Key Takeaways:

The comet NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) was first discovered on March 27, 2020, before becoming very bright, visible in July to the naked eye by Northern hemisphere observers. While we have long since become accustomed to the passage of comets and other celestial objects, that was not the case in 1910, when Halley’s comet made its first predicted return since 1834. In 1910 Halley’s comet first becoming visible to the naked eye on April 15, remained so until July 5.

Because the true nature of comets was just beginning to be understood, the comet’s passage caused great concern in Europe and the United States. Some even feared that the comet could cause illness or death, and might even be capable of bringing about the “end of the world”. As with the period in which we live now, with unscrupulous individuals hawking “miracle solutions” against Covid-19, including herbal teas, colloidal silver, and even a “stopgate” toothpaste – the gullible had an endless variety of pseudo-scientific products to choose from.

The fear of Halley’s comet stemmed from two facts. First, its closest approach in 1910 was 23 million kilometres from the Earth, just 60 times the distance to the Moon. The comet’s tail even crossed the Earth’s trajectory on the night of May 18-19. Second, a toxic gas, cyanogen, had just been detected in the tail of the comet Morehouse. In short, Halley’s comet was perceived by many as a huge ball of toxic gas approaching Earth at an astronomical speed of 190,000 km per hour.

The experts take the floor…

Faced with mounting fear, French authorities asked Camille Flammarion, a trustworthy and popular astronomer, to speak to the public. Flammarion considered the possibility that life on Earth might be extinguished should there be a celestial collision with Halley’s comet. Should a sufficient quantity of hydrogen in the comet’s tail be combined with atmospheric oxygen, all animal life could suffocate in just a few moments.

Flammarion considers the event unlikely due to the scarcity of gas in comet tails – a fact that would be confirmed later – but he admits uncertainty.

“We can admit that we ignore what fate has in store for next May. […] The human race would perish in a paroxysm of universal joy, delirium and madness, probably very enchanted with its fate.”

Flammarion, as a respectable scientist, recounts all the known elements in his possession: the facts, arguments, and causes, all accompanied by probability. However, the press echoed the most extraordinary part of his words – the possible suffocation of all of humanity – and passed over its low probability and its supposedly hilarious effect. Thus “informed”, the general public became understandably terrified of the potentially lethal effects of the comet’s passage.

When the comet approached in February of that year, spectroscopic observations at the Yerkes observatory in the United States confirmed the presence of cyanogen in the tail. Scientists detailed what would happen if the Earth’s orbit and the tail’s orbit cross paths: the cyanogen will decompose in the upper atmosphere, eliminating any danger of suffocation. Yet their reassuring conclusions went largely unnoticed by the press and the general public.

Panics and feasts

Following the dissemination of the information of an imminent danger, the reactions were diverse. Some people began to sell all their worldly possessions to take advantage of the short time remaining. Others risked death by alcohol overdose rather than gas intoxication. Others in the United States caulked their windows in a fruitless attempt to prevent the poisonous gas from entering their homes. In France and Italy, others took refuge in churches, the doors of which remained open during that famous night in May 1910. Several tens of thousands of believers gathered to pray in St. Peter’s Square. A Hungarian preferred to commit suicide rather than risk being suffocated.

In this context, charlatans seized the opportunity to sell anti-comet pills, based on sugar and quinine, and even an anti-Halley’s comet elixir

Of course, not everyone panicked: Flammarion and other astronomers were invited by Gustave Eiffel to the eponymous tower to observe the comet, and many Parisians took the opportunity to feast and dance all night. To the surprise of some and the disappointment of others, only a small and faint nucleus was visible, if it was visible at all – as we now know, Halley’s comet is rarely bright when it passes.

During the comet’s passage, the Air Liquide company took samples of the atmosphere in Paris and found no trace of toxic gas. And the irony is that after-the-fact calculations determined that the comet’s tail did not cross our planet’s path in 1910. In fact, it missed us by at least 400,000 km, roughly the distance from the Earth to the Moon. The error occurred because the comet’s passage was predicted by only simple geometric considerations and moreover, its gaseous tail had a pronounced curve.

Comets, ominous birds for a millennium

A few months earlier, in January 1910, a large comet named C/1910 A1 appeared in the sky, first seen dimly in South Africa and then brightly in Europe. Initially confused with Halley’s comet, it had been nicknamed “the Great Comet”. We can easily understand why these “dazzling stars with long flowing hair” have always fascinated, especially since the absence of light pollution at the time allowed everyone to see them.

To better understand how impressive comets once were to us, remember the 1066 representation of a comet – it was Halley, even if it does not yet bear that name – on the embroidery of Queen Mathilde, better known as the Bayeux tapestry. The comet appears at the top, next to the Latin text “Isti mirant stella” (“they admire the star”). A crowd points towards the comet, which looks more like a sunflower pulling a rake behind it, the tail of the comet being – already – more frightening than its head.

The superstition at the time generally associates the appearance of a comet with the omen of a catastrophe. The comet crossed the sky of Europe in April of that year and the Battle of Hastings would not take place until mid-October. While King Harold of England saw in the passage of the comet as an omen of invasion, William the Conqueror was confident that it predicted success in his planned conquest. In the hair of the comet some even saw a resemblance to the crown of England. But if William had lost the battle, wouldn’t certain texts have reversed the prediction after the fact? In heaven as on Earth, one man’s loss is another man’s gain.

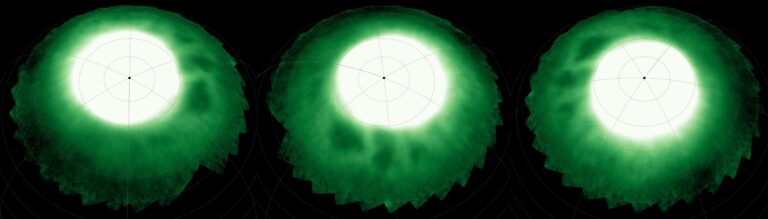

Today, comets are much less fearful, as the new comet NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) proved. For most of us on Earth it went unnoticed, lost in the gleams of nocturnal lightings of civilisation, and failed to break into the news cycle. Yet if this had happened a thousand years ago, it is easy to imagine that our new celestial companion could have been seen as omen of the current pandemic.

![]()

Sylvain Chaty, Professeur des Universités, astrophysicien au CEA, Université de Paris

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.