Key Takeaways:

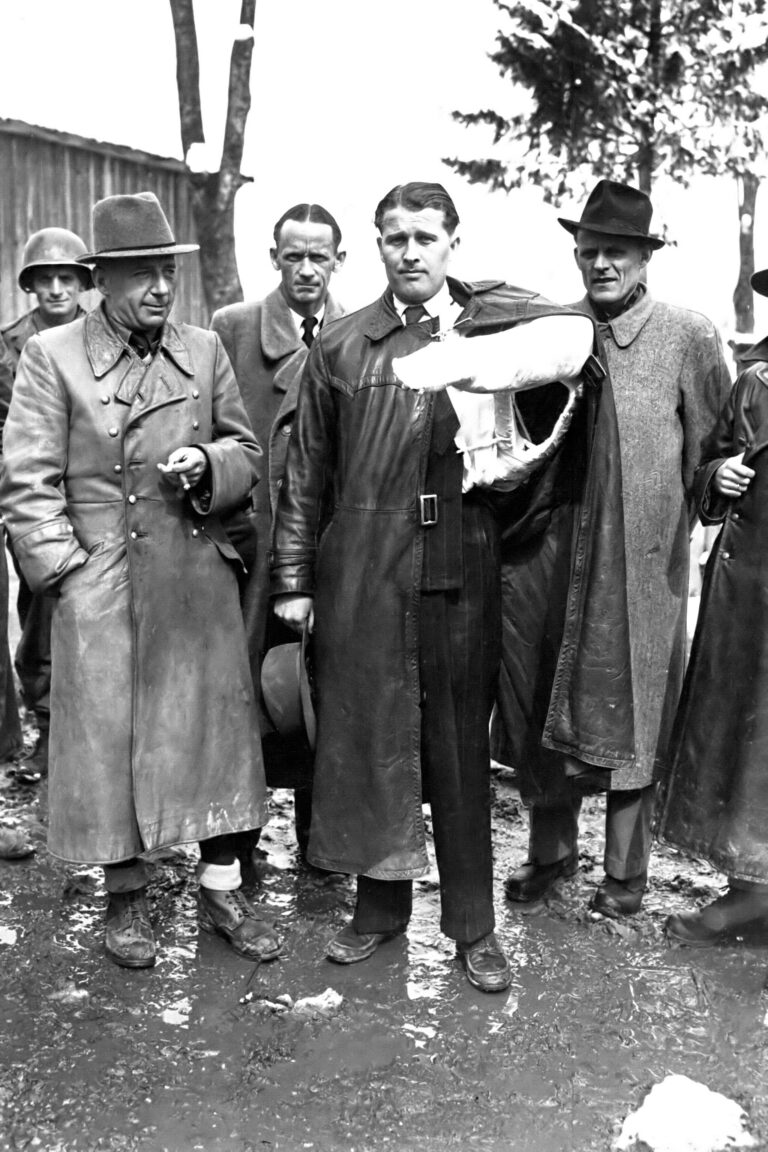

Early on November 2, 2000, two Russian cosmonauts — along with an American astronaut who once boasted he could kill a man with a knife — squeezed through a narrow hatch orbiting some 250 miles (400 kilometers) above Earth’s surface. It took two days flying aboard a Soyuz spacecraft for former Navy SEAL Bill Shepherd, fighter pilot Yuri Gidzenko, and engineer Sergei Krikalev to reach their destination. But when they finally flicked on the lights of the International Space Station, they cemented themselves as the orbiting lab’s first full-time crew.

As the members of Expedition 1 clasped hands in brotherly solidarity, they heralded the dawn of 20 years — and counting — of humanity’s continuous presence in space.

A quick look at the ISS

The International Space Station (ISS) is one of the grandest engineering endeavours of all time. Nobel Prize nominee, official U.S. National Lab, and humanity’s brightest man-made star, the station is readily visible to the naked eye as it tracks across the night sky. But unlike any other satellites you may spot above, the ISS has hosted 242 people from no less than 19 sovereign nations since its construction began in December 1998.

The station’s past residents include the first astronauts from South Africa, Brazil, Sweden, Iran, Malaysia, South Korea, Denmark, and the United Arab Emirates. But the ISS has also hosted the world’s oldest spacewalker, the oldest woman in space, and the first pair of spacewalking grandfathers. It’s even served as the site for the first space marriage, as well as the first space marathon.

Building, restocking, and crewing this colossal edifice in the sky has so far taken 37 Space Shuttle missions, 63 Soyuz flights, and even a recent trip on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. In addition, 73 Russian Progress freighters, 34 commercial Dragon and Cygnus cargo ships, nine Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicles (HTVs), and five European Automated Transfer Vehicles (ATVs) have delivered essentials such as food, water, clothes, experiments, fuel, tools, and spare parts.

However, these resupply missions aren’t only about restocking necessities. Their cargo has also contained birthday cards, holiday gifts, specific toothpaste, a 3D printer, and even an espresso machine. Recently, a Cygnus cargo ship dropped off a new toilet (which, admittedly, is a necessity), along with Estée Lauder skincare products for an in-space advertising campaign.

The past 20 years

Since the initial arrival of Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev to the space station, 63 additional expedition crews have lived and worked on the ISS for periods lasting from a few months to more than a year.

In the early days, rotating crews of three were dropped off and picked up by space shuttles. But because the shuttles didn’t usually linger for long, the crew needed an emergency escape option. Russia sent up regular Soyuz ‘taxi’ flights, whose crews spent a few days working with the expedition crew, dropped off a fresh ship, then returned home in the old one.

Those taxi flights permitted, for the first time, fare-paying visitors. In April 2001, engineer Dennis Tito paid $20 million to become the first commercial ‘spaceflight participant,’ spending a week aboard the ISS. His flight, however, would not be the last.

Then, when NASA retired the Space Shuttle Program in 2011, all three seats on each Soyuz flight were again reserved for expedition crews. Opportunities for paying astronauts dried up.

A decade later, however, with the arrival of commercial Crew Dragon and Starliner ships, space tourism looks set for a renaissance. The Houston-based firm AxiomSpace recently announced plans to fly former astronaut Mike Lopez-Alegria and three tourists — including actor Tom Cruise and producer Doug Liman — aboard a Crew Dragon mission to the ISS next October, where they’ll potentially work on a movie filmed in space. Meanwhile, Russia intends to send two tourists to the ISS, along with a professional cosmonaut, aboard a Soyuz flight in December 2021.

The next 20 years?

Such commercial flights must have been beyond the wildest dreams of Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev when they first boarded the infant station two decades ago. For them, the ISS was, and remains, a cutting-edge orbital lab. To date, it has supported more than 2,700 research investigations from 103 countries, ranging from subjects like life and material sciences to fundamental physics and experimental technology.

In its early days, the station’s full-time crews mainly consisted of Americans and Russians. But since 2006, other ISS partner nations have played an increasing important role. Astronauts from France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Canada, Japan, Italy, and Germany have all taken turns commanding the station.

Over the past two decades, multiple historic achievements have been carried out on (or just outside) the ISS — including the first national spacewalks for Canada, Sweden, Italy, as well as the first all-female spacewalk performed last year by NASA astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir.

Just 20 years after Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev first entered the ISS, the space station has time and again proven itself to be one of humanity’s greatest achievements. But perhaps the most important legacy of this human foothold to the heavens is that it has drawn a multitude of nations together in pursuit of peaceful goals — goals based on both impartial science and international cooperation.