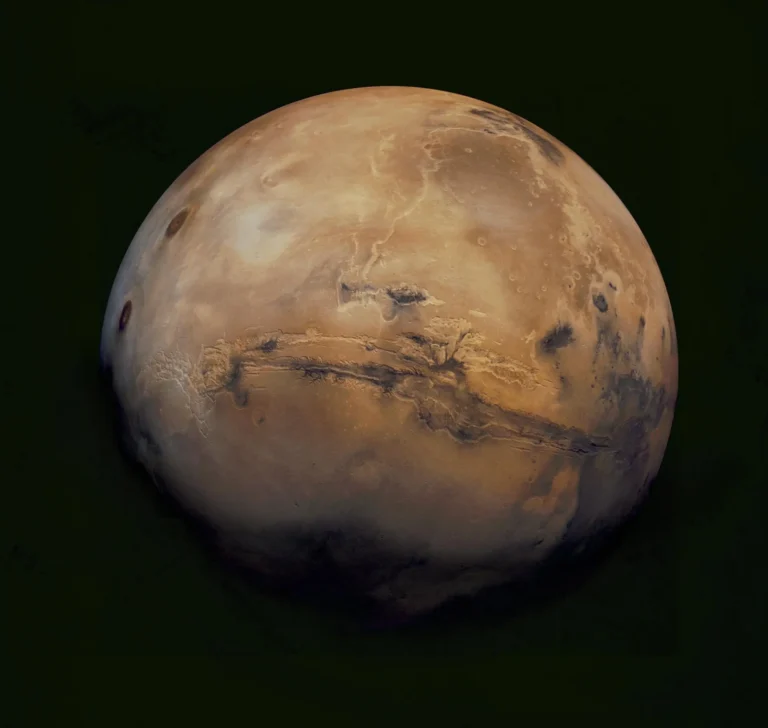

Water. Energy. Chemistry. Europa has all the necessary ingredients for life. And unlike Mars or other potentially habitable worlds, Jupiter’s icy moon doesn’t have just a little water — it boasts twice as much of the liquid as Earth’s oceans combined.

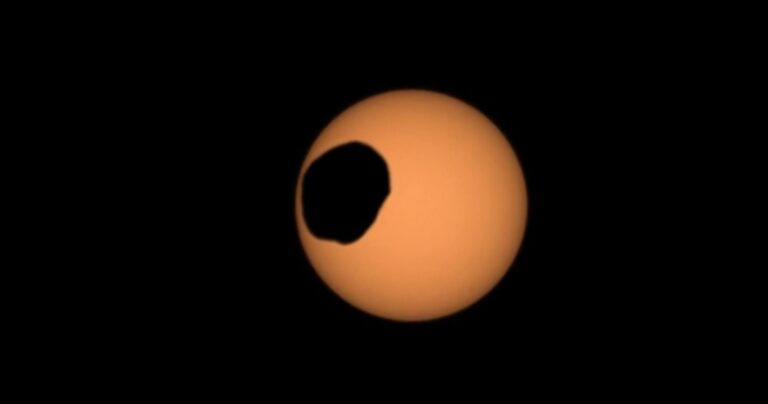

Despite Europa’s deep-space locale, the moon doesn’t completely freeze because Jupiter’s hulking gravity heats up its core. As the most massive planet in the solar system, Jupiter constantly tugs on Europa, creating tides and, potentially, hydrothermal vents that can mix up life-enabling chemical cocktails below the moon’s icy shell.

All that water, heat, and mixing makes Europa one of the most promising places to find alien life in our solar system. And that’s why NASA is building a dedicated mission to the ocean world called Europa Clipper.

The primary goal of Europa Clipper is to find out if the moon is actually habitable. And in just a few short years, around 2023, the spacecraft will be ready for launch. So, less than a decade from now, depending on the space agency’s final rocket choice, Europa Clipper should reach its destination.

Once there, the spacecraft’s instruments will search Europa’ surface and “taste” its thin atmosphere, looking for signs of recent eruptions of water. The mission also should reveal secrets of the moon’s icy shell and aqueous interior, despite never touching down on its surface.

Those insights will be vital to taking the next step: Landing a spacecraft on Europa.

“The Europa Clipper mission will take a profound step in advancing our understanding of habitable environments beyond Earth,” wrote NASA’s Samuel Howell and Robert Pappalardo, both Europa Clipper team members, in the journal Nature Communications earlier this year.

The push for a Europa mission

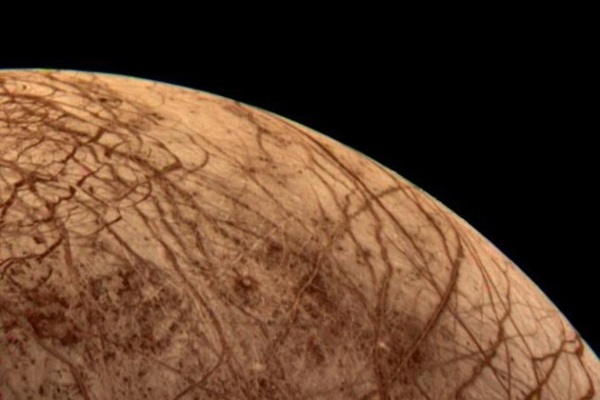

In July 1979, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft returned the first close-up images of Jupiter and its moons. This brief flyby was enough to thrill astronomers. The probe’s grainy images revealed Europa was covered in a young, icy crust, but it would take more than a decade before another spacecraft visited the fascinating moon.

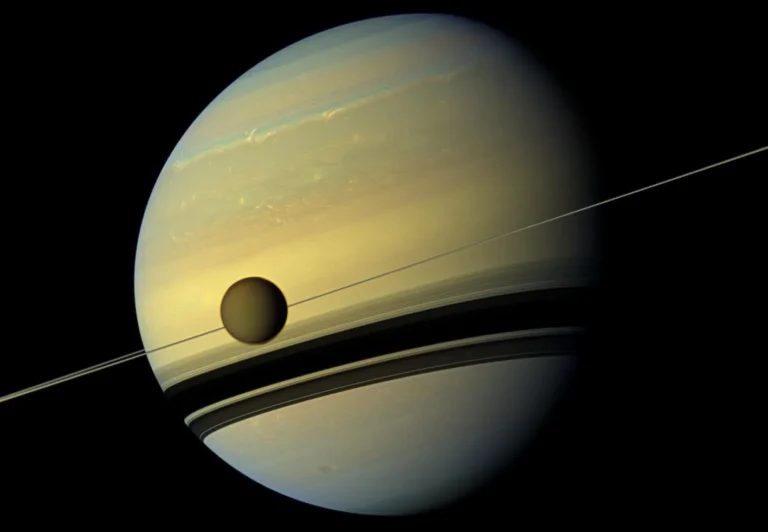

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, a Jupiter-orbiting satellite that launched in 1989, provided the follow-up. But Galileo didn’t operate entirely as expected thanks to a malfunctioning antenna. It only gathered a limited dataset, making about a dozen close flybys of Europa.

Nonetheless, Galileo discovered that Europa has an induced magnetic field, which led them to detect its global saltwater ocean. Those glimpses also showcased the moon’s complex geology, including a detailed look at its cracked and chaotic surface. As the last mission to perform detailed studies of Europa up close, scientists still depend on Galileo’s three-decade-old data to make breakthroughs today.

In fact, in a paper published in Nature Astronomy in 2018, researchers used old Galileo data to find the best evidence yet for plumes of water ice streaming off Europa. The team behind the study looked at changes in the moon’s magnetic field and plasma and traced back where the spacecraft was when it saw them. It turned out, the observations focused on an area already suspected to have heat welling up from Europa’s interior.

And despite limited up-close data of Europa, astronomers have been able to make some new discoveries from roughly 400 million miles away. On multiple occasions, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has spotted evidence for plumes of water erupting from Europa’s ocean out through the icy shell and into icy space.

Meanwhile, models suggest that Europa could also hide the kind of hydrothermal vents that fuel entire deep-ocean ecosystems on Earth. Some research even hints that the moon’s ocean could have an Earth-like chemical balance capable of supporting life, even without hydrothermal vents.

All of these results only make astronomers want to return to Europa more than ever.

Building Europa Clipper

Soon, they’ll have their chance. Last year, NASA formally announced that Europa Clipper would move into its final design phase, the last step before actual construction and testing begins. And it could even launch as soon as 2024, if it’s ready in time.

The mission’s driving purpose is to find out whether the conditions for life could exist on Europa. To do this, the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter on a long, looping path that allows for 45 flybys of the icy moon. Some passes will take the spacecraft within just 16 miles (25 km) of Europa’s icy surface.

Such an ambitious path proved pivotal to the mission getting funding, too. In the past, scientists had proposed Europa spacecraft that orbited the moon itself. But at Europa’s distance, Jupiter emits intense radiation. A Europa-orbiting spacecraft would need serious shielding to endure prolonged exposure to this harsh environment. and the cost of providing that protection proved too much. So, after several failed mission proposals, engineers finally came up with an alternative path to explore Europa. By relying on long, elliptical loops around Juipter, the Clipper mission limits the amount of radiation it’s exposed to, which helped reduce cost.

Despite gathering fewer views of Europa’s surface than if it orbited the moon itself, the science the spacecraft performs will still be a game-changer.

Europa Clipper has nine instruments, ranging from high-resolution cameras that will offer detailed views of the surface, to ice-penetrating radar that will let astronomers gauge the thickness of Europa’s frozen shell. A gravitometer will confirm that Europa’s ocean exists, plus other details, while a spectrometer will allow scientists to suss out the chemical fingerprints of specific types of ice on the moon, revealing what mix of elements spill onto the surface from the ocean below. The mission will also carry a magnetometer. By studying the world’s magnetic field, astronomers hope to get a better grasp on the depth and salt content of Europa’s oceans.

Taken together, Europa Clipper’s instrument suite should revolutionize our understanding of the ocean moon — not just on the outside, but on the inside, too.

The mission’s biggest lingering question is how exactly it will reach its target. Europa Clipper could arrive around Jupiter anywhere 2.5 to 6 years after launch, depending on which rocket the mission relies on.

When the U.S. Congress was debating Europa Clipper, legislators secured key votes to approve funding by requiring the spacecraft fly atop NASA’s long-delayed and much-maligned Space Launch System. The rocket is being built in Alabama, where it provides jobs for the constituents of certain senators and members of congress. But after years of delays, it’s still never flown. NASA itself has suggested not using the rocket because it’s massively more expensive than other options, like SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV rockets.

Plus, Europa Clipper has already had to make cost cutting decisions due to budget overruns, as reported by the website SpaceNews. So, ultimately, getting Europa Clipper off the ground on schedule and on budget could require new legislation.

Laying the groundwork for a Europa lander

Europa Clipper’s launch vehicle wasn’t the only choice that congress mandated by law, either. The space agency also is required to later send a lander to Europa, something it’s so far been reluctant to commit to.

“NASA’s a big bureaucracy. It’s difficult to get them to move or do things, so it was necessary for me to write it into law,” former Congressman John Culberson of Texas told Astronomy in 2015. “In fact, [this] is the only mission that it is illegal for NASA not to fly. And I made certain of that.”

Undoubtedly, Europa’s underground ocean is its most interesting feature. And if there’s life on the world, it’s likely beneath the surface. But getting down there will not be easy. In the past, scientists have suggested landing probes on the surface that could melt through miles of ice and deploy submarines to explore the vast oceans.

Sending a lander would be expensive and technologically challenging, however. And more importantly, though NASA makes valiant efforts to avoid it, the spacecraft could carry earthly lifeforms with it, compromising any data and possibly bringing invasive microbes to a pristine alien environment.

That’s part of the reason why, despite the legal requirement, NASA has yet to formalize a plan to build a Europa lander. However, the scientific community has since proposed a number of potential options to explore Europa’s surface — as well its ocean below.

In the meantime, Europa Clipper will rely on other ways to measure the composition of the moon’s water and note places where it interacts with the surface. And that work should pave the way for the future of exploration. Once astronomers better understand the internal workings of the icy moon Europa, they’ll be able to choose the best place to take a peek inside and search for signs of life.

“Why would we go all that way and not answer the single most important question: Is there life on another world?” Culberson said. “Well, the only way you answer it is with a lander, and that’s the consensus of the scientific community. I’m convinced they’re right.”