Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds is not your typical science documentary. There are no diagrams, no explanatory green-screens, no points where the narrator stops to define terms.

Of course, you wouldn’t expect that approach from Werner Herzog, the director of wild-eyed reveries like Fitzcarraldo and clear-eyed examinations of humanity’s relationship with nature like Grizzly Man. Neither does that style suit University of Cambridge volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer, Herzog’s co-director.

After Herzog featured Oppenheimer in his 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World, the pair collaborated on the film Into the Inferno — a meditation on volcanos, the people who study them, and humanity’s relationship with them. And now, the pair are back at it again with Fireball, taking that same anthropologic approach to meteorites and impact craters.

Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds is available on Apple TV+ starting November 13.

The duo of Oppenheimer and Herzog are not interested in making an “educational film” with Fireball, although you’ll surely learn something interesting from it. Their approach is to dive into how random encounters between space rocks and Earth have shaped human culture and history.

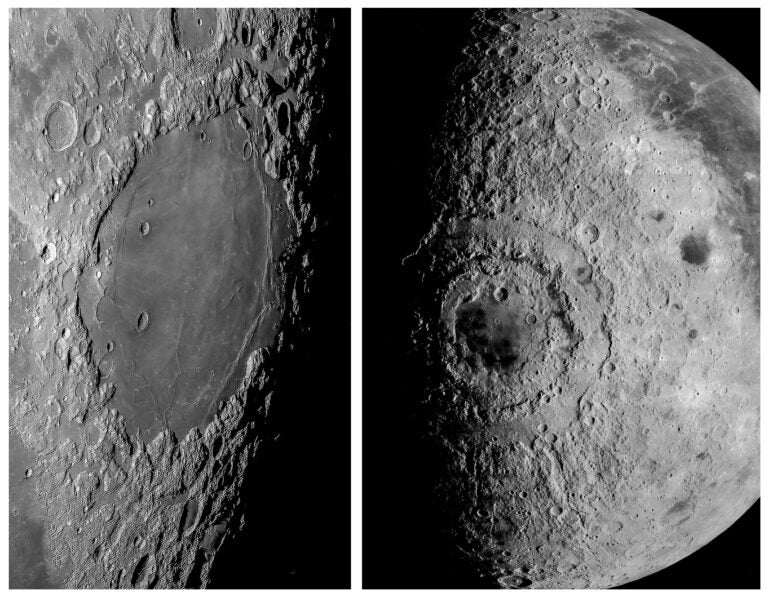

The film jumps between labs and locales all over the world, including: the ice fields of Antarctica, where researchers hunt for fallen stones on vast expanses of ice; the limestone sinkholes of the Yucatán Peninsula, where the Chicxulub impactor left its 93-mile-wide (150 kilometers) mark 65 million years ago; and Mer Island in the Torres Strait, where Melanesian Meriam elders recall myths that describe how meteors are a link to the afterlife.

Along the way, Herzog is the man behind the camera, while Oppenheimer doubles as an affable, curious host and expert. Researchers clearly view Oppenheimer as a peer, and his conversations with them are often unguarded, full of enthusiasm, and don’t shy away from technical details. In many ways, the film gets closer to the actual work of scientists and how they interact than any didactic, educational film ever could.

Recently, the pair hopped on a Zoom call with Astronomy to talk about the film. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Astronomy: Werner, I was recently rereading your 1999 Minnesota Declaration. And there were a couple of lines that jumped out at me, where you said, “The Moon is dull. Mother Nature doesn’t call, doesn’t speak to you … We ought to be grateful that the Universe out there knows no smile.” Now, you’ve made a film called Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds that is all about the ways in which Nature has appeared to speak to people through meteors. What is it about this topic of communicating with nature that intrigues you?

Werner Herzog: Well, I think nature is indifferent to what we are doing here. It is not interested in human beings. The universe couldn’t care less about our existence here on this little planet. And I do not like the Disney-ization of wild nature — that bears are fluffy creatures, and you better sing a song to them and hug them. I’m not a tree hugger. I’m not a bear hugger. And I do not want to hug the universe. It’s totally chaotic, totally violent out there, unfriendly out there. And it doesn’t smile at us, period. You don’t need to be a scientist to know that.

Astronomy: But there’s clearly something that fascinates you about people who are fascinated by nature, or perhaps think that there is something more to nature.

Herzog: Sure, of course, I’m fascinated by science and I’m fascinated by the awe of science. And, of course, my terrain is moviemaking, and moviemaking has a sense of awe — at least, in all of my films.

Clive Oppenheimer: What fascinates me is the cultural significance of these phenomena — the sight of shooting stars, the stones themselves that have fallen from heaven, and the impact craters. These are sites that become imbued with tremendous significance by human cultures throughout time and around the world. And that’s what really intrigues me and fascinates me about many geophysical phenomena — volcanoes, obviously, included — that there’s much more to them than their nature and their scientific aspects. It’s what they mean to us.

Simon Schaffer, historian of science [at the University of Cambridge] is asked in the film, “Why are you so interested in meteorites as a historian?” He says, “It’s that they have meaning, that when they’ve hit the ground and have been found by humans, their journey is just beginning.”

Astronomy: I read that you got the idea for this film after visiting a lab in South Korea. What was the story there, and what made you compelled you to then bring the idea to Werner?

Oppenheimer: So I’ve been doing research on a volcano in North Korea, called Paektusan. And I was over in South Korea for a meeting of geologists about this volcano and I made a side trip to the Korean Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) in Incheon, because I’ve worked in Antarctica for many years. And they gave me a tour of the building, which included a stop at the meteorites laboratory.

And I was talking with the meteoriticist Changkun Park, who was explaining to me what they do. He explained that his team had already found 1,000 meteorites in Antarctica. And so I was, of course, immediately baffled: “Why do you need to keep going back to get more? You’ve already got so many!”

But also, I was just struck by the scientific veneration of the samples. They had a selection, on display, behind a glass window into an ultra-clean laboratory. And each stone was in its own cubicle with a nitrogen atmosphere to preserve them. It was a very aesthetically beautiful set of specimens — iron meteorites, stony-irons, stony meteorites.

And I just immediately realized that this was another geoscience topic, like volcanoes, that entangled the nature with the culture and with the human — what they mean to us, these stones that fall from the heavens. And it put me in mind of the Black Stone in the Kaaba and the Grand Mosque in Mecca — one of the holiest relics of Islam — which may well be extraterrestrial in its origin.

And so I got back from that trip, very excited about this idea. And I spent a couple of weeks putting together some ideas and put a 3–4 page pitch together, outlining the themes: the origins of life, our destiny, and heaven and the heavens. So, I then got in touch with Werner and explained what I had in mind and we took it from there.

Astronomy: My favorite scene in the film is the one that, Werner, you called “science at its best” — a clip of the KOPRI researcher Jong Ik Lee on the ice fields of Antarctica, falling on the ground and shrieking in ecstasy at finding a meteorite on the ground. How did you find that clip and why did it resonate with you?

Herzog: Well, it’s sheer ecstasy. It’s just the incredible joy of discovery. It’s very cinematic. And then something odd happens: Somebody in the background is entering the frame with his rear end first. [It’s the] wrong timing. No apparent motivation. It’s very odd. It has everything — the joy of filmmaking, the joy of science. And Clive saw this material from Lee. He actually had the video and Clive immediately understood, we need to have that for our film.

Oppenheimer: That’s right. Jong Ik Lee and his wife, Mi Jung Lee, are both leading Antarctic geoscientists in Korea. They were the ones who’d invited me to the institute in the first place three years ago. And he invited us to film, to join on a meteorite search up on the polar plateau near the Korean research base in Antarctica, Jang Bogo Station.

And Jong Ik — he’s someone that truly comes alive when they’re in the field, when they’re out there against the elements and looking for things and finding them. And so the wildness to his character hadn’t really struck me.

In the clip, his exuberance on display was so, so wonderful. I mean, Jong Ik is in floods of tears. And I totally understand that — as a geologist, if I found that, I would be in floods of tears, and I was almost in floods of tears just watching this video.

Astronomy: Then you actually did find a meteorite when you were shooting in Antarctica, which is also captured in the film.

Oppenheimer: That’s right. I was thrilled to find that — not only because I’ve never found a meteorite before and I am a geologist, but also because I knew that our cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger, was up in the helicopter with the cameras rolling. So I was quite hopeful and confident that we would get some wonderful footage of it.

There was also a huge thrill because our meteorite expert, Takashi Mikouchi, from University of Tokyo, recognized instantly that it was not an ordinary chondrite. Ninety-five percent of finds are so-called ordinary chondrites, stony meteorites. He recognized that this was something different. In the end, it turned out to be a ureilite — a very rare variety of meteorite — which we learned when it was analyzed back at KOPRI’s lab in South Korea. So that’s an additional thrill.

Astronomy: Werner, you’ve been known to sometimes modify facts in your documentaries to better capture what you call “the ecstatic truth.” Did you modify any facts for this film, and if not, were you tempted to?

Herzog: Not really. I think when you do a film of this nature, you just take facts as they are and you respond to it. And my response has always been a response of awe, and that’s a form of ecstasy where we almost step out of our own existence. That’s quintessentially cinema.

But you see, there’s nothing wrong with modifying facts, for digging into a much deeper truth. The French writer André Gide once famously said, “I modify facts to such a degree that they resemble truth more than reality.” It’s a very deep statement for me.

For me, the witness of all witnesses is Michelangelo, with his sculpture of the Pietá, Jesus taken from the cross. The body of Jesus is the body of a 33-year-old man. And his mother when you look at her is 17. So, I have to ask, did Michelangelo try to cheat us? Give us fake news? Lie to us? No, he emphasized the deeper truth of both persons. So that’s what I like to do. But not in this film. It depends on what you’re doing. It’s all in the context.

Astronomy: You mentioned fake news. In this era of alternative facts, where we are awash with misinformation, do you feel like maybe the world at this moment doesn’t have room for the ecstatic truth? That maybe people would just settle for the plain truth?

Herzog: No, we have to — let’s not get into the definition of truth. We’ll continue until we are blue in the face. Don’t complain about misinformation and fake news and things. It has existed as long as we have evidence in writing.

We know for example, inscriptions on pyramids speak of the glorious victory of the Pharaoh and we know now, because a treaty between Egypt and the Hittites exists, that it was an inconclusive battle. When the Roman Emperor Nero died, fake Neros popped up — quite a few of them, in Northern Greece, in Asia Minor. We had Potemkin villages where a nobleman close to Catherine the Great, to show that his province was thriving, built facades of beautiful villages, but they were only paper mâché facades where the tsarina drove through.

So, we have had it all the time, and there’s nothing particularly new about it. But we have to get smart in the era of the internet. We have to understand how the internet is functioning to sniff out the fake news. And you can do so very, very quickly.

Oppenheimer: My mum always said, “Believe none of what you read and only half of what you see.” That’s a useful precept, I think. And, you know, the best way to avoid it actually is to shut your ears to it. I’ve found that my life is better when I don’t switch on the radio every day, in the morning, lunchtime, afternoon to get the latest news bulletin. It doesn’t improve my life.

Herzog: I am interested in news and I’m interested in the world around me. And when something doesn’t sound right, I immediately try to corroborate the news. And that’s why it’s healthy to corroborate what you hear on Fox News or what you hear on CNN with, for example, Al Jazeera, of all places. All of a sudden you have a different perspective. Or Russian television. Or go on the internet and find out and read the full speech of a politician and then you will know.

Oppenheimer: But the challenge is, you’re not corroborating news. You’re comparing propaganda. This isn’t straightforward.

Herzog: Yes, but you can filter certain things. I’m for looking at various sources and using common sense. Just use your common sense. And you know, “Oh, this not only stinks like a lie against the wind, it is a lie.”

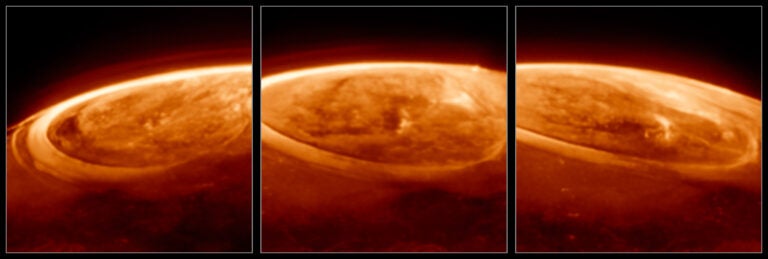

Astronomy: Speaking of news, I wanted to ask you about the recent news that perhaps there is phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus, and that it might be potentially a biosignature. Clive, what’s your take on that study as a volcanologist? Do you find that detection plausible?

Oppenheimer: So, the phosphine discovery is very, very interesting. A lot of my research has been trying to measure volcanic gases. And I do this spectroscopically, in somewhat similar ways to the way phosphine has been detected in the atmosphere of Venus.

The Venus spectroscopy, as far as I understand, is pretty robust. But it is possible to get spectroscopy wrong. If there are molecules that have unusual transitions that you haven’t really characterized, it’s possible to get things confused. [Editor note: Since the initial detection, several groups have called into question the interpretation of phosphine in the original data.]

But let’s say that the detection is sound. Of course, it still begs the question of whether there’s an inorganic pathway to producing phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus.

I think what’s interesting to me is that it’s not our natural reaction to think that, if we’re going to look for life somewhere on an exoplanet or elsewhere in the solar system, we’d look in the atmosphere — not in the soil, or the ground or the dust, or in the volcanic vents. I find that quite an intriguing idea.

Herzog: Clive, the exoplanets are way too far away for us to ever reach and see life and verify it. But Venus is close enough that we’ll know in a few years whether there are forms of life.

I do not expect green men coming from there. But it might be algae. It might — I keep jokingly saying — it might be life as intense as the snot coming out of the nose of a toddler, not superhuman creatures that want to destroy us. And it wouldn’t surprise me, because in meteorites we find building blocks of life: sugar, amino acids, you just name it.

And we should not forget that we have the same chemistry as the entire universe. We have the same physics as the entire universe. And we have the same history, which we share in the universe.

So it’s likely there is something out there. We have to expect it. But it doesn’t excite me very much. I think I’m content still being a Bavarian here and now, on this planet.

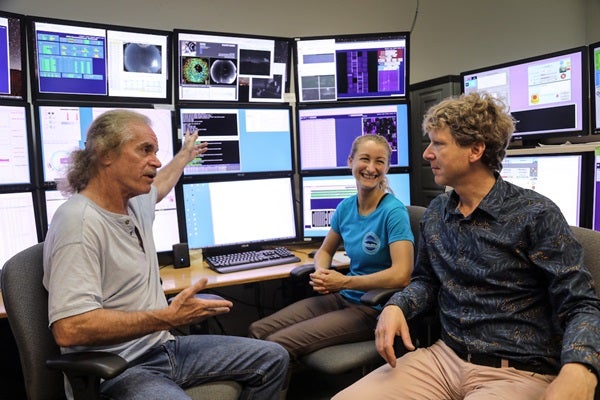

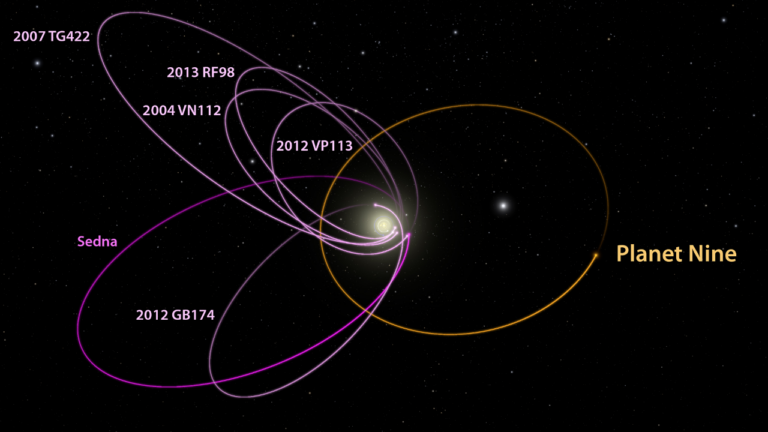

Astronomy: In the film, you go to Pan-STARRS on Mount Haleakala, which is a tremendous observatory in a fantastic location to observe the night sky. And you talk to the astronomers Mark Willman and Joanna Bulger, who are searching for potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroids, as they sit in the control room in front of their computers. What was it like to shoot that scene?

Oppenheimer: It was funny for me — I think it’s the only time I’ve been to a volcano and not actually looked at it.

You know, as we were about to head to Hawaii, there was a hurricane on one side and a tropical storm on the other side of Maui. So it really looked like we were gonna have an awful time there, and certainly not clear skies with the telescope. But we were very fortunate, actually, with a little opening in the clouds overnight, and they opened up the dome.

I love Werner’s line in the film where he says, in the control room, which is lower down on the slopes of Haleakala, “Just looking at their faces gave us a good amount of confidence,” referring to the fact that these two individuals are potentially going to turn out to be the most important people on the planet if there ever is a threatening bolide coming at us.

Herzog: Yeah. Well, when looking at the faces, it immediately struck me that they look like very sweet and very, very kind people. I would trust them. And I approached it as a filmmaker!

Of course, the scientific part of it is important. They are our guardians, our custodians. They are the nightwatch. And the entire army is sleeping — I mean, the entire world population is sleeping, and they keep watch. And if something is coming in, they will alert us.

Astronomy: Clive, I read that you chose the characters for this film — the researchers and the subjects. And it struck me as quite inclusive. It gives you a picture of science as it’s done by people all over the world, scientists who are women and people of color. And it also encompasses indigenous knowledge and traditions. Was that a conscious decision for both of you?

Herzog: I think so, yes. And I want to point out, I think even the slight majority of our witnesses — like Aboriginal painters, or scientists — are women.

And I love the fact that we have a citizen scientist in our film — the Norwegian jazz guitarist Jon Larsen, [who searches for micrometeorites by dragging a magnet through gutters in the parking lots of buildings with large slanted roofs, like sports arenas, where tiny grains of fallen space rock collect].

He is fascinated by micrometeorites, finds a new methodology — very primitive; I mean anyone, every school, kid could do it — and he finds micrometeorites. And when they are magnified 3,000 times, they look like fantastic sculptures, the most beautiful things you can ever lay your eyes upon.

And there’s deep science in it and deep mysteries in it. They are messengers from out there, and they are the oldest thing you can ever touch, barely visible on your fingertip, like a tiny speck of dust. And you know that this speck of dust is 4,500 million years old, from the origins of our solar system. So, it has this inclusion of characters and unexpected participants in it that makes a lot of life for the film.

Oppenheimer: [A diverse cast was] an imperative. It’s not always easy. I mean, if you’re filming elders, if you’re filming priests, often you’re going to encounter men. But the biggest imperative was the film, and for it to be authentic, and to have authentic voices. And so those were the guiding principles in identifying our cast — and also to cover the different themes, whether it’s archaeoastronomy, whether it’s indigenous knowledge, whether it’s the perspectives of the Catholic Church.

Astronomy: Last question. In the film, you make reference to a scene from the 1998 film Deep Impact — the climactic scene when the asteroid hits the Earth. And that scene is all about the choices people make in the face of the end of the world and how they choose to spend their last moments. So, if you knew there was an asteroid coming tomorrow, how would you spend your final moments?

Herzog: Oh, there’s a beautiful answer we have from the reformer, Martin Luther. He was famously asked, “What would you do if the world went under, if the world disappeared tomorrow? What would you do today?” And he answered, “I would plant an apple tree.”

Astronomy: And would you plant a tree? Or would you start a movie?

Herzog: No, I would start a movie. I would start the first shots of a movie and then let the planet go under.

Oppenheimer: I’d think about the music track to accompany it. And I would put it on my CD player and play it really loud.

Astronomy: What track would it be, do you think?

Oppenheimer: Well, I think it would depend whether it’s a stony-iron or an ordinary chondrite. It’d depend. I’d have to think about it. Something that says on the label, “Play loud or not at all.”

Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds is streaming on Apple TV+ starting Friday, November 13.