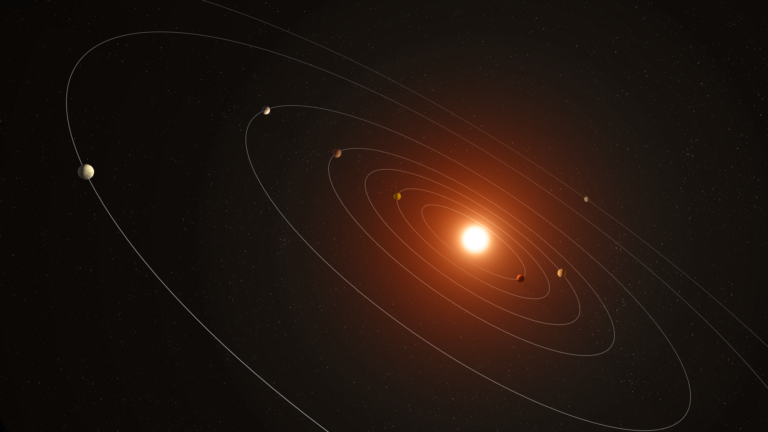

As planets form in the disks of gas and dust around young stars, their orbits sometimes fall into a kind of lockstep. Astronomers call this an orbital resonance — after a certain whole number of orbits, the planets all return to same spot relative to one another. That rhythm is held together by the small gravitational tugs the planets exert on each other. But over time, these resonances are often destroyed by planetary migration, or at least disturbed by the gravity of a passing star.

Now, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and ground-based telescopes of the European Southern Observatory have uncovered a system of at least six exoplanets, and five of them remain locked in a delicate chain of resonances: 18:9:6:4:3.

In other words, in the time it takes for the innermost planet to orbit its host star (dubbed TOI-178) 18 times, the next closest planet orbits nine times, the one inside that completes six orbits, the next planet four, and, finally, the outermost planet makes three laps.

Watch and listen for yourself with the above animation, which sets the system to musical pitches. The result is a celestial music box: Each of the five planets is assigned a note in a pentatonic scale (like the black keys on a piano) that’s played every time the planet completes one-half or a full orbit, forming more complicated chords when all the worlds line up together.