The leading answers to that question have shifted over the years, driven by scientific discoveries, public curiosity, technological realities, and political agendas. For human exploration, the list of plausible destinations has always been short: Earth-orbit and the Moon. (Mars is achievable, no doubt, but we not at all technologically ready to go there right now.)

For robotic probes, the list started in the same place but kept going: inward to Mercury and the Sun itself, outward past Neptune and Pluto.

For the most part, though, we’ve ignored the other 99.9999% of the objects in the inner solar system: the asteroids. There are, by current estimates, nearly two million asteroids more than a kilometer in diameter. Collectively, they represent a landscape greater than the surface of the Moon, but we’d never seen one up close until 1991. Even now, we’ve visited just a dozen of them. The asteroids didn’t get much love.

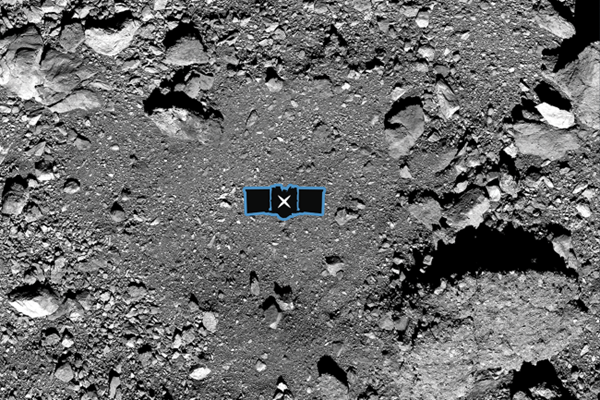

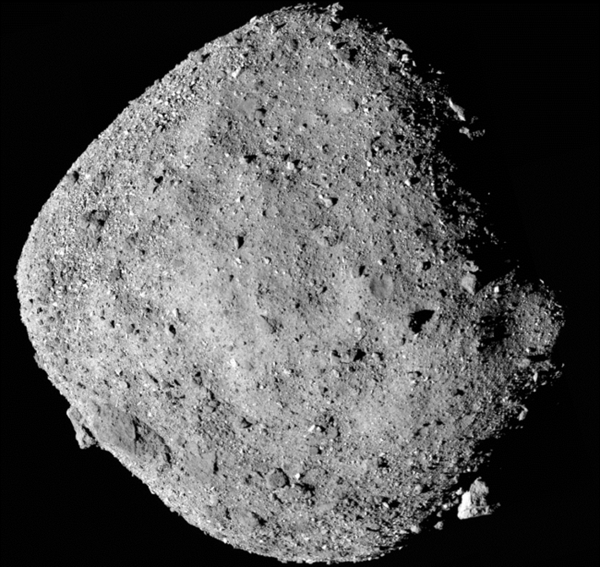

That’s about to change: There currently eight dedicated asteroid missions underway or in development (nine if you include MMX, a Japanese mission to Mars’s inner moon, Phobos, which might be a captured asteroid). Hayabusa2 is about to swing past Earth next week, dropping of samples of asteroid Ryugu over Australia. OSIRIS-REx will follow behind with a larger cache of rocks that it recently collected from another small asteroid, Bennu.

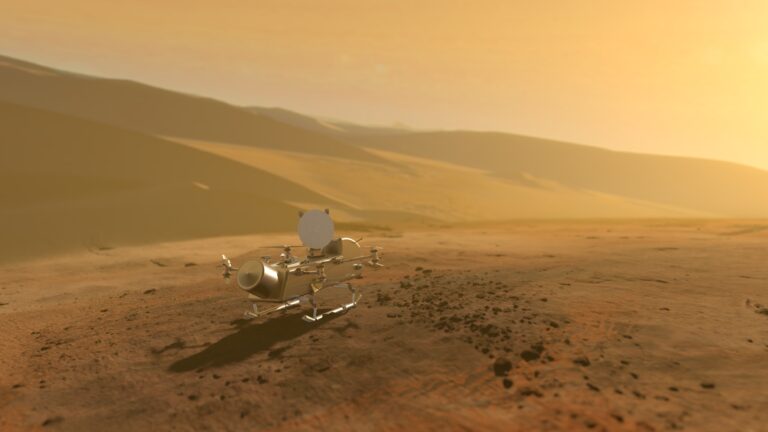

The next round of asteroid missions will try out a bunch of unusual styles of exploration. Lucy will visit the Trojan asteroids that move in the same orbit as Jupiter. The Psyche mission will travel to the asteroid Psyche—a mysterious object that appears to be composed almost entirely of metal. DESTINY+ will head to Phaethon, a “rock-comet” asteroid that appears to be crumbling because it passes so close to the Sun. NEA Scout will use a solar sail to navigate to a near-Earth asteroid.

Most dramatic of all, the DART spacecraft will ram full-speed into a small asteroid Dimorphos in 2022. The goal is to test out a technique for deflecting a dangerous asteroid if we discover one coming our way; four years later, the Hera probe will follow up to assess the damage.

The DART-Hera pair of missions embody perhaps the most compelling reason why people find asteroids so compelling. We know that small asteroids hit Earth all the time; we know that larger ones can cause significant damage when they hit; and we have the fundamental technology needed to deflect an asteroid if it were on a collision course. Understanding asteroids could therefore be a matter of life and death.

One measure of how much people are moved by the asteroid threat is the regular appearance of “killer asteroid” stories in the tabloid newspapers. A more meaningful measure is the new IMAX movie Asteroid Hunters. The COVID-19 pandemic has sharply reduced its audience for now, but when science museums and IMAX theaters safely reopen, the movie will give you a dramatic view of asteroid science—and especially of the science behind averting a natural disaster from above.

I spoke with Phil Groves, the writer/producer of Asteroid Hunters, to find out why he finds asteroids so interesting, and to understand how he worked to make the science accessible to the general public. An edited version of our conversation follows.

I grew up a hardcore NASA geek, before I made a sharp left into the film business. About 12 years ago, I ran into this article describing a proposed European Space Agency mission called Don Quixote [a predecessor to the DART/Hera missions]. It was going to send a probe to knock a binary asteroid, which is a little moon asteroid that goes around a bigger asteroid, to test the notion of asteroid deflection. The idea of protecting our planet against an asteroid this way never occurred to me until I read that article.

At the time, I was running development and global distribution for IMAX, and it struck me that this was the perfect topic for the IMAX format. From there, I began to research the topic, reaching out to NASA and JPL scientists. This film became a passion project.

I’m afraid that most people still picture the movie Armageddon when they think about protecting Earth from a hazardous asteroid.

If an asteroid is headed towards Earth, you send up a bunch of oil rig workers to go blow it up. It’s quite a misunderstanding! One, that is something you wouldn’t bother to do, sending people up there. And two, you wouldn’t want to blow up the asteroid, because then it sends a cloud of buckshot to Earth. But there’s a real problem here, and it’s a problem that is solvable. The threat of asteroids is the most preventable of all natural disasters.

To pump up the drama, some news stories hype the likelihood of an asteroid collision. A major impact is actually a very low-probability risk, but potentially a highly destructive one. How do you communicate a subtle point like that?

It’s a really good question. There are about a billion asteroids going around the sun [if you include the really small ones]. Most of them live in the asteroid belt, but there are two classes of asteroids that we pay particular attention when it comes to planetary defense. One is near-earth asteroids. Its very name tells you why we’re interested in them—because they come close. Then there’s the class of potentially hazardous asteroids, the ones that come very close to intercepting Earth in our orbital path around the Sun. About 10 percent of near-earth asteroids fall into this category.

We know of a couple thousand potentially hazardous asteroids. And here’s the part where you talk about the low probability but high consequence in the event of an asteroid strike: We’ve found only a third of these asteroids, maybe.

So we shouldn’t relax just yet?

The good news is, of the asteroids that we know about, none pose a threat except for at least 100 years or further in the future. But it’s the asteroids that we don’t know about that we have to keep on looking and finding. It’s not a question of if an asteroid will hit Earth again, but when. Look at the Moon: You see all the craters there. Well, Earth has been hit more often than the Moon has been. We just have weather and geology that erase the records.

That said, there’s about 200 impact craters that we do know about on Earth. An asteroid big enough to cause real trouble to a city or even a small country hits earth once about every 100,000 years. The next one could be 100,000 years from now, because that’s just an average obviously, or it could be tomorrow when we find an asteroid that is coming our way. We have to be ready for it. That’s what Asteroid Hunters is all about.

The way I internalize that sort of thinking is an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. You have a house. You buy a fire extinguisher, and the expense of that fire extinguisher relative to the overall cost of the house is pretty small. The amount of money that you would have to spend to send up a space telescope to look for asteroids so that we can find it before they find us, is pretty small compared to the overall economy of the world. When you go to sleep at night, you lock your front door. The chances of someone invading your house in the middle of the night is pretty minuscule as well, but you do it. This is the same thing, just on a grander scale.

And it doesn’t even cost that much! NASA’s budget for finding asteroids is probably less than what it costs to make one Hollywood asteroid-disaster movie.

That might be generous, by the way. NASA’s budget for planetary defense in this past year is about 150 million bucks. Just about every Marvel movie made out there cost more than that. And this is the only natural disaster you can actually prevent from happening. You can’t cork a volcano. You can’t throw a net over a hurricane. You can’t glue shut a fault line to stop earthquakes. But this we can stop.

What do you find most scientifically exciting about asteroids?

The coolest fact that I learned along the way [making Asteroid Hunters] is that the asteroid belt is a planet that never came to be because of this big gravitational bully called Jupiter. It jealously prevented a planet from ever taking shape because of its gravitational influences on planetesimals, which is what asteroids are. They’re the leftover materials of construction of the planets of the solar system. The big gap between Mars and Jupiter is because of Jupiter’s huge influence. It was the first planet to form, and it’s the biggest. It kept things stirred up, gravitationally speaking, in that area, so the asteroids were never given a chance to come together and form a planet.

Then over the four-and-a-half billion years, most of the asteroids have either been sent packing outside of the solar system or sent inward, where they become impactors of the Moon and the Earth, not to mention Venus, Mercury, and Mars. Some also fall into the sun. The asteroid belt today is maybe 1 percent of what it used to be. All of this stuff, it’s a big ammo belt, just being flung outward and inward over the course of the eons.

It’s an exciting time in asteroid exploration, with Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx bringing asteroid samples back to Earth. Any thoughts on these missions?

They’ll help us get an understanding of the construction of our solar system and maybe even the formation of life itself. A lot of these asteroids carry with them organic compounds. You want to know: Did they bring water to Earth and Mars and perhaps other planets?

What’s also interesting about OSIRIS-REx is the asteroid it’s investigating, Bennu, is one of these potentially hazardous asteroids I was referencing earlier. It’s going to pass close to Earth in 2035. It’s not going to hit then, but Earth’s gravity could have some influence on its orbit around the sun. After that, Bennu may become a real risk to our planet, and it’s a pretty big asteroid. It’s about 500 meters across, more than 1,500 feet.

It’s a rubble pile, and knowing that is an important aspect of planetary defense. How you would mitigate the threat could depend on your understanding of the asteroid structure. Is it mostly metallic, like a big cannon ball? Or is it a rubble pile, where if you whack it too hard, it’ll break apart? Then you’d have a pile of buckshot, which could be just as bad.

For Asteroid Hunters, you researched many different ideas about how to deflect asteroids. Which idea did you find most persuasive?

We show a couple of techniques, the gravity tracker and the kinetic impactor. But my favorite way is also the way that many scientists prefer: sending a nuke out into the path of the asteroid. A nuke is the greatest amount of energy in the smallest package.

When the nuke goes off, it irradiates the surface of the asteroid. The heat that’s reflecting off of the surface and the ablating rock create an opposing thrust, which alters the orbit of the asteroid. It’s kind of a nice one-size-fits-all. It doesn’t matter what the structure of the asteroid is like. For any internal form, it will do a great job in reflecting that heat back out.

It’s a weird time to release a movie like Asteroid Hunters, in the middle of a pandemic. What message do you want people to take away from it?

The heroes of the movie are scientists, who are using the power of science to watch our back. One of the things that’s really important in protecting our planet—not just against asteroids but against any threat, including COVID—is working together. When we are working together, there isn’t anything that we can’t defeat, including the most preventable of all natural disasters.