While most Western space enthusiasts remember the American Skylab space station, only some recall the long series of Soviet orbiting labs called the Salyut space stations. The last of these, Salyut 7, famously “died” in 1985, when a loss of power shut down all of its systems. But later that year, two cosmonauts risked their lives to revive the radio silent space station.

Salyut, variously translated as “salute” or “firework,” was a Soviet program that ran from 1971 to 1986 and included the world’s first space station, Salyut 1. The Salyut space stations had both military and civilian applications, but they were largely designed to pioneer the technology required to build modular space habitats.

A cascading electrical failure

In February 1985, after hosting three cosmonaut crews (including one that stayed for 237 days, a record at the time), the vacant Salyut 7 space station started to experience trouble. Workers in the TsUP (the Soviet version of NASA’s Mission Control) noted that an overcurrent had tripped a circuit breaker, which shut down the station’s primary long-range radio transmitter.

Ground controllers switched Salyut 7 to its backup transmitter, which seemed to solve the problem — at least for a bit. However, a subsequent attempt to restart the primary transmitter created another overcurrent that started a cascading series of electrical failures. Both radio transmitters (primary and backup), as well as the station’s radio receivers, ceased to work.

Attempts to revive the station from the ground failed. Salyut 7 went silent. It began to slowly tumble.

Making matters worse, the interior of the station rapidly lost heat, eventually reaching a frigid, yet stable, temperature of about –4 degrees Fahrenheit (–20 degrees Celsius). Soviet engineers realized they had only two options: abandon Salyut 7 or mount a rescue mission.

At this point, the Soviet’s larger, more advanced Mir space station was still a work progress. Waiting for Mir to launch would have meant putting all spaceborne work on hold for at least a full year. So, although a crewed rescue mission to Salyut 7 was a dangerous proposition, if successful, the Soviet’s would save both time and money — as well as face.

A space rescue begins

The Soviets understood that docking a crewed Soyuz spacecraft with Salyut 7 was a supremely dangerous maneuver. A failed docking could cripple the Soyuz, stranding the crew in orbit, if not killing them outright.

Soviet spacecraft usually depended on an automated docking system, but that relied on computers aboard both vessels being in constant communication with each other. But, in essence, the Soyuz’s dance partner was giving it the cold shoulder. Fortunately, cosmonaut Vladimir Dzhanibekov had previously performed a manual docking with the (then-functioning) Salyut 7, which was partly why he was chosen to head the rescue mission; cosmonaut Viktor Savinykh would accompany him.

Dzhanibekov and Savinykh trained extensively on new protocols developed for the planned docking with the lifeless Salyut 7. And on June 6, 1985, the pair launched aboard Soyuz T-13.

During a long, slow approach to the station, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh noticed that Salyut’s solar arrays were no longer aligned with each other or the Sun, further confirming the severity of the damage. Fortunately, the station’s rotation rate was manageable. And by using an optical rangefinder, Dzhanibekov manually nestled the Soyuz near Salyut 7, linking the two craft at the forward docking port. “There is a docking!” he triumphantly called out.

Firmly attached to Salyut 7, the cosmonauts’ next task was to see if the station could be revived. If they couldn’t resurrect Salyut 7 and its systems, they would have no choice but to humbly return to Earth.

Saving Salyut 7

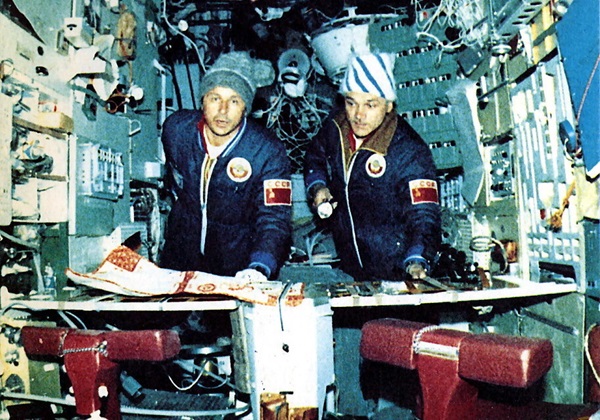

By methodically moving through a series of hatches, paying careful attention to equalize the pressures at each step, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh finally reached the work area of Salyut 7. Due to the sub-zero temperature, the two cosmonauts donned wool hats and heavy winter coats. Dzhanibekov described the environment as “kolotoon,” which is a slang term in Russian meaning extreme cold with harsh undertones.

The station was dark. All of its water supplies had frozen. The instruments and walls were covered with a fine layer of frozen moisture — a picturesque scene that belied the severe risk of an electrical short. The cosmonauts performed an analysis of the air quality aboard the station, confirming it was breathable, and opened the porthole shades to allow sunlight to help warm the station.

Although Salyut 7 had no power, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh did find some operable batteries onboard. They connected them to the solar panels, and by using the Soyuz’s thrusters, they moved the entire station to properly align it with the Sun.

Once the batteries charged up, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh began to bring Salyut 7’s vital systems back online. One at a time, they revived the lights, communications, water storage and delivery apparatus, and so on. Working tirelessly, and under the harshest of harsh conditions, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh astonishingly resuscitated all of Salyut 7 in just 10 days.

The legacy of Salyut 7

With the station back up and running, the crew of Soyuz T-13 was no longer on a rescue mission. It was time for them to settle in. Dzhanibekov remained in orbit for 110 days, while Savinykh spent 168 days on the station (they returned home aboard different, subsequently launched, Soyuz flights). The rescue of Salyut 7 would serve as Dzhanibekov’s final space mission, though Savinykh would fly in space several more times.

Salyut 7 was the last of the Salyut stations, remaining in space for six years after initially going dark. But as its orbit decayed, accelerated by solar activity, Salyut 7 eventually burned up over South America on February 7, 1991.

The rescue of Salyut 7 has sometimes been compared to the ill-fated flight of Apollo 13: both missions involved dead and freezing spacecraft that put human lives at risk, and both missions succeeded thanks to extensive coordination between astronauts/cosmonauts and ground controllers.

Dzhanibekov and Savinykh, however, had the advantage of a fully functioning Soyuz spacecraft, which could ferry them back them Earth at any time. Plus, the cosmonauts were working in Earth orbit, while Apollo 13 astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise were fighting to get home from the depths of cislunar space.

Still, both missions showcase the incredible fortitude humans are capable of — even while under extreme duress — when they have the proper support, guidance, and determination to succeed.

Doug Adler is the co-author of From The Earth to the Moon: The Miniseries Companion