Now, NASA’s Juno spacecraft appears to have captured these flashes in the stormy clouds of Jupiter — marking the first time these events have been observed on another planet. The new research was published October 27 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

Atmospheric sprites and elves

Both sprites (which stands for — get ready for it —Stratospheric/mesospheric Perturbations Resulting from Intense Thunderstorm Electrification) and elves (Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources) are a type of transient luminous event, or TLE. These strange phenomena, which only last milliseconds, are occasionally seen above thunderstorms.

And although sprites may be visible with sharp, dark-adapted eyes, both phenomena are more often caught on film. Sprites were serendipitously captured by a camera for the first time in 1989, but the existence of elves wasn’t confirmed until orbiting space shuttles recorded them on video in the 1990s.

Sprites typically have a round, blobby center that sprouts tendrils of light reaching upward or downward. They can look like anything from trees and jellyfish to the fairy tale creatures for which they’re named. Sprites occur when lightning bolts funnel positive charge from cloud to ground, leaving the cloud negatively charged. This, in turn, triggers activity in the atmosphere above the storm: a sprite.

Unlike lightning, which heats the air to incredible temperatures, sprites aren’t hot. They’re actually a cold plasma (think fluorescent light), not a bolt of electricity. They originate at altitudes around 40 miles (65 kilometers) high, but their wispy filaments can reach down as low as 20 miles (30 km) above the ground.

Elves, on the other hand, look more like expanding doughnuts or rings. They occur higher than sprites, around 62 miles (100 km) above the ground, reaching diameters up to 300 miles (480 km) wide. But even though elves are often spotted alongside sprites, the two aren’t caused by the same effect. Instead, elves form when electromagnetic pulses released during a thunderstorm slam into the ionosphere.

Juno spots otherworldly flashes

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has been in orbit around Jupiter since 2016, has provided researchers with a unique view of the gas giant’s stunningly turbulent atmosphere. That’s why scientists thought Juno would be the perfect tool to seek out TLEs, which they predicted Jupiter should have.

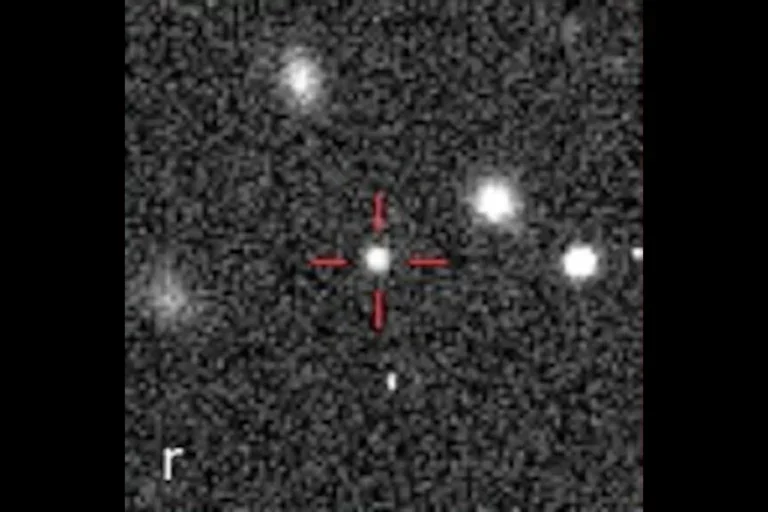

Juno’s Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) delivered. This instrument looks at ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths shorter than visible light, and over the course of the past four years, it has captured 11 brief, bright flashes of UV light lasting between 0.1 and 2.5 milliseconds. Not only are the 11 flashes the first-ever lightning-like flashes recorded on Jupiter at UV wavelengths, they also appear to be the first-ever TLEs spotted on another world.

Each of the flashes originated at altitudes around 186 miles (300 km). This region is above the water cloud layer in Jupiter’s atmosphere, where jovian lightning is generated, and is exactly where sprites and elves were assumed to form on Jupiter. The likely TLEs also showed the distinct signature of hydrogen emission, again matching predictions.

Adding to the evidence for extraterrestrial TLEs, researchers found that the 11 flashes occurred above areas in Jupiter’s atmosphere known for their roiling thunderstorms. Although no lightning strikes were observed immediately before the TLEs, the researchers say that’s not unexpected, due to the way Juno’s instruments were observing the area at the time. It’s likely that lightning flashes did occur, the researchers say. But the bolts were simply not recorded, thanks to the way different instruments on the spacecraft observe.

Researchers still aren’t sure which kind of TLEs Juno saw — whether sprites, elves, or a combination of the two. But they do think further Juno observations taken when the spacecraft is closer to Jupiter would help them differentiate between the two different breeds. Additionally, now that they know what to look for, the researchers think it will be easier to spot these phenomena on other planets, too. Ultimately, the goal is to use these stunning, otherworldly lights to untangle the complex behavior of planetary atmospheres throughout the solar system — including Earth’s.