Key Takeaways:

As Earth circles the Sun, our planet regularly passes through dust and debris left in our path by passing comets and asteroids. Each time this happens, Earth experiences a meteor shower that fills the sky with bright streaks of light. These “falling stars” are the result of cosmic clouds of detritus burning up in our atmosphere. But does any debris from a meteor shower ever make it to the ground as a meteorite?

The answer is no. Meteor showers, despite their stunning light shows, don’t actually produce any meteorites.

Meteor vs. meteorite

Space rocks are called different things depending on their environment. When a piece of dust or rocky debris is floating out in space, it’s called a meteoroid.

A meteor, on the other hand, is the brief streak of light you see in the sky as a space rock slams into our atmosphere, generating friction that creates heat and light.

Finally, a meteorite is any part of a space rock that survives its dramatic fall to the ground.

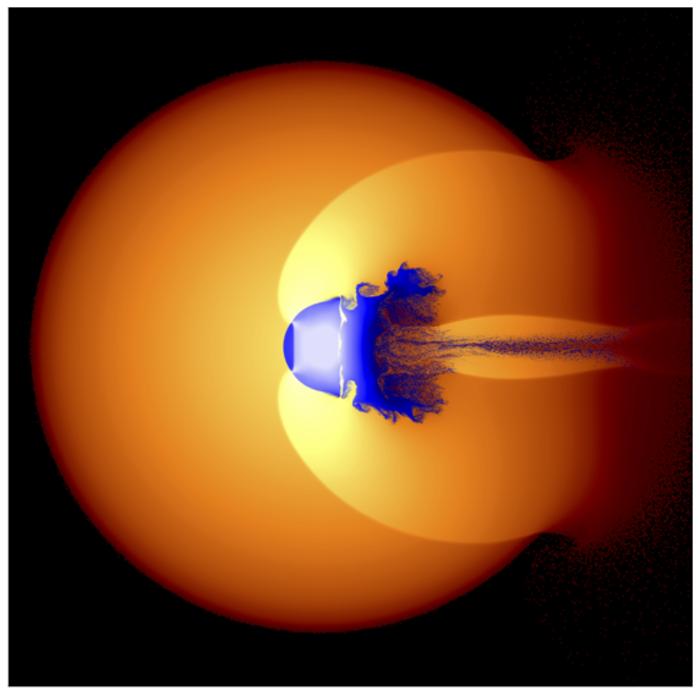

Most meteors occur high in Earth’s atmosphere, at altitudes between about 50 and 75 miles (80 and 120 kilometers). This layer of the atmosphere is called the mesosphere. (For spaceflight purposes, the Kármán line defines where our atmosphere ends and space begins. It’s located 62 miles [100 km] above sea level. However, the upper layers of our atmosphere actually stretch hundreds of miles above the ground.)

The faster a meteor streaks into the atmosphere, the sooner it will generate enough friction to light up. So, meteor showers made of faster-moving particles (those orbiting in a direction opposite Earth’s direction of motion around the Sun) appear higher in the sky than slower-moving ones.

But even when Earth isn’t flying through a giant cloud of debris and experiencing a meteor shower, the inner solar system is still peppered with random space dust and rocks. That means meteors can happen anytime. On any given night, the so-called sporadic background rate of meteors is about two to seven per hour. During meteor showers, that rate can jump, sometimes tenfold or more.

Only the big survive

Whether or not a space rock survives its fall to the ground (which is rare) depends on factors like its original size, speed, and angle of attack. Larger meteoroids that fall more directly through Earth’s atmosphere are more likely to strike the ground as meteorites. That’s because they have less distance to travel and more material to spare. Even if their outer layers burn away, some chunk of their core is likely to survive — though it’ll be much smaller than when it started its plunge.

How much smaller? According to the Planetary Science Institute, a Volkswagen Beetle-sized meteoroid would end up as a microwave oven-sized meteorite by the time it passed through the atmosphere. And a basketball-sized space rock could leave behind a softball-sized meteorite. Of course, these sizes are only applicable to meteoroids made of dense, strong material. Fluffier or more delicate space rocks would end up much smaller upon impact.

The cometary debris clouds Earth regularly flies through — like a kid running through a sprinkler stream — are made up of tiny grains of rock and dust, typically ranging in size from smaller than a grain of sand to about the size of a pea. Furthermore, meteor shower particles tend to be “fluffy,” meaning they’re not very dense and burn up easily in Earth’s atmosphere.

Most meteoroids, associated with a shower or not, also strike our atmosphere at glancing angles, causing them to simply skim through the upper layers with no chance of reaching the surface. But even if they come in at steeper angles, their tiny forms burn up completely on the way, leaving nothing left to hit the ground.

So, while meteor showers produce plenty of meteors, they do not result in meteorites. And while that might seem unfortunate, it’s certainly good news for observers — they don’t have to worry about space rocks raining down when they step outside to enjoy a beautiful light show.

This article was originally published online December 11, 2020.