Key Takeaways:

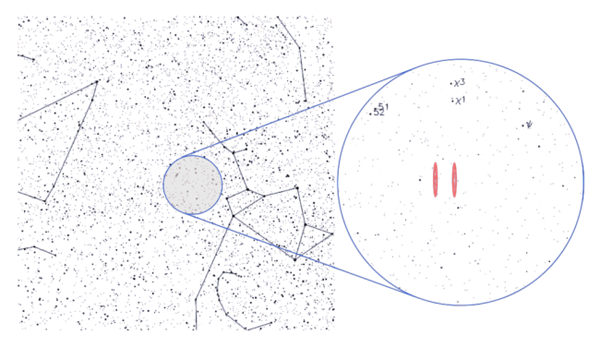

- The Wow! Signal, a strong, narrowband radio signal detected in 1977 by the Big Ear Radio Observatory, remains unexplained, despite subsequent searches of the originating region in Sagittarius.

- The signal's unique characteristics—its intensity, brevity, and lack of recurrence—fueled speculation about extraterrestrial origins, yet its detection predated real-time analysis capabilities, hindering immediate follow-up observations.

- The Big Ear's limited computational power and subsequent decommissioning prevented thorough investigation, contributing to the enduring mystery surrounding the Wow! Signal.

- While public fascination with the Wow! Signal persists, professional astronomers view it as one among many similar, one-off signals detected before real-time follow-up technology became common, reducing the frequency of such unexplained events.

Few moments in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) have captivated the public’s imagination quite like the Wow! Signal. To some, it’s the most promising potential detection of alien life ever. But others see it as a triumph of publicity over science.

“Was that E.T. or was it not E.T.? Nobody knows,” Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI Institute, tells Astronomy. “Nobody has ever found another explanation for what that might have been. It’s like you hear chains rattling in your attic and you think ‘My god ghosts are real.’ But then you never hear them again, so what do you think?” Most importantly, Shostak says that if the signal wouldn’t have had Wow! written across it, no one would’ve ever heard of it. One-off signals like this were common back in the early days of SETI, when observatory computers were too primitive to notify astronomers of discoveries in real time, or perform rapid-fire follow-ups.

But that hasn’t stopped astronomers from repeatedly returning to this patch of sky searching for the return of the Wow! Signal.

A strange signal from Sagittarius

Late in the summer of 1977, Jerry Ehman sat down to review the latest batch of computer printouts detailing data collected by the Big Ear Radio Observatory, where he was volunteering as an astronomer. The observatory was controlled remotely, and it could collect several days worth of data before the computer ran out of storage space. At that point, a technician would show up, reset things, and start the next observing run focusing on a new patch of sky.

The Big Ear Radio Observatory was well known among astronomers in its day. The telescope was designed by pioneering Ohio State University radio astronomer John Kraus. And it was largely built by university staff, volunteers, and part-time laborers in the 1960s. Originally, it was constructed with funds from the National Science Foundation funds to carry out the dedicated task of creating the most accurate radio map sky ever.

However, after Big Ear completed mapping the radio sky in 1972, the telescope needed a new task.

Beginning in 1973, NASA agreed to fund a largely volunteer-staffed effort to search the sky for radio signals from technologically-advanced aliens. Besides the professional astronomers behind the project, a group of doctors, lawyers, school teachers, and college professors from totally unrelated professions also pitched in over the decades.

“We were operating on a shoestring budget,” Ehman told Astronomy in 2016. “We didn’t have the money to pay folks, which is why those who were involved were volunteers.”

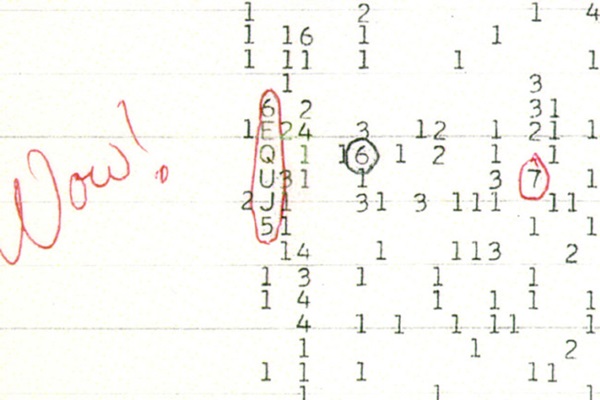

To the untrained eye, it looks like nonsense. But to Ehman, the data meant that Big Ear had picked up a very strong signal that started out low, increased in strength, and then dropped off again. That meant the signal was likely picked up as one particular region of sky passed over the detector. It wasn’t earthly. The signal also only appeared in one of 50 possible channels.

“It was a narrowband signal, just what we were looking for [with SETI],” Ehman said. “It didn’t take long for me to recognize that this was extremely interesting. And the word ‘Wow!’ came to my mind very quickly, so I wrote it down.”

But as he poured through data from the following days, he was surprised to find the signal didn’t reappear. His intrigue only deepened after meeting with the observatory director and staff. Together, they searched the sky for any possible objects in that region of the sky that could explain the signal. The astronomers checked everything from comets and planets to satellites and more. Nothing matched up.

The team kept Big Ear observing that same celestial spot for a month, yet they found nothing. And a year later when they tried again, they still came up empty. The SETI project at Big Ear ultimately lasted for 24 years, making it the longest-running continuous SETI search in history. But during that time, the investigators never picked up anything else quite like the Wow! Signal. For Ehman’s part, he also maintains that we may never know exactly what he discovered that day.

“No conclusion was ever possible other than it certainly had the potential of being a signal from extraterrestrial intelligence,” Ehman said.

In the end, Big Ear’s death came just a few years after Congress deemed the search for extraterrestrial intelligence unworthy of taxpayer funds in 1993. The observatory lost its $100,000 in annual funding from NASA, plus another $50,000 slated for an instrument that could’ve given Big Ear a new lease on life.

By 1998, Ohio State University had demolished the telescope.

Wow follow-ups

Over the years, many other astronomers have followed-up on the Wow! Signal, either trying to explain it away or relocate it. But to astronomers like Shostak, the signal is really just one of many similar detections made over the years.

“In those days, it was very common to pick up these kinds of signals just one time,” Shostak says. “Computers didn’t have the power to do real time follow-ups. If you picked it up today, the comp would say ‘Wow!,’ and astronomers would start nodding the telescope in the direction of the Wow! Signal to try to figure out what it was.” Once observatory computers became sophisticated enough for real-time follow-ups, the number of mystery signals dropped. “The aliens knew we had better equipment,” Shostak jokingly says.

For example, in the past few years, astronomers have discovered fast radio bursts (FRBs), which were initially seen as strong radio signals that appeared just once. The discovery of FRBs, as well as the progress made tracking down their origins, has been one of the biggest recent breakthroughs in astronomy.

Meanwhile, Shostak sees the Wow! Signal fixation as something the public is interested in far more than astronomers are.

“I get emails at least once a month from people who look at that printout and interpret those data in all sorts of ways,” he says. People often see it as an alien code that’s being sent as a direct message to humans. They don’t realize the combination of numbers and letters on the printout was just a convention set by [human] astronomers working at the observatory. The printouts couldn’t handle numbers larger than nine, so the display cycles through letters, starting with “B,” for each increasing order of intensity.

“People think they’ve figured out what the message is or how big the aliens are,” Shostak adds. “And it’s like a dozen numbers, and all that printout does is give you the level of intensity.”

But even if it was humanity’s first message from aliens, Ehman still doesn’t have a guess at to what it could have said.

“Who knows?,” he says. “I have no idea what might have been contained in the message, if anything.”