These signs are called biosignatures. Earth’s atmosphere contains high levels of oxygen and ozone, highly reactive molecules that should have long ago reacted with other compounds and disappeared if they were leftovers from the formation of the Solar System. Instead, their presence suggests that something on Earth’s surface is producing them in prodigious quantities. The same is true of methane, which breaks down easily in sunlight.

Another is phosphine, a toxic, flammable gas with a characteristic smell of garlic or rotting fish. Phosphine is highly reactive and so survives for only a short time. Its presence in Earth’s atmosphere at the level of parts per trillion suggests it must be constantly produced, in this case by anaerobic bacteria.

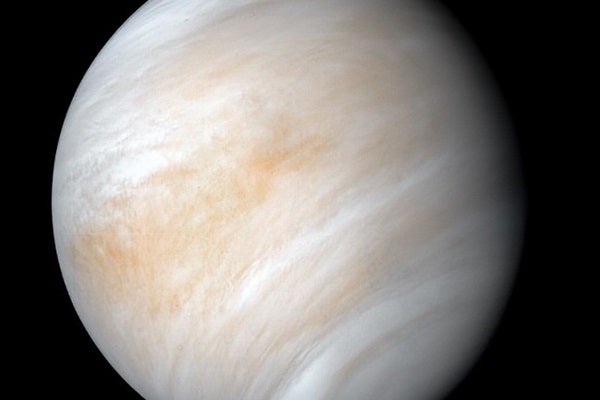

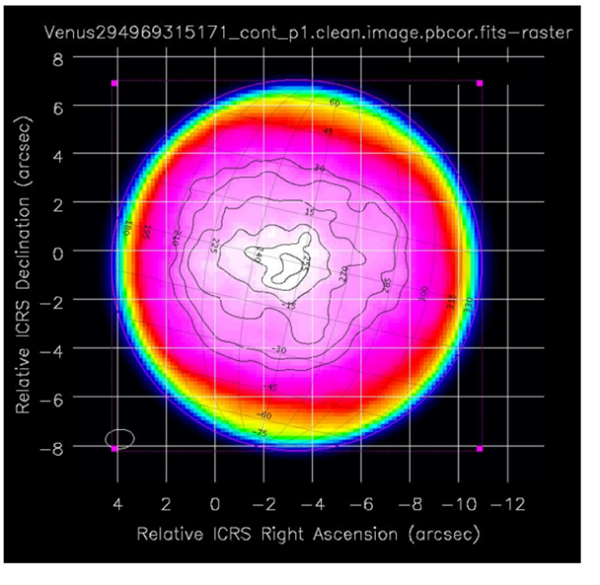

That’s why the discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus at parts-per-billion levels made headlines this week. Jane Greaves from the University of Cardiff and colleagues say there is no known way for phosphine to be produced on Venus by known geochemical or photochemical processes. This raises the possibility that biological processes could be responsible.

“The presence of even a few parts-per-billion of phosphine is completely unexpected,” they say. That suddenly makes Venus much more interesting and raises the stakes for future mission planning.

Interplanetary mission

Interestingly, Venus and Earth aren’t the only planets with phosphine in their atmospheres. Earlier this century, the Cassini spacecraft spotted phosphine in the upper atmospheres of both Jupiter and Saturn.

In these cases, the gas is created in large quantities deep within these planet’s atmospheres where the temperature is well above 1100 Kelvin. It then leaks into the upper atmosphere through upwelling and convection, where it is quickly broken down by sunlight and other chemical processes.

So an important question is whether a similar process could have created the phosphine on Venus. Greaves and co study this question in detail and say that the temperature on Venus — a mere 740 Kelvin — simply isn’t high enough to allow the same chemical pathways that occur in the gas giants.

Indeed, the team considered a huge variety of chemical pathways under a wide range of conditions for forming the gas. “We find that PH3 formation is not favored even considering ~75 relevant reactions under thousands of conditions encompassing any likely atmosphere, surface or subsurface properties,” they say.

But it also raises the possibility of more exotic explanations. Many of the team involved in the discovery have studied phosphine as a biomarker for some time. In a paper published last year, they said, “We find that phosphine is a promising marker for life if detected on a temperate exoplanet.”

So how much phosphine is being produced on Venus? Given the measured concentration of a few parts per billion, the key factor is how long it lasts in the atmosphere.

The team say that at altitudes above 80 km (50 mi), phosphine is likely to be broken down in a few minutes by reactions driven by sunlight. At low altitude, the main method of decomposition is by heat.

But at 50km (31 mi), the Venusian atmosphere is relatively pleasant and so where phosphine is likely to be concentrated. “The lifetime of phosphine in the atmosphere is thus no longer than 1,000 years, either because it is destroyed more quickly or because it is transported to a region where it is rapidly destroyed,” they conclude.

That implies that phosphine must be produced at the rate of millions of molecules per second per square centimeter.

So what kind of processes could do this? One possibility is volcanism, which can inject phosphorous into the atmosphere. But Greaves and co say this would only be possible if Venus were 200 times more volcanically active than Earth, which it doesn’t appear to be.

Lightning can produce the conditions necessary to make phosphine, but the atmosphere is not active enough for this, by several orders of magnitude. And meteor impacts dump several tons of phosphorous into the atmosphere every year, but not nearly enough to explain the observed levels of phosphine.

Habitable zone

Life, of course, is the explanation of last resort. This would have to be an airborne ecosystem at temperate altitudes. “The mid-latitude Hadley circulation cells offer the most stable environment for life, with circulation times of 70-90 days,” say the researchers.

That still requires some explaining. The Venusian atmosphere is highly acidic. So any form of life would need to be able to cope with this in some way, perhaps covered with a tough protective layer, or perhaps able to exploit the acidity. There are numerous unanswered questions.

That makes Venus a much more important target for future visits. The U.S. and Russia have explored plans to send a lander and orbiter to the planet in 2026 or 2027. The European Space Agency has proposed to visit in 2032. And the Indian Space Research Organization has a mission scheduled for 2023.

The possibility of finding life will be an important driver for these missions but there is an even more pressing reason to go. Planetary geologists recently concluded that the surface of Venus may have supported liquid water for many billions of years, perhaps until as recently as 700 million years ago. It then suffered a catastrophic greenhouse effect, which left it with a surface temperature hot enough to melt lead.

Understanding what went wrong will be crucial in preventing a similar catastrophe on Earth. That’s the real reason why NASA, ESA and other space agencies must turn their attention urgently to Venus. We do not have time to spare.

Refs: Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus arxiv.org/abs/2009.06593 Phosphine as a Biosignature Gas in Exoplanet Atmospheres arxiv.org/abs/1910.05224