Key Takeaways:

- Physicist Stephen Webb's extensive work addresses the Fermi Paradox, which questions the absence of observable extraterrestrial intelligence despite the universe's vastness, by compiling and analyzing numerous potential explanations for this phenomenon.

- A significant challenge in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) is the "modernity bias," where search methodologies are often constrained by human technological paradigms, potentially overlooking advanced or unconventional communication methods such as neutrinos, tachyons, or gravitational waves.

- The article critiques the statistical argument for widespread intelligent life, positing that the cumulative improbability of multiple necessary evolutionary transitions (e.g., abiogenesis, intelligence development, technology advancement) may render even a vast number of exoplanets insufficient, further challenging human-centric assumptions about evolution and civilization.

- Quantitative analyses, such as those incorporating probability distributions into the Drake equation, suggest a considerable likelihood (ranging from 39% to 99.6% depending on the scope) that humanity may be unique within the observable universe or the Milky Way galaxy.

“I grew up — I guess you’d say — in a science fictional world,” says Webb, a bald British man whose alternately arched and furrowed eyebrows can tell a story of excitement and confusion almost as well as words do.

During that same childhood period, he was immersing himself in actual science fiction, in addition to this nonfictional reality that was so cool it seemed fake. He devoured books by canonical authors like Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. In the universe-webs the writers spun, humans rocketed around and interacted with interplanetary species. That lens shaped his view of everything — and everyone — in space. He came of age, he says, with “that idea that the galaxy contains weird and wonderful life-forms that one day we would go out and meet.”

Webb held on to that idea tightly — until, that is, as a young man studying physics, he read an August 1984 article in the magazine Asimov’s Science Fiction, written by geologist and science fiction author Stephen L. Gillett. It was called simply “The Fermi Paradox,” and it proposed something Webb had never considered: If the universe is so big, it likely produced intelligent life on other planets. Some of those lives must have built spaceships. Even at relatively slow speeds, given enough time, they’d disperse across the galaxy, just as humans had across the globe. And if that’s the case, as physicist Enrico Fermi famously wondered, where is everybody? Why haven’t we met any extraterrestrials?

“It just hit me with the force of a sledgehammer that all these things that science fiction, and science as well, had told me to expect — that one day soon we would make contact with aliens, and that maybe we’d go out and have all these Star Trek adventures with them — maybe that was all wrong,” says Webb.

Just as Asimov had given, Asimov had taken away, and Webb found himself in a new and unfamiliar universe. The assault to his preconceptions needled him, but he liked challenges, and he took this one on. “I got into the habit of starting to collect solutions to the so-called Fermi paradox,” he says. In notebooks and desk drawers and, eventually, computer files, he amassed a set of explanations for where “everybody” might be. The pile of potentials became a book in 2002: If the Universe Is Teeming With Aliens … Where Is Everybody? 75 Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life. In it, Webb argues with himself, vacillating between his childhood vision of a populated universe and that metaphorical sledgehammer. Maybe SETI scientists have not found any extraterrestrials because none exist.

The modernity problem

“If you go outside and look up on a clear night, it’s almost impossible to believe that we are alone,” says Webb. In England, he doesn’t get many clear nights. But when he does, and he steps outside and sets his gaze skyward, he sees the same constellations dot-to-dotting that he did in the Apollo era. He still feels the pull of his childhood ideas. “There’s something innate in this feeling that we cannot be alone,” he says.

And that’s part of why he started collecting the Fermi solutions and setting them down in sentences. With a doctorate in theoretical particle physics from the University of Manchester, he was equipped to find, review, and evaluate the many ideas in his scientific realm. Having published eight science books with academic presses and having been invited to give a 2018 TED talk about his research, Webb is a well-recognized figure in the landscape of SETI. “I didn’t enter [the book] with a particular ax to grind,” he says. “And, in fact, I think I wrote it to kind of explore this in my own mind.” Webb’s book — and the pile of papers before that — explores dozens of Fermi solutions, under section headers like “They Are (or Were) Here” and “They Exist, but We Have Yet to See or Hear From Them.”

Many of Webb’s collected hypotheses suggest that aliens live where we’re not looking, talk how we’re not listening or resemble something we haven’t sought out. Maybe the aliens like to send messages or signals using neutrinos, nearly massless and barely-there particles that don’t interact with normal matter much, or tachyons, hypothetical particles that fly faster than light. Maybe they use the more-conventional radio or optical transmissions but at frequencies, or in a form, astronomers haven’t sought out. Maybe a signal is sitting on data servers already, escaping notice. Maybe the extraterrestrials subtly alter the emissions of their stable stars, or the blip-blip-blip pulsations of variable stars. Maybe they put something big — a megamall, a disk of dust — in front of their sun to block some of its light, in a kind of anti-beacon. Maybe their skies are cloudy, and they consequently don’t care about astronomy or space exploration. Or — hear Webb out — perhaps they drive UFOs, meaning they are here but not in a form that scientists typically recognize, investigate, and take seriously.

In 2015, Webb published a second edition of the book, because in the intervening years, others had postulated even more ways of seeing a signal. His favorites involve phenomena astronomers have studied closely only in the past decade or so. Maybe aliens could “spin up” millisecond pulsars — dead stars as dense as atomic nuclei that spin hundreds of times per second — giving them an energy bump like Hot Wheels cars passing over booster tracks. Or perhaps the cosmic cousins prefer to communicate using gravitational waves, the ripples in spacetime that earthlings just learned how to detect in 2015.

The aliens, should they exist, might be using technology humans won’t invent for millennia, if at all. And while scientists do sometimes see past Earth’s technological thresholds, they (and the rest of us) are notoriously bad at imagining where our own technology is going (did anyone predict Uber would come out of ARPANET?). How, then, could it be possible to imagine where alien technology might go?

Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan, who studies SETI scientists’ culture at Memorial University in Newfoundland, thinks modernity bias might be keeping scientists from seeing an alien fingerprint right in front of them. “It might look like nature or magic, or any number of things,” he says. “It might look like the background processes of the universe. It might look like physics.”

Maybe we’re alone

Webb thinks that maybe there is no right thing. It’s an idea he lays out in the book’s most interesting section, with the scariest subtitle: “They Don’t Exist.” There is no “everybody.” “It is just us,” he says, almost trying the idea on. The notion, he says, can feel as cold as the universe itself.

As he gathered his 75 solutions, Webb kept flipping between that intuitive emotion and what he realized his forebrain truly thought. “We’re just a rare fluke,” he says, sounding resigned.

Astronomers often suggest that’s unlikely. There are so many exoplanets, possibly multiple trillions just in our galaxy, and there are 2 million to 8 million (depending on which biologist you ask) species on Earth inhabiting even the most hostile places — from the cooling tanks of nuclear reactors to super-salty lakes to the crushing depths of the way-down ocean. Given the size of the universe and the sprawl of potentially habitable real estate, sheer statistics mean life has to exist. At least, that’s the traditional line of thinking. “Ultimately, the argument they are putting forth is that there are, for the sake of argument, a trillion places that life could get going on, and that’s a big number,” Webb says.

There’s a problem with that logic, though: “We don’t know in this context whether a trillion is a big number or not,” he says. That depends on statistical calculations.

Here’s how the statistical calculations work: To get intelligent life, you need solar systems with home stars that aren’t too violent. Those systems have to have habitable planets. Those planets have to go from empty to alive somehow, in a process called abiogenesis. Once life arises, it has to stay alive. Then, it not only has to evolve into something smart, but the smart things also have to develop technology. No one knows how likely any of those things is. Each if-then represents a kind of turning point, a transition from one phase to another. “They don’t need to be hugely rare transitions, if there are many of them, for ‘a trillion’ to actually appear quite small,” says Webb.

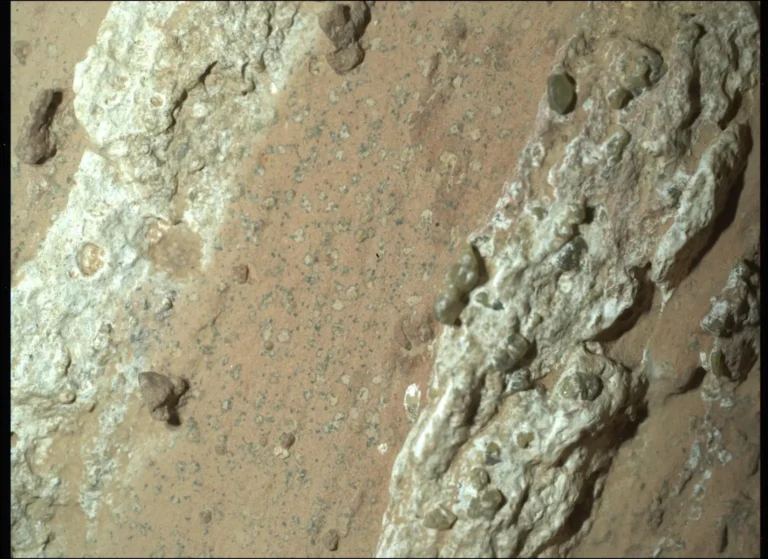

Many biologists, for instance, think abiogenesis is much more difficult than many astronomers think, and no one knows how it happened on Earth. While some scientists suspect that life inevitably progresses toward complication and intelligence, that’s a human-centric bias. “We don’t know if intelligence is a winning evolutionary strategy,” Webb points out. After all, some of the oldest species on Earth, including cyanobacteria (3.5 million years old), coelacanths (65 million years old) and crocodiles (55 million years old), are not smart by human standards. They definitely wouldn’t be able build a radio telescope or wonder if they were alone in the universe. Nevertheless, they persist, arguably better than we have.

Oman-Reagan’s research examines these kinds of assumptions, the ones scientists often bring without even realizing it. The conception of humans as the most intelligent and capable species on Earth? That might just be our ego talking. “The most advanced species on Earth might be the one that does the least harm, not the most,” he says. To that end, he believes SETI would do well to abandon the idea that technological civilizations are superior, the progressive and predictable result of evolution. While the scientists themselves might not necessarily put their thought process that way, the underlying idea is nevertheless that advanced technology will result from long-term evolution. These scientists recognize that not all “smart” beings may use technology like humans do, but the belief remains that life trends toward increasingly complex tool-use.

That’s part of the traditional definition of cultural evolution, a social-science term. But it’s “not clear at all” that when a civilization continues existing for a long time, it inevitably becomes ever more technological, says University of Texas anthropologist John Traphagan, who studies the relationship between culture, religion and science in SETI. There’s not necessarily a reason, then, to think that old aliens would be engineering wormholes or spooling up beacon-broadcasters.

Similarly, Traphagan takes issue with another SETI argument: The longer a technological civilization persists, the more likely it is to be nice, because it’s learned how to resolve conflict without apocalypse. “There’s no reason to think that altruism is going to be an outgrowth of technological superiority,” says Traphagan. “Predators are usually the ones that have the highest intelligence.” Besides, why would a planetary society be monolithic in any way — good or bad? Humans certainly are not. Astronomers’ ideas on this point don’t make sense to him.

If social scientists were in charge of the search, he says, it might progress in a different direction. Such scientists do get invited to SETI workshops and conferences, and to contribute chapters to scholarly books about the search. But these religion researchers, historians, anthropologists and communications experts occupy the fringes of the field.

Webb thinks that may not matter. Chances are, he believes, there are no civilizations to contact, and so perhaps our efforts to undo assumptions, confront biases, and expand our intellectual horizons don’t affect the end result: silence, emptiness.

Researchers at the University of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute recently quantified that feeling. To calculate how many intelligent, communicative civilizations may be in our galaxy, scientists usually use the so-called Drake equation. It’s a way of mathifying the evolutionary progression of a civilization from nothingness to life, first introduced in 1961 by astrophysicist Frank Drake, with each transition representing a term in an equation. The problem with these terms, though, is that we don’t know what number to assign them: The possibilities have a range of uncertainties. Computational neuroscientist Anders Sandberg and his colleagues at the institute wanted to include all of that doubt in their own Drake calculations, to shed some light on the dark, quiet universe. “It seemed to me that there is important information in the empty sky,” says Sandberg. Instead of assigning actual numbers to each term in the equation, they used the full range of numbers, for each term, that reasonable research suggests.

The probability distributions that resulted surprised even them: Humans, they found, are likely to be alone in the observable universe, a possibility between 39 and 85 percent. “It’s actually a fairly plausible thing,” says Sandberg. The team calculated that in the Milky Way galaxy, there’s between a 53 and 99.6 percent chance we’re alone.

That is, of course, just one group’s estimate. And “alone” doesn’t necessarily mean that there never was anybody. Maybe they were and just are not anymore, because of nuclear holocaust, irreversible climate change, epidemics run amok, asteroid impacts, nearby gamma-ray bursts, apocalypses we can’t imagine. Or maybe they never existed in the first place. Sandberg spins this possibility positively. If civilizations never existed, then the sky isn’t silent because they all destroyed themselves. “An empty sky doesn’t mean we are doomed,” says Sandberg.

Webb maintains a similar mindset. “I do have that basic optimism, which probably comes from science fiction,” he says, “that we will persist over centuries and millennia.” Perhaps even long enough to find out through SETI — which all of these naysayers actually believe we should continue — whether “everybody” includes anybody but us.