Key Takeaways:

- Galileo Galilei may have observed Neptune as early as 1613, but misidentified it as a star, lacking the evidence to confirm his observation as a planetary discovery.

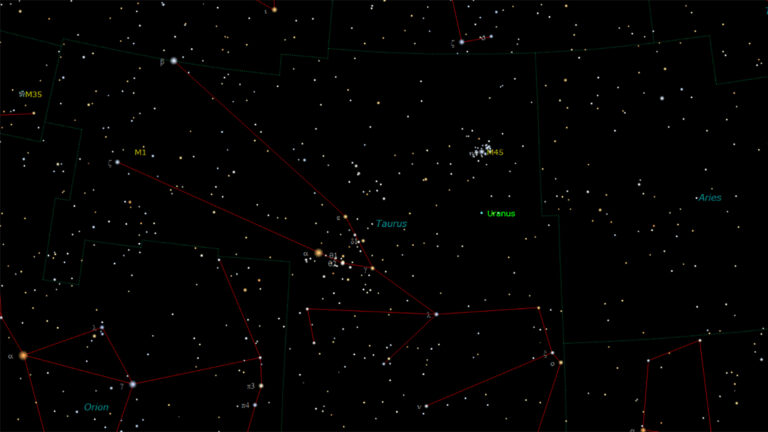

- Discrepancies in Uranus's orbit led to predictions of a trans-Uranian planet, independently calculated by John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier in the 1840s.

- While Adams completed his calculations first, Le Verrier's calculations were more precise and led to Johann Galle's observation of Neptune on September 23, 1846, based on Le Verrier's prediction.

- Despite initial joint credit to Adams and Le Verrier, subsequent historical analysis suggests that Le Verrier should receive primary credit for Neptune's discovery due to his accurate prediction and successful prompting of the search that led to the planet's confirmation.

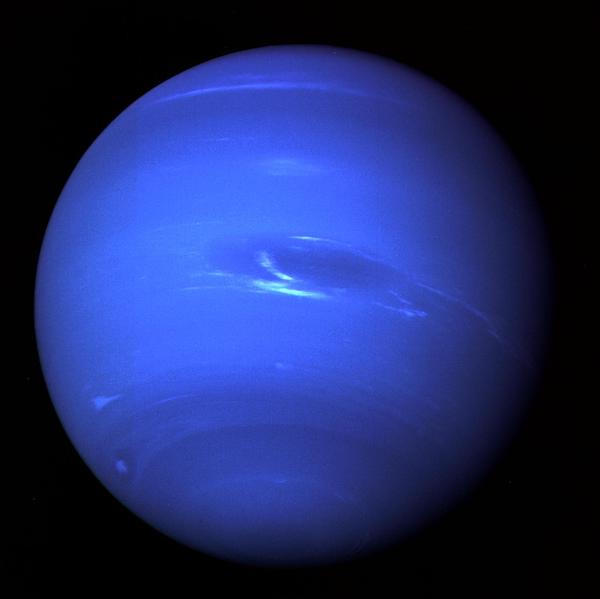

Between December 1612 and January 1613, Galileo Galilei sketched what he saw with his primitive telescope: a “point” near conjunction with Jupiter. Today, we know that “point” was exactly where Neptune was during those dates. It was just starting its retrograde — or backward — motion through the sky as seen from Earth. But Galileo seems to have mistook the planet for a star.

It took more than 20 years, however, before the young English astronomer and mathematician John Couch Adams started working on the problem. He had little confidence in his early results, which led him to keep starting over from scratch. But by early 1846, Adams had calculated new possible orbits for the predicted trans-Uranian planet. Still vacillating, though, he didn’t publish his work until November. Meanwhile, as Adams delayed releasing his results, French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier published his independent (and slightly different) calculations in June.

Meanwhile, after months of lukewarm responses from French astronomers, Le Verrier asked German astronomer Johann Galle to likewise hunt for the planet using Berlin Observatory’s telescope. Galle received Le Verrier’s letter on September 23, 1846. That same evening, Galle found Neptune. It was a mere 1 degree from Le Verrier’s predicted position, and 12 degrees from Adams’ prediction.

So, that raises the complicated question: Who really discovered Neptune? Adams? Le Verrier? Challis? Galle?

International controversy raged. Adams completed his calculations first, but Le Verrier published first. Le Verrier’s calculations were also more accurate. Challis did spot Neptune before Galle — twice. But out-of-date star maps and sloppy observing techniques meant he didn’t recognize it as a planet. International consensus eventually gave both Adams and Le Verrier joint credit.

And then, in 1999, a trove of long-lost (well, stolen) British documents came to light. They revealed a deliberate “bending of the facts” to make Adams’ role much stronger than it really was. While many sources still credit both men as the discoverers of Neptune, the historical evidence now says otherwise.

Credit for discovering Neptune must go to the person who predicted the planet’s location and convinced astronomers to search for it: Urbain Le Verrier.

But wait: In 2009 Australian physicist David Jamieson claimed Galileo did know he had spotted a planet, and that his notebooks prove it. In an entry on January 28, 1613 Galileo wrote that the “star” he saw appeared to have moved slightly relative to Jupiter. Jamieson also pointed to “a mysterious unlabeled black dot” in Galileo’s drawings for January 6. The black dot is in the correct position for Neptune. Jamieson hypothesized that Galileo added the dot to his earlier drawings “to record where he saw Neptune earlier, but had not previously attracted his attention….”

The problem is Galileo’s black dot from January 6 isn’t labeled. We know it was Neptune, but we cannot know what Galileo thought it was. And all the available evidence is that Galileo probably didn’t deduce the object’s true nature.

So, in other words, Neptune was officially discovered on September 23, 1846, by Urbain Le Verrier. Vive la France!