Key Takeaways:

- The article details the upcoming deployment of four next-generation telescopes: the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), each significantly larger than existing telescopes.

- These telescopes utilize advancements in mirror technology, including monolithic casting and segmented mirror designs, alongside adaptive optics to mitigate atmospheric distortion, enabling enhanced light-gathering capabilities and resolution.

- The increased capabilities will facilitate deeper observations of fainter objects, higher-resolution imaging, and improved spectral analysis, enabling investigations into diverse astronomical phenomena such as exoplanet characterization, star formation and death, galactic evolution, and the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

- The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's unique feature is its rapid, wide-field imaging capabilities, enabling a comprehensive time-domain survey of the sky, ideal for detecting transient events and creating a detailed census of solar system objects.

History repeated itself starting in 1949, when the 200-inch Hale Telescope took its first photograph of the night sky. In the early 1960s, astronomer Maarten Schmidt used the instrument to analyze unusual, “quasi-stellar radio sources”— quasars for short. These turned out to be supermassive black holes accreting matter in the centers of galaxies, a science-fiction fantasy when the Hale Telescope was built.

By the 1990s, technology advanced far enough to usher in an era of telescopes 8 to 10 meters across (26 to 33 feet), and the same story played out once more. With an essential assist from the 2.4-meter Hubble Space Telescope orbiting above Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere, these instruments could analyze a few dozen distant Type Ia supernovas — the cataclysmic explosions of white dwarf stars. Shockingly, researchers discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. Again, this was only possible with the increased firepower of the latest telescopes.

Now, astronomers stand on the threshold of a new telescope revolution. During the next several years, researchers expect three instruments that are more than twice the size of their closest competitors to start scanning the skies. And a fourth telescope, one “only” 8 meters in diameter, will use advanced technology to image the entire night sky every three days.

This quartet of new instruments promises to deliver stunning science on the hot-button issues. But, as with the previous great leaps forward in size, the new scopes likely will also make discoveries that no one can yet envision. As Pat McCarthy, vice president of the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) Organization, puts it: “We expect to learn things we don’t know.”

Size matters

Astronomers are always looking to stretch boundaries — to see fainter objects in greater detail. A bigger telescope collects more light, and so allows a deeper view of the cosmos. Double the diameter of the main mirror gathering light for the telescope and you’ve quadrupled its surface area, and thus the amount of light it gets. An observation that once took four hours can now be accomplished in one, and this same mirror will let you see roughly twice as far away.

Well, professional astronomers don’t live by imaging alone. More often than not, they need breakdowns of light, called spectra, of the things they observe, to tease out information about an object’s temperature, velocity, rotation and composition. Indeed, a spectrum is the only way to distinguish starlight from a glowing gas cloud, or a faint star in the Milky Way’s vicinity from a fuzzy galaxy in a distant corner of the universe. And to get enough light to do even a minimal amount of spectral analysis takes about 100 times longer than getting an image does. Luckily, bigger scopes allow that processing time to come down significantly.

Resolution also increases with a telescope’s diameter. Make a mirror twice as wide and it delivers twice as much detail. And thanks to a quirk of physics, you can reap the same benefit by placing smaller telescopes farther apart and then combining their light, through a process known as interferometry. (Radio astronomers using this technique produced the first image of a black hole earlier this year: A global network of radio telescopes saw across about 54 million light-years to capture the supermassive black hole at the center of the giant galaxy M87.)

Ground-based telescopes face an additional challenge: Earth’s detail-destroying atmosphere. As light from a celestial object passes through air at different temperatures, it gets jostled about and loses clarity. That’s a big reason why designers place large telescopes on high mountaintops — there’s far less air above them to interfere. Even temperature differences between the air outside and inside a telescope’s dome can generate air currents that adversely affect an image’s sharpness.

That’s where adaptive optics comes in. In the past few decades, astronomers have honed this technique, which mechanically compensates for any atmospheric shenanigans and

delivers images nearly as sharp as the mirror can theoretically produce. The heart of an adaptive optics system is a thin, flexible, computer-controlled mirror. Astronomers target a fairly bright reference star close to the object they want to study. The computer analyzes the incoming light to measure how the atmosphere blurs it, then tells the control system how to adjust the mirror’s shape to correct the image in real-time. Because atmospheric turbulence changes constantly, such systems can alter the mirror’s shape up to 1,000 times each second. And if no bright reference star lies nearby — as often happens — astronomers can simply shine powerful laser beams into Earth’s upper atmosphere and create their own reference light.

Making mirrors

Before they can take advantage of the next generation of telescopes, of course, engineers have to craft the parts — namely, those essential and enormous mirrors. Astronomers have developed two designs for them.

Arizona’s Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab has cast mirrors for many of the world’s largest telescopes, including the 6.5-meter MMT Observatory and the twin 8.4-meter monsters of the Large Binocular Telescope, both in Arizona.

Superfast sky survey

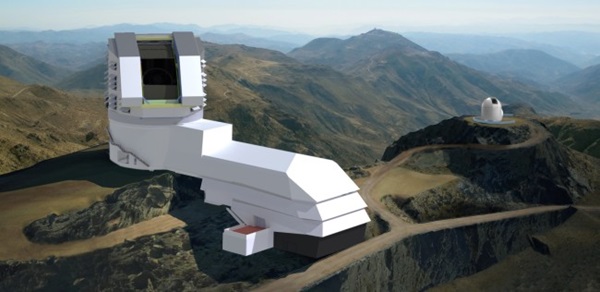

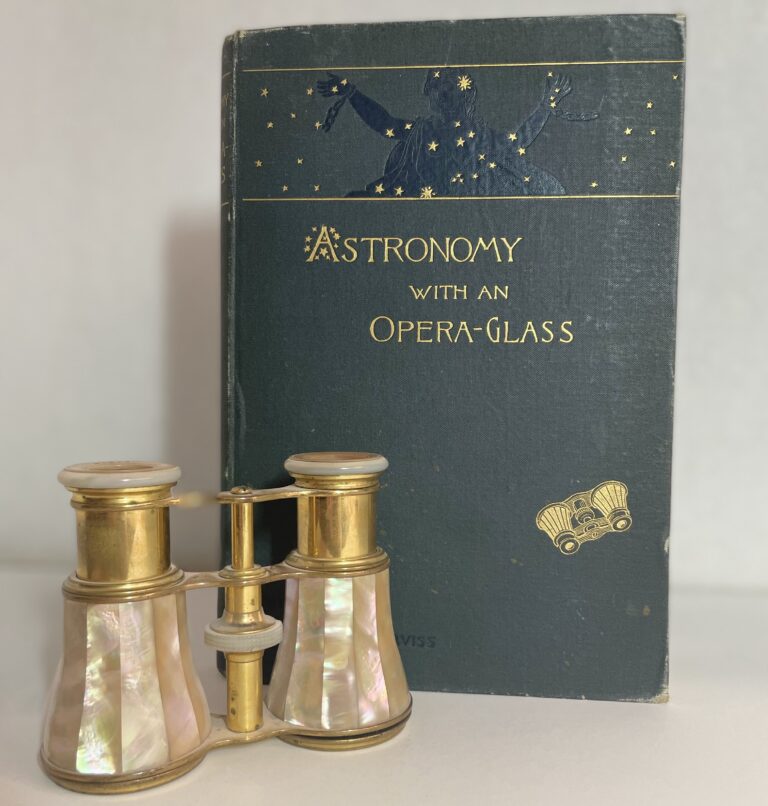

So what will these new instruments actually be, and what will they do? Of the four next-generation scopes preparing to revolutionize astronomy, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory should be the first to land on the scene. What sets the Rubin Observatory’s Simonyi Survey Telescope apart is not its size — its 8.4-meter primary mirror would fit in comfortably at several current mountaintop observatories — but its ability to image wide swaths of sky quickly.

Situated atop Cerro Pachón in north-central Chile, the Rubin Observatory should take just 15 seconds to deliver sharp images covering 9.6 square degrees of sky — equivalent to the area of more than 40 full Moons, and nearly 5,000 times the field of Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3.

Equally important to the Rubin Observatory’s success is its 3.2-gigapixel imaging camera. The largest digital camera in the world is not one you would want to lug along on your next vacation: It spans 5.5 by 9.8 feet and weighs about 6,200 pounds. With it, the Rubin Observatory will take two consecutive 15-second images of a single patch of sky, and then quickly compare them to reject any stray radiation hitting the detectors. (It’s similar to taking multiple photos of a famous building to digitally remove the tourists.) The scope then whips to the next area of sky — a movement that takes just 10 seconds, on average — and repeats the process. Such rapid-fire imaging means the Rubin Observatory can cover the entire sky visible from Cerro Pachón every three days.

This will be a boon to scientists studying transient events, such as the stellar explosions that produce novas and supernovas. The Rubin Observatory’s efforts should also develop a detailed census of small solar system objects, discovering 10 to 100 times more near-Earth objects and distant Kuiper Belt objects beyond Neptune’s orbit.

The Simonyi Survey Telescope’s mirror, cast in the Caris Mirror Lab starting in March 2008, made it to the mountaintop May 11, 2019. Astronomers expect it to come online in 2021, with full science operations for its planned 10-year survey starting in 2022 after it’s fully calibrated.

Seven times the charm

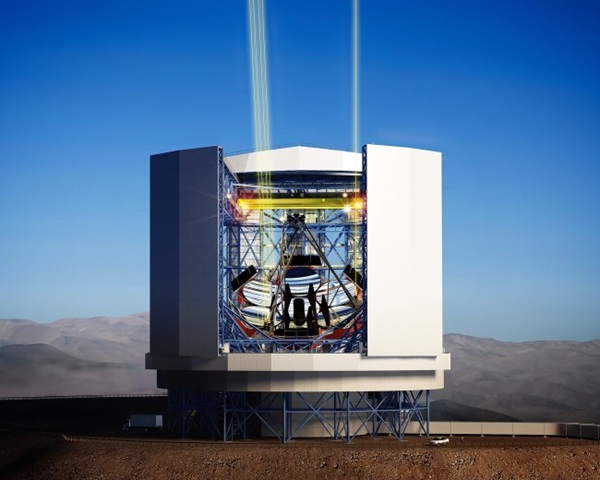

If one huge mirror can deliver so much science, why not try seven? That’s the idea behind the GMT, under construction at Chile’s Las Campanas Observatory. The GMT comprises seven 8.4-meter mirrors in a single structure, arranged in a daisylike pattern with one central mirror surrounded by six “petals.” The Caris Mirror Lab has been busy working on this project, and just completed the second mirror in July; the next three have all been cast and are at various stages of grinding, polishing or testing. At Las Campanas, a 40-person crew finished excavating the telescope’s foundation last spring.

A hex upon Your scope

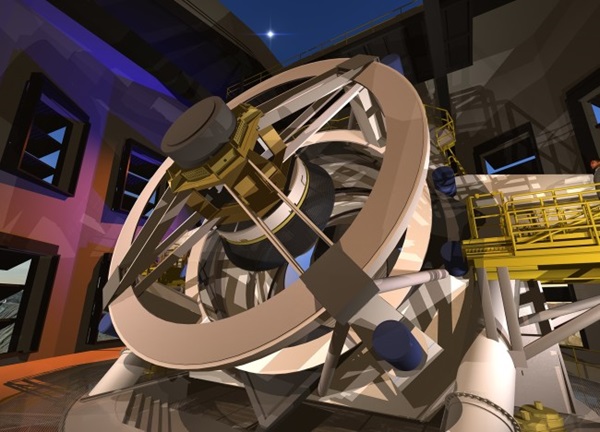

The other two giant telescopes of the next decade have gone a different route. Both the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) will consist of hundreds of hexagonal segments joined together to create mammoth collecting areas.

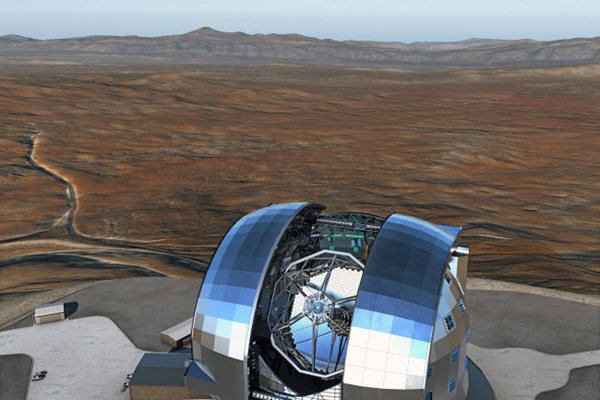

Europe’s ELT boasts 798 segments in its primary mirror — each measuring 55 inches across — giving the telescope’s primary mirror an aperture of 39 meters. The German optical company Schott cast the first of these segments in early 2018, and has been churning them out since. Groundbreaking for the mammoth telescope took place in June 2014 on Cerro Armazones, a 9,993-foot mountain in Chile. If all goes according to plan, the ELT should see first light in 2025, around the same time as the GMT.

But the site also comes with a major drawback. Mauna Kea is sacred to Native Hawaiians, and the telescope’s construction has drawn various protests. It wasn’t clear whether the new observatory would ever be built, but Hawaii’s Supreme Court ruled in October 2018 that construction could proceed.

The TMT’s enclosure — which will house the scope itself and related electronics — is already finished and awaiting shipment to the island from Canada. With the legal challenges presumably settled, scientists are looking toward first light in 2026.

Science by the boatload

With their unprecedented light-gathering power and resolution, the GMT, ELT and TMT promise astronomers the best views yet of faint objects and crowded regions. Scientists expect these behemoths to shed light on a variety of vexing problems. Close to home, hunting for Earth-like planets in Earth-like orbits around nearby stars will be a priority. Even more exciting will be the new ability to scrutinize these worlds. “Most of these exoplanets are in too close to their parent stars to study today,” says McCarthy. But with the GMT and other large scopes, “We’ll separate the light of hundreds of planets from their host stars. We’ll be able to track weather through color changes and look at the chemistry of planetary atmospheres.”

These giant telescopes should also answer even bigger questions about the basic structure of the universe. With these large-aperture scopes and infrared capabilities, McCarthy says, “we’ll [be able to] look back to the early universe, to galaxies only 100 to 500 million years old.” This will be a vital first link to providing a grand view of how galaxies evolve over time, and their relation to the supermassive black holes at their centers. The scopes should even illuminate how the Milky Way has grown by swallowing nearby dwarf companions, and potentially solve the riddle of what came first: galaxies or their black holes.

On the biggest stage, the cosmos still baffles scientists seeking explanations of the dark matter that holds galaxies together and the dark energy that causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate. These new telescopes will provide vital new data to help solve these mysteries, and may help resolve the discrepancy between different ways of measuring the universe’s expansion rate.

In most of these endeavors, the big new scopes will work together with the orbiting 6.5-meter James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2021. With any luck, we may know a lot more about the intricacies of our cosmos in the next 10 to 15 years. But as the Hooker and Hale telescopes showed, we may also have a new batch of mysteries to try to figure out.

Editor’s Note 12/7/2020: Following its renaming after the original text of this story was published, references to the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) have been updated to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the Simonyi Survey Telescope.